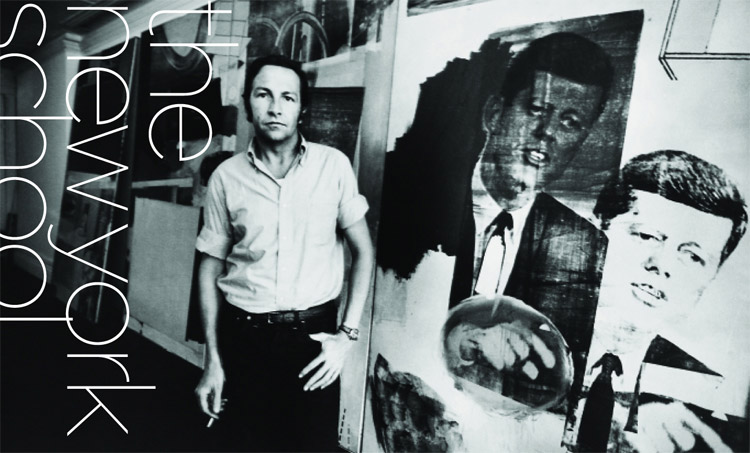

Robert Rauschenberg, in his studio in 1967, layered silk screen images of John F. Kennedy with sweeps of paint to create this seminal Pop art work.

Discarded scrap-iron was Richard Stankiewicz's preferred medium, as in the delicately balanced We two are so Alike (1958), although, noted art critic Hilton Kramer, "there's nothing at all junkie about the sculpture itself."

BOUND BY A NEIGHBORHOOD, NEW YORK ARTISTS BUILT A MOVEMENT AND A CITY BASED ON “COOL”

by Carly Berwick

In 1953, a young artist called on Willem de Kooning, then the star of the New York art world. The visitor wanted one of his drawings, he told the painter, in order to erase it as an artistic statement. To the young man's surprise, de Kooning agreed and, after much deliberation over the right piece, gave him a drawing to destroy.

In 1953, a young artist called on Willem de Kooning, then the star of the New York art world. The visitor wanted one of his drawings, he told the painter, in order to erase it as an artistic statement. To the young man's surprise, de Kooning agreed and, after much deliberation over the right piece, gave him a drawing to destroy.

The now-famous story of Robert Rauschenberg's erased de Kooning, a key early work of "pop" art, seems like a parable of generational change, fueled by Oedipal desires to do away with close influences. It also appears to neatly symbolize the dramatic shift in mid-century American art from heated, emotive abstract expressionism to cooler pop art, which put popular culture—ads, newspaper items, and comics—right into paintings and collages.

But an exhibition at NYU's Grey Art Gallery this spring makes the case that the traditional story line of the radical shift from expressionism to pop is too simple and excludes too many good artists of the period. Drawing on Grey's own collection—with many pieces donated by the artists who worked, lived, argued, and drank among the streets surrounding the gallery—the exhibit is an all-inclusive snapshot of the work produced at the time, rather than an idealized vision of art history. "Normally, these changes are seen as parental rebellion," says Pepe Karmel, the chair of NYU's art history department and curator of "New York Cool." "But it didn't happen like that; it was an evolution." In fact, many artists in the show, such as Conrad Marca-Relli, Philip Pearlstein, Louise Bourgeois (HON '05), Louise Nevelson, and Norman Bluhm, didn't neatly fit into any categorization. Living in New York mid-century, they helped form what is known simply as the New York School, which Karmel, in his catalog essay, calls the "first profoundly original movement in American art."

Woman With a Green and Beige Background, oil on paper mounted on masonite (1966), is characteristic of the fluid figuration that made Willem de Kooning a star among abstract expressionists.

Woman With a Green and Beige Background, oil on paper mounted on masonite (1966), is characteristic of the fluid figuration that made Willem de Kooning a star among abstract expressionists.

The legend of the period goes like this: Around 1930, Jackson Pollock arrived in New York from California, drank with fellow artists at the Cedar Tavern, and eventually started flinging paint on canvases he had laid on the floor. Critic Harold Rosenberg called it action painting, and the new style helped New York artists see themselves as, for the first time, superior to their European counterparts.

The other titan of the time, and Pollock's rival, was de Kooning, a Dutch immigrant who combined loose figuration with colorful abstract shapes for a new kind of abstract expressionism. Pollock's and de Kooning's New York peers included their wives, Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning, as well as Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline, and Robert Motherwell. They weren't all "action painters" or "abstract expressionists," but they lived near one another, clustered mostly around 10th Street, and Greenwich Village came to be the epicenter of the New York School.

But, as the story goes, young artists such as Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns began to reject expressionism, believing it to be overheated and self-absorbed. These artists started crafting more hard-edged, analytical objects that incorporated pieces of the growing commercial culture of magazine and television advertising. The injection of "low culture" into painting and sculpture defined the new genre of pop art, and this generation's fascination with the role of the viewer would also lead them to explore minimalism, conceptualism, and performance art.

In the process of distancing themselves from the old aesthetic, Karmel says, ideas on the art of memory also emerged. A collaboration between poet Frank O'Hara and painter Norman Bluhm is part of a section of the exhibition called "Ars Memoriae," a title Karmel invented to identify this fusion of pop art and its embrace of "low culture" with genuine emotion. Inky abstract lines on gouache paintings are punctuated by O'Hara's scrawled short poems that read: "This is the first person I ever went to bed with" or "Reaping and sowing, sowing and reaping." Karmel says, "It was a celebration of everyday life as a way of shattering pious platitudes about what aesthetic experience should be."

TOP: PEGGED AS AN ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST IN THE 1950S AND THEN AS A MINIMALIST IN THE '60S, KENNETH NOLAND IS NOW CONSIDERED ONE OF THE PREEMINENT AMERICAN COLOR FIELD PAINTERS, AS SEEN IN SPREAD, OIL ON CANVAS (1958). BOTTOM: Alex Katz's figural paintings, such as Ada Seated, oil on canvas (1963), one of many of the artist's wife, have been described as a cross between early Italian Renaissance painter Giotto and the Krazy Kat comic strip.

LEFT: Poet Frank O'Hara scribbled pithy, emotive lines amid painter Norman Bluhm's abstract blots to create a series of collaborative works, including Meet Me in the Park, gouache on paper (1960). MIDDLE: Robert Rauschenberg bridged abstract expressionism and Pop art with collages such as this 1957 untitled piece made from oil, papers, wood, and fabric on canvas to become the first American to win the grand prize at the Venice Biennale in 1964. Right: Before Ilya Bolotowsky grew into his own brand of geometric abstraction in the 1960s, many of his works, such as Large Architectural, oil on canvas (1951), nodded heavily to his Dutch mentor Piet Mondrian.

For all its rejection of things past, pop art encompassed feelings, too, despite seeming to bury them. Rauschenberg's collages, for instance, are generally seen as seminal pop art, combining commercially made objects such as tires or taxidermied animals with paint streaks and newsprint. "New York Cool," however, frames its untitled 1957 Rauschenberg collage as a sentimental journey, just as filled with personal significance as any expressionist painting.

The exhibition fits in with Karmel's long-term investigation of how art and culture in the late 1950s and early '60s was more complex than many may suspect. Far from being a time of lock-step conformity, the 1950s were full of contradictions. Scrawling gestures that made fun of dramatic emotions—in paintings such as Bluhm's or even in the shtick of borscht belt comedians—signaled an avant-garde that now defined itself outside the growing middle class, while depending on it to inspire work. High-culture art thrived on mass-culture products, like comics and cars.

In addition to "Ars Memoriae" and "Sculpture: Idols and Shrines," the exhibition has sections on artists such as James Lee Byars and Charmion von Weigand, who infused their work with mystical circles and orbs, and on artists such as Frank Stella and Agnes Martin, who used grids as a way to structure abstract paintings and drawings.

With all these disparate styles, it becomes clear that the New York School was a movement linked mainly by geography. But while the New York artists pioneered neighborhoods together, they also quickly left them as young professionals flocked in, driving up rents. As early as the 1950s, artists moved down to the then-bleak area just south of Houston Street, which they would remake into a bustling culture hub called Soho. "In Soho, as in Greenwich Village before, and Williamsburg, Brooklyn, since, artists have added 'imagination, effort, and ingenuity' to cities," writes "New York Cool" catalog essayist Alexandra Lange, "seeing possibilities for art and habitation where others didn't, and through sweat equity, scavenging, and bartering, created a new aesthetic that others with deeper pockets adopted and aped."

In the early 1960s, many of the artists in "New York Cool," including de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, and Robert Motherwell, became members of the Artist Tenants Association, a group that fired off letters to the city and media demanding that artist live-work lofts should be legal, Lange notes. Many other downtown artists immediately applied for a new "artist-in-residence" status for their Soho lofts. These eclectic figures undoubtedly changed art history, but one of the more fascinating aspects of the exhibit is its reflection on how they also changed the city itself. Today, with skyrocketing rents and artists dispersed across five boroughs, the ideal of a true Bohemian neighborhood that inspires a generation—the Greenwich Village of the '50s—is mostly reserved for nostalgia.

"New York Cool" runs from April 22 to July 19. For details, visit the Grey Art Gallery Web site at www.nyu.edu/greyart.

Photo © Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images