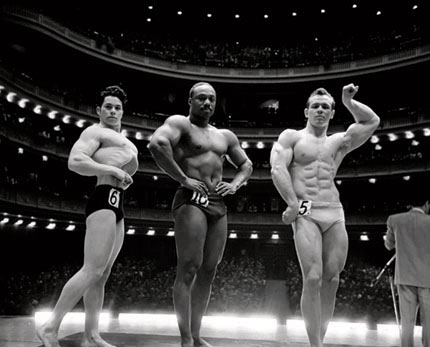

Bodybuilding was on the rise in 1949, when Burt Glinn captured this muscleman show at Carnegie Hall in New York City. Nothing said beauty and power like a sculpted chest.

by Andrea Crawford

with additional reporting by Hana Tanimura / CAS ’09

In 2001, photographer and scholar Deborah Willis was diagnosed with cancer. As she underwent chemotherapy and lost her hair, she was surprised by how people responded to her baldness in the hospital. Even in illness, she realized, beauty was significant. “People had a hard time looking at me,” recalls Willis, who was a 2000 recipient of the MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Award. “Even the people who had cancer asked the nurses to put me in a back room because I didn’t wear a wig or a hat or a scarf. That’s when I started photographing my bald head, my pitiful look, and started thinking how beauty matters.”

Since then, Willis has turned her artistic eye, scholarly research, and teaching talents to the subject. This month, the NYU University Professor and chair of the photography and imaging department at the Tisch School of the Arts publishes Posing Beauty: African American Images From the 1890s to the Present (W.W. Norton). In this follow-up to her best-selling Obama: The Historic Campaign in Photographs (Amistad), Willis has collected more than 200 images in black-and-white, color, and digital formats from some of the most famous photographers of decades past—such as Weegee, Walker Evans, Richard Avedon, Cornell Capa, Lee Friedlander, and Annie Leibovitz—along with those snapped by unknown sources.

TO DISPEL NEGATIVE STEREOTYPES, BLACK NEWSPAPERS FROM THE TURN OF THE 20TH CENTURY FREQUENTLY SPONSORED BEAUTY CONTESTS AND RAN PHOTOS OF GLAMOROUS BLACK WOMEN, SUCH AS THIS ONE BY AN UNIDENTIFIED PHOTOGRAPHER.

Even though the images are not chronological, they nevertheless trace an historic arc of how black beauty has been represented, constructed, and defined over the course of more than a century, from the end of slavery through Civil Rights and on to today. Many of these—along with additional images and videos—were featured in the recent exhibition, “Posing Beauty: The Portrait in African American Culture,” at Tisch’s Gulf + Western Gallery. The exhibit will tour until December 2011, with stops in Ontario, Los Angeles, Newark, and elsewhere.

Researched over 10 years, the book forcefully reveals the nature of beauty as, in Willis’s words, a “visual expression of power,” and demonstrates why it should be taken more seriously. At a time when one can argue that many people already take it too seriously—resulting, for example, in eating disorders and dangerous surgical procedures—Willis says this sometimes fatal drive to attain what society imposes as beauty is precisely why it needs to be studied artistically and academically. Willis, who wears bright red lipstick and nail polish, and has been told that both are inappropriate for a scholar, wants her viewers to question their assumptions about beauty. “Anyone who walks into a room has assumptions about people—assumptions based on popular culture and the media,” she says. Popular culture, parents, and even scientists try to define what beauty is—often decreeing, Willis says, that only pale skin is beautiful, that a preference for clear skin is the result of an evolutionary drive for healthy partners, or that beauty cannot exist alongside intelligence, feminism, or serious scholarship. Willis sets out to challenge such ideas.

To do so, the curator, historian, and accomplished artist delves into beauty as a symbol of power and as a force that shapes history—as it did, for example, in the 1960s and ’70s “Black Is Beautiful” movement—and as a way that people construct, shape, and alter their identities. Willis, who has spent three decades studying the portrayal of African-Americans in photography, places contemporary and historical icons alongside casual, environmental portraits of unknown subjects. Portraits of Josephine Baker, Malcolm X, Rosa Parks, Muhammad Ali, James Baldwin, Denzel Washington, Lena Horne, Miles Davis, Lil’ Kim, and Michelle Obama are interspersed among the anonymous patrons of barbershops and bars, and passers-by.

One of the earliest images is a “Runaway Slave Wanted” poster from 1863. In the notice, the woman is described as “rather good looking, with a fine set of teeth,” which Willis notes is a surprising admittance “of beauty and desire voiced in the public arena.” That this woman’s image even exists suggests that the slave owner, Louis Manigault, had her photographed to “memorialize his lover and concubine,” notes NYU historian Barbara Krauthamer.

A notably rich turning point in this history was the “New Negro” movement, which gained momentum in the early 20th century and peaked in the 1920s. Images from this time show the ways in which people, buoyed by a growing sense of race consciousness and pride, constructed their identities using refined poses, elegant clothing, or elaborate backdrops to signify their enhanced social status. Many of the subjects were among the first generation of workers after emancipation; it was an era when a number of African-American periodicals began organizing beauty contests (some of which are featured in the book) in an effort to end negative stereotypes and establish new paradigms for black beauty. “Possibly for the first time, the black press encouraged their black readers to discuss the fundamentals of what constituted black images,” Willis writes. It was in the 1920s, too, that figures such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes noted the inability of many to photographically portray African-Americans. “So few photographers know how to capture with the lens the shades and tones of the Negro skin colors, and none make of it an art,” wrote Hughes in 1928. Numerous examples from the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s are the work of two groundbreaking African-American photographers: Robert H. McNeill of Washington, D.C., and Charles “Teenie” Harris of Pittsburgh.

The act of using beauty to represent prestige or power carried through into the middle of the century. “We had our portraits made to reinforce our own stereotypes, which were positive,” explained D’Army Bailey, a judge and Civil Rights veteran from Memphis. “We saw ourselves as sharp. Our shoes were shined, our pants were pressed, and we were well presented. We had a lot of self-pride, and pictures provided an affirmation of how clean we were in our own mind. We weren’t sending messages to white people. We were sending messages to each other…for us, photography provided an extension of ourselves at our best.” The images of people in their Easter Sunday finest—taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson (Harlem, 1947), Weegee (Harlem, 1943), Russell Lee and Edwin Rosskam (both in Chicago in 1941)—are notable examples of this act of “posing” as well.

The idea culminates with the emergence of “Black Is Beautiful,” and Willis has included numerous important images from this era. One stunning example is of political activist Angela Davis in a studio image taken by Philippe Halsman, the renowned portrait photographer known for his images of Albert Einstein, John F. Kennedy, Pablo Picasso, and Marilyn Monroe. Pictures by Richard Avedon—who also trained young African-American photographers to document the activities of the Civil Rights movement—show Donyale Luna, one of the first black cover girls, in two images from the 1960s. And then moving through to the latest cultural shift signifying beauty and power, Willis includes an image of first lady Michelle Obama (the subject of the author’s next book), who “has basically changed the landscape of beauty,” she says, with her sense of style, example of motherhood, and devotion to certain causes.

Throughout her life, Willis has watched that landscape slowly give way. As the daughter of a beautician in Philadelphia, she spent many childhood hours in her mother’s shop, listening to the stories of women who came in weekly. “It gave me a sense of importance and of self-reflection,” she explains. “I remember the blue-haired ladies…how proud they felt about their selves and their identities when they walked out of there.” And she remembers the stories of these women, many of whom were domestics, “about how they were treated by their employers based on the way they presented themselves.”

While Willis knows well the power of beauty, she never sets out to define it. Despite what designers dictate through runway models or what scientists attempt to prove when a baby’s gaze lingers upon more symmetrical faces, beauty, Willis argues, cannot be defined objectively. “I know it’s corny, and my students laugh at me all the time,” she says, “but I really believe that it’s individually defined, socially defined, and—people hate for me to say this—that it’s also within.” When asked about flawless skin, she replies, “What is a flaw?” In Africa this summer, Willis was awed by women with artistic scarifications, carved into their skin when they were babies. And what about symmetry? No, she says, not for women who have survived breast cancer and have two different-size breasts.

This is why Willis emphatically states that she did not lose her beauty, or power, when she was sick and her hair fell out. Rather, she actually felt sad for the people who could not deal with their own discomfort at her less conventional appearance. “What I tried to enforce with my bald head was to get people to reflect on cultural notions of beauty, that hair is not the only appropriate way of identifying beauty,” she says.

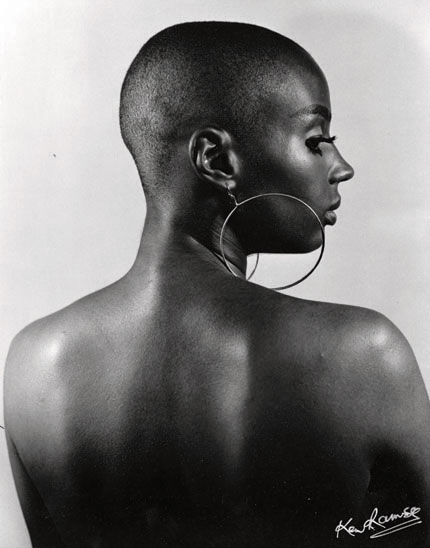

As it were, a striking image of Essence editor Susan L. Taylor—head shorn of hair—graces the book’s cover.

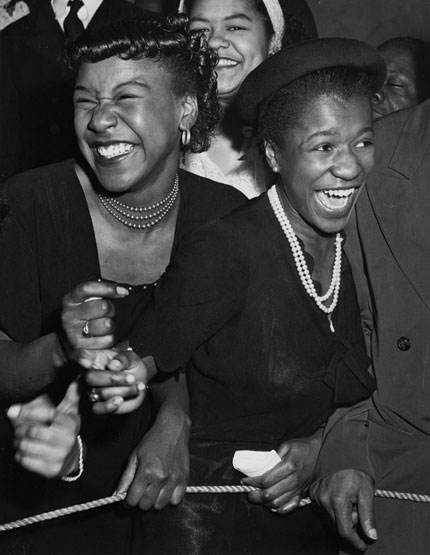

ABOVE: Weegee, aka Arthur Fellig, was one of several mid-century photographers who portrayed African-Americans dressed in their finest, whether for church or going out on the town, as in this shot from a jazz concert circa 1944. BELOW: Susan L. Taylor, the longtime editor of Essence magazine and an icon of African-American fashion and beauty, posed bald for Jamaican photographer Ken Ramsay circa 1970—the height of the “Black is Beautiful” movement.

Photos from top: © Burt Glinn; © Texas African American Photography Archive; © Weegee (Arthur Fellig)/International Center of Photography/Getty Images; courtesy the photographer Ken Ramsay

Willis forcefully reveals the nature of beauty as a “visual expression of power.”

“Our shoes were shined, our pants pressed. We had a lot of self-pride, and a picture provided an affirmation of how clean we were in our own mind.”

When asked about flawless skin, Willis replies, “What is a flaw?”