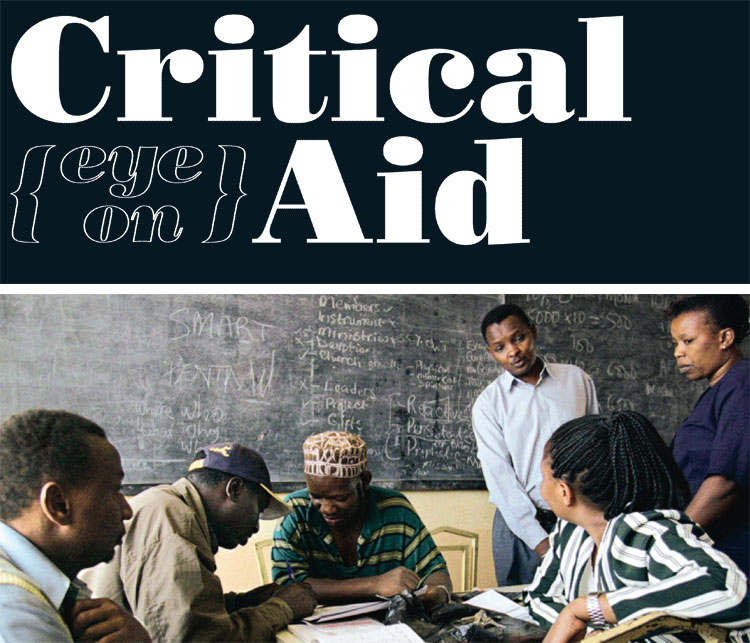

This group of tailors, food vendors, and used-clothing dealers in Kenya would never have qualified for a traditional bank loan. But they and millions of others have benefited from the rise of microfinance institutions, which grant loans as small as $50 for investment in business, health, and education.

Now more than ever, researchers are asking what it will take to fight global poverty. So far there are more questions than answers…

by Nicole Pezold / GSAS '04

On the eve of the new millennium, young Ugandans were savvier about safe sex than any generation before. They had better access to condoms, and thanks to a broad effort in the 1990s to educate the public about sexually transmitted infections, they knew how to use them. At the local store, they could even buy affordable self-treatment kits for common STIs. Only a decade or so earlier, their country had been one of the first in sub-Saharan Africa marked by the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which has orphaned more than 1.5 million Ugandan children. But in just five years, from 1993 to 1998, according to the World Health Organization, the HIV infection rate among pregnant women in some areas had dropped by more than half. International donors, in response, flooded Uganda with more money to buttress the campaign.

Then it all came crashing down.

In 2005, a whistleblower revealed that the Ugandan government unit assigned to distribute money from a primary donor, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, had misappropriated or embezzled more than $45 million. Over the next two years, after an outside audit and a judicial probe, Ugandans learned of a vast network of graft, of how money had been diverted to cover personal phone bills and buy luxury cars, and how $500,000 worth of antiretroviral drugs had expired on government clinic shelves. Blacklisted by the Global Fund, Uganda now stood to lose more than $200 million in medical aid. To add insult to injury, HIV infection was on the rise again.

The history of foreign aid is pockmarked with such stories. Almost every success is mitigated by examples of mismanagement, corruption, or incompetence—by foreign donors, recipients, or both. And yet, a growing army of governments, nonprofit agencies, and philanthropists are marshaling massive sums. The question is: Can this make a difference? There is no consensus on how exactly to "end" poverty, or what role wealthy countries should assume in the endeavor. The great stake—in lives and fortunes—has set off a war of words, sparked in part by New York Times columnist Nicholas D. Kristof, on the function of foreign aid, and its uncomfortable relationship to colonialism. There is a flurry of new—but largely untested—proposals, from ambitious programs to alleviate all the stressors of poverty at once to more piecemeal innovations that reimagine how technology might be employed to improve the lives of the poor. And while clear advances in tropical disease research and public health initiatives are saving untold lives, the debate over aid appears destined to run on. "People are skeptical of all these ideas," says Jonathan Morduch, professor of public policy and economics at the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, who notes that while new medications are scrupulously tested, most aid programs are left to chance. "Not to be too dramatic—but we're talking about people's well-being here."

On an April day in 2000, then United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan appealed to member states to take stock of an unsettling reality. "Some of us are worrying about whether the stock market will crash, or struggling to master our latest computer, while more than half our fellow men and women have much more basic worries, such as where their children's next meal is coming from," he admonished members. Answering his call, the UN declared a "Millennium Pledge" to "eradicate extreme poverty" by 2015 (as well as extend primary schooling to more boys and girls, halt the march of malaria and HIV/AIDS, and vanquish the shanty towns that ring most cities). This set off a wave of donor enthusiasm. Twenty-two nations gave a collective $104 billion in foreign aid in 2006, nearly double that given in 2002. Meanwhile, in 2004, U.S. private donations soared to $71 billion.

The need for this assistance is achingly real: An estimated 2.7 billion people—40 percent of the planet's population—live in poverty. This means they somehow scramble to feed, clothe, and shelter themselves on $2 a day or less. Within this group, 20,000 people die each day from preventable diseases and hunger. But the toll of poverty is greater: It can wreck economies and breed corruption, extremism, and violence.

Aid agencies “got away with being bureaucratic, lazy, and ineffective, when they were supposed to be dealing with the world's most tragic problems.”

—economist William Easterly

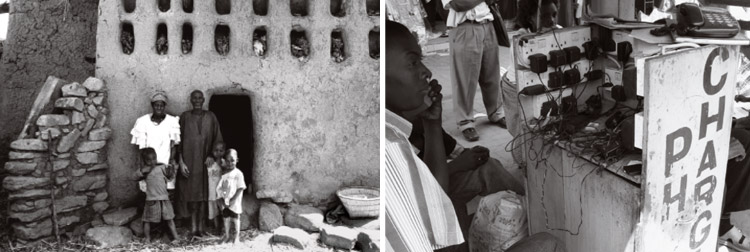

Left: Almost half the global population, including the kassogue family in northern Mali, live on $2 a day or less.

Left: Almost half the global population, including the kassogue family in northern Mali, live on $2 a day or less.Right: Juicing mobile phones is a new niche business in places plagued by unreliable power.

Foreign aid operates in the long shadow of 19th-century colonialism, when European nations took up a mission to "civilize" what they assumed were backward cultures around the world. They sliced nations in two or refashioned them with age-old enemies, excising traditional political and economic systems. This set a rickety stage for many developing countries, most of which only won independence after WWII. Many new states—despite a brief euphoria for their newfound freedom—floundered over the next few decades as they dealt with homegrown despots and corruption on one hand, and ineffectual Western aid programs on the other.

Unwittingly, many aid agencies today suffer from a lingering pretension that their "experts," armed with money and a grand plan, can resolve the problems of the poor, says William Easterly, a development economist and co- director of NYU's Development Research Institute. His own education on this topic unfolded during a 16-year tenure as a researcher at the World Bank, where he noted repeatedly—and to his employer's chagrin—how aid has failed to incite growth. He details his criticisms in The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good (Penguin). Aid agencies, he argues, are crippled by a lack of accountability to those they serve. The poor, for example, cannot vote an International Monetary Fund director out of office when a policy misses the mark. "They got away with being bureaucratic, lazy, and ineffective, when they were supposed to be dealing with the world's most tragic problems," Easterly says. He heralds instead smaller interventions that evolve organically, rely on the poor's own ingenuity and ambition, and chip away at individual problems. One well-known example is microfinance, the practice of giving incredibly small business loans—sometimes as little as $50—to poor people, which they can parlay into improving their livelihood, health, and education.

At the other end of the idea spectrum is the Millennium Villages. The program aims to remake entire communities and is the flagship enterprise of Millennium Promise, the nonprofit co-founded by famed economist Jeffrey D. Sachs to help Africa in particular rapidly decrease poverty by the Millennium Pledge's 2015 deadline. Sachs, who directs the Earth Institute at Columbia University and has advised everyone from Annan to Bono, argues in his own book, The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time (Penguin), that the extreme poor are caught in a "poverty trap." But, he insists, the West can free them with a concerted push in technology and resources, such as seed and fertilizer to improve crop yield, insecticide-treated bed nets to ward off malaria infection, and school lunch programs to both counter malnutrition and improve student performance. Since its start in 2004, the program has expanded to 80 villages in 10 countries across sub-Saharan Africa, and plans to transfer reins to local councils and government after five years.

Sachs and company are hoping that by systematically intervening, they may be better able to prescribe what it takes—in sweat and dollars—to turn a destitute village around. "Every Millennium Village starts with fact-finding and listening," says Seth Rosen (WAG '05), who raised funds for Millennium Promise for a year and has visited the experimental communities in Ethiopia and Malawi. "What happens doesn't come from a person in the West saying, 'This is what you have to do.' It's almost entirely staffed by Africans, and not just people from that particular country, but from that geographic area. That's why it's sustainable." Rosen now directs online fund-raising and organizing at Malaria No More, Millennium Promise's sister organization, whose name bespeaks its single-minded mission.

In Mali, a mother and child pose under their free insecticide-treated bed net—a cheap, effective first line of defense against malaria—courtesy of the United Nations Foundation's Nothing But Nets campaign.

In Mali, a mother and child pose under their free insecticide-treated bed net—a cheap, effective first line of defense against malaria—courtesy of the United Nations Foundation's Nothing But Nets campaign.

The academic debate spilled into public view in The New York Review of Books when Nicholas D. Kristof considered whether foreign aid can work, highlighting White Man's Burden. He noted how Easterly skewers Sachs and Millennium Promise's brand of development. Sachs quickly responded with a letter characterizing Easterly's book as a "Bah, Humbug attack on foreign aid." In reply, Easterly chastised Sachs for his "breathtaking hubris to assert that this mess can be fixed for [a] tidy sum." This claim, he asserted, "bears stronger intellectual kinship to late-night TV commercials than to African reality." Kristof, for his part, concluded, "The evidence is murky: If you take the aid data and try to correlate it to data measuring economic growth, you end up with…an unending argument."

So far, there is an incomplete picture of what interventions work and why. In the case of microfinance, a movement started in 1983 by economist Muhammad Yunus and Grameen Bank in Bangladesh—for which they jointly won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006—these small savings-and-loan institutions have generally been graded by their own advocates, and often through anecdote rather than any controlled study, says economist Morduch. To improve the quality of microfinance operations, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation granted $5 million in 2006 for the Financial Access Initiative, a consortium of development economists housed at Wagner, to tease out, for example, how incentive mechanisms work or what happens if you couple financial services with health counseling. The group, directed by Morduch with researchers from Yale and Harvard universities and the nonprofit research group Innovations for Poverty Action, is currently running 32 randomized, controlled trials in Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

Researchers are also unraveling the complexities of poverty by studying the poor themselves, whom we know surprisingly little about. With a grant from the Ford Foundation, Morduch and doctoral candidate Daryl Collins, with colleagues from Oxford and Manchester universities, are collecting the financial diaries of 250 individuals recorded over a year in South Africa, India, and Bangladesh. The results, to be published in the forthcoming 2009 book Portfolios of the Poor, show just how dynamic the financial lives of the poor really are: Even the most meager households save a portion of their earnings, which can waver from $5 one day to 50 cents the next; many rely on part-time or temporary work and a mix of formal and informal credit; some even lend to others. "It's not just about evaluating an intervention," Morduch explains. "It's a more fundamental mission to understand the nature of what it means to be disadvantaged."

One lesson that might seem self-evident is that poor people suffer from a lack of services most of us take for granted—fast cash from ATMs, a credit card for emergencies, or nearby doctors. For these issues, information technology, if reimagined, can make a difference, says Lakshminarayanan Subramanian, an assistant professor in computer science at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences and founder of the research group CATER (Cost-Effective Appropriate Technologies for Emerging Regions), with colleagues from Courant, Wagner, and the NYU School of Medicine. "You should not be thinking from the traditional mentality of having a personal computer," he says. Instead he sees cell phones—nearly ubiquitous in the developing world—as small but powerful tools for linking people in ways we're only beginning to explore. With a grant from Microsoft, Subramanian and colleagues are working with health field workers in Ghana to network BlackBerry-like smartphones to track the flow and consumption of antiretroviral drugs for HIV/AIDS.

They also recently reworked a satellite dish and a wireless card to send a Wi-Fi Internet signal more than 250 miles in Venezuela—much farther than any service in the United States. It's easily 50 times broadband and at a fraction of the cost, Subramanian says. Last year, the renowned Aravind Eye Hospitals in India used this network to remotely examine and diagnose 25,000 patients in nine rural clinics through high-quality video-conferencing. Over the next few years, the hospital will scale up to 50 clinics to "tele-treat" some 500,000 people.

All critics, including Easterly, agree that health care has undeniably benefited from more aid dollars; literally millions of lives have been saved, according to a report by the nonprofit Center for Global Development. Since 1996, routine childhood immunization has nearly eradicated measles as a cause of childhood death in seven African countries. A regional control program in West Africa has rescued 18 million children from the risk of river blindness since its launch in 1974, and a national campaign on the use of oral rehydration therapy in Egypt in the 1980s reduced infant deaths due to diarrhea, a common killer in many poor areas, by 82 percent.

One of the biggest winners from the recent injection of aid is the quest for a malaria vaccine. Karen Day, who directs the parasitology department at the NYU medical school, remembers a time not long ago when scientists had to scrounge together scant grants to research the disease, which infects more than 500 million people each year—causing at least 1 million deaths, mostly among children. As one of the most ancient diseases—at least 50,000 years old, Day says—it has the capacity to quickly mutate in response to treatments as it volleys between humans and mosquitoes. National Geographic reported that some scientists believe that of every human being who has ever lived, half of them have died from malaria. Scientists expect it is only a matter of years before the disease once again develops resistance to the current cocktail of antimalarial drugs.

Until a few decades ago, creating a malaria vaccine was an unlikely prospect. "People thought it was too complex a problem; we didn't have enough money to deal with it; we didn't have the tools," Day explains. Then in 1967, Ruth Nussenzweig, C.V. Starr Professor of Medical and Molecular Parasitology at the medical school, proved it was possible to immunize mice with irradiated malarial parasites, and in the 1980s, she, along with other NYU researchers, showed that the protein that coats the parasite could generate immunity that prevented infection. Building on Nussenzweig's work, researchers have designed a vaccine that in early clinical trials in Mozambique has protected 65 percent of children against malaria attacks. "That's pretty significant," Day says. "But it doesn't look to be long-lasting, so we have to keep boosting and boosting. And that may logistically be very expensive and difficult."

If and when researchers finally produce a viable vaccine, the next hurdle will be how to efficiently negotiate the complex maze of national health-care systems, NGOs, and aid agencies, to get it to those who need it. One response has been a proliferation of the master of public health. Since 1996, applications to schools of public health have increased by more than 50 percent, reports the Association of Schools of Public Health. NYU has carved a special niche among universities by offering the first MPH completely focused on global public health, examining everything from cervical cancer treatment in El Salvador to Iraq's mental health policies, or lack thereof. "Almost nothing—chronic diseases, infectious diseases, population control, nutrition—is purely local anymore," notes Robert Berne, senior vice president for health and professor of public policy and financial management at Wagner. "A worldwide context gives you a different perspective, which is what the health issues require." Berne and others developed the two-year Global MPH as a cooperative of the medical school, Wagner, the College of Dentistry, the Silver School of Social Work, and the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development. The first class, who themselves offer a worldly perspective with more than one-third foreign born, enter the fray when they graduate this May.

Here the Global Fund scandal in Uganda offers lessons to public health workers and anyone concerned about foreign aid. While the stain of corruption and mismanagement will not be quickly washed away, Uganda has turned a corner. The public, aided by the local press, forced the government to take the incident seriously—an unlikely prospect just 30 years ago under Idi Amin's bloody autocracy. Some officials have been sacked and others are under criminal investigation. More than $550,000 has already been recovered. "Money was lost. Careers and personal reputations may be lost," mused Justice James Ogoola as he handed his 400-page report on the scandal to the president in 2006. "But the greatest losers in this sordid story have been the people of Uganda." With their vigilant demand for accountability and action, however, they've also shown they are the greatest hope for the future.

Photo from Top: LEFT: Photo © Shawn Davis; RIGHT: Photo © AFP/Getty Images; LEFT: Photo © Atul Loke/PANOS; RIGHT: Photo © kiwanja.net; LEFT: Photo © www.nothingbutnets.net; RIGHT: AP Photo Aaron Favila

“Ours is a more fundamental mission to understand the nature of what it means to be disadvantaged.”

—economist Jonathan Morduch

NYU researchers have designed a vaccine that in early clinical trials has protected 65 percent of children against malaria attacks.