alumni profile

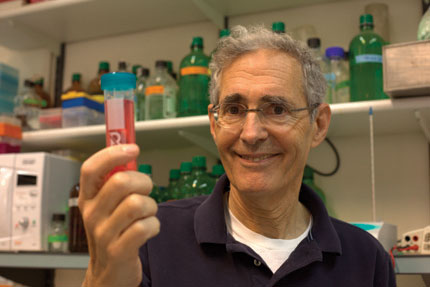

Methylation Man

Howard Cedar / MED ’70, GSAS ’70

by Kevin Fallon / CAS ’09

Howard Cedar has a philosophy when it comes to research: It’s all about the basics. “If you look under the hood of a car to see what’s wrong, looking at the surface and moving one thing or changing another may help,” he says. “But if you really understand how the car works at a basic level, you could find the problem easily.” This curiosity propelled him into the burgeoning field of cellular biochemistry and human genetics. It was the early 1970s and scientists were just learning the genetic code and developing methodologies for defining a gene and deciphering how it works in a cell. As one of the first graduates of NYU’s combined MD/PhD Medical Scientist Training Program, he started working for the U.S. Army’s Public Health Service and the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. “It was all so brand−new and exciting,” Cedar says.

Howard Cedar began his career as scientists were unraveling the genetic code. ”It was all so brand−new and exciting,” he says.

Nearly four decades later, the native New Yorker—and Harry and Helen L. Brenner Chair in Molecular Biology at the Hebrew University Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem—is gaining international recognition for pioneering research on human development and genetic expression. More specifically, he, with fellow HU professor Aharon Razin, has advanced the knowledge on DNA methylation—or the chemical changes in a DNA molecule—for which he was awarded the 2008 Wolf Prize, the Israeli version of the Nobel. The work could substantially alter how doctors approach disease treatments—and just might lead to a cure for cancer.

Every cell in the body contains the same genetic information, or operating instructions, but they must be regulated according to their different functions. DNA methylation is a form of regulation and determines when a gene is turned on or off. This ensures, as Cedar puts it, that “liver cells behave as liver cells and kidney cells as kidney cells.” When a gene methylates abnormally, it can generate cancer cells. So if researchers can find a way to inhibit the abnormality, they could alleviate certain types of cancer. Methylation may also revolutionize the way diabetes is treated and may help understand the programming of stem cells.

Cedar humbly describes his work the way someone might recite a recipe. But Andrew Chess, professor at the Center for Human Genetic Research at Massachusetts General Hospital, says it applies to the development of basically every animal and plant: “Because many human diseases, including cancer, are caused by perturbations in the readings of genes and the genome, it’s an outstanding contribution to the basic knowledge of medical science.”

While he may downplay his accomplishments, Cedar seems cognizant of his bracha vehazlaha—Hebrew for blessings and success—over the past year. In addition to winning the prestigious Wolf award, which includes a $100,000 prize, his son Joseph Cedar (TSOA ’95) wrote and directed the Israeli film Beaufort, which received a 2008 Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. And last June, Cedar welcomed his twelfth granddaughter into the family. “Even after 12,” he says, “it’s still very special.”

photo © Sasson Tiram