In five short years, a simple software program has revolutionized our phones—and maybe our lives

by John Bringardner / GSAS ’03

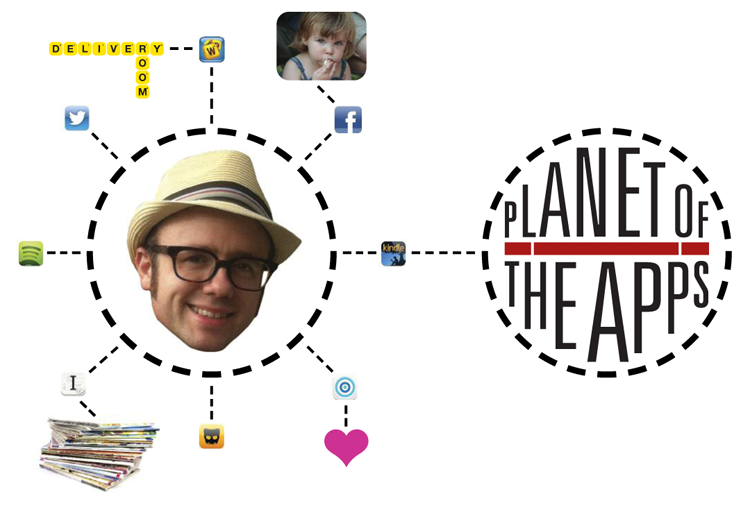

Between the moment my pregnant wife and I arrived at the hospital and the arrival of my son—a period of roughly 12 hours, only the last of which involved much participation on my part—I did many things, almost all of them on my iPhone.As the hours stretched on, I read short stories by Melville and Vonnegut (Kindle app, free). I scanned a few long magazine articles I’d bookmarked online (Instapaper, $4.99). I racked up points in a Scrabble-like game (Words With Friends, free). I surfed through countless posts on my newsfeed (Facebook, free), looking at the bons mots, dinner photos, and music choices of classmates I hadn’t seen in person for more than a decade.

I spoke with my wife from time to time, of course, but in between visits from nurses and shifting her weight in bed, she was glued to her phone too. I thought of all the stories of epic-length labors, and imagined what I would have done before my iPhone and its apps. Five years ago, I would have brought a stack of magazines and a card game with us. Fifty years ago, I would have been planted on a bar stool down the street.

The epidural went in and I began tracking the frequency and duration of my wife’s contractions (Full Term, free). But the waiting continued and I thumbed over to the App Store. I’d kept seeing an ad for an app to help me meet new “friends” (Skout, free). It seemed promising until it asked me to fill out a profile—I didn’t have time for that; I had a baby on the way. Moving on, I downloaded a similar app that had generated a fair amount of controversy but asked only for permission to access my phone’s current location. Seconds later, dozens of photo tiles revealing varying amounts of torso lined up on my screen, in order of proximity. Julio was looking for a man like me, and he was only 270 feet away (Grindr, free).

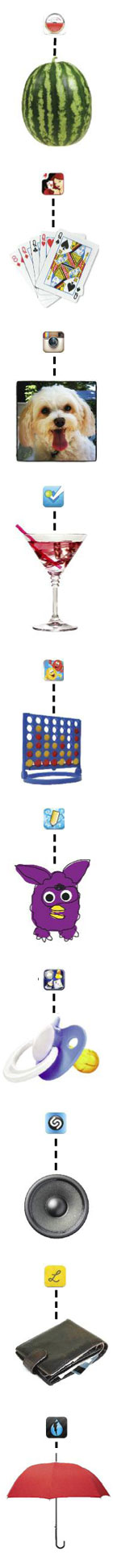

Science fiction writer William Gibson once said, “The people who invented pagers never imagined they would change the face of urban drug dealing.” Could the inventors of the smartphone have imagined Grindr, let alone Twitter, Foursquare, or the Melon Meter app, which uses your iPhone’s microphone to determine the ripeness of your watermelon?

An entire “app economy”—responsible for nearly half a million jobs in the United States—is thriving even as most industries struggle to shake off the lingering effects of the downturn.

To underestimate the degree to which apps have infiltrated and redefined what it means to use a cell phone today implies that you are quite happy to remain under that rock. Short for application, the term “app” as we now understand it originated with the introduction of the iPhone in 2007, referring to a relatively simple software program designed for mobile devices: iPhones, and eventually most smartphones, iPads, and other tablets. A recent survey by Nielsen found that one in two U.S. mobile phone subscribers uses a smartphone, and has an average of 41 apps—up from 32 last year. About 700,000 different apps are now available via iTunes alone, and Apple CEO Tim Cook said this June that the App Store has paid more than $5 billion to developers. An entire “app economy”—responsible for nearly half a million jobs in the United States, according to one recent study—is thriving even as most industries struggle to shake off the lingering effects of the downturn. These jobs ostensibly did not exist prior to 2007.

But skeptics are right to wonder what to make of it all when, in the same week that Facebook paid $1 billion for Instagram (a free, two-year-old photo-sharing app made by a company with only 13 employees), Eastman Kodak, the inventor of personal photography, was in bankruptcy court seeking to divest chunks of its nearly 125-year-old business. Is it all a magnificent bubble, or a new mobile-industrial revolution that is making our lives more entertaining, more efficient? Can life be endlessly streamlined by a smartphone with the right apps, or are these gadgets more like a Swiss Army knife with two or three useful items—a blade, a toothpick—and 78 tools for picking lint out of one’s belly button?

Apple launched its iTunes App Store in the summer of 2008, pulling together about 500 apps into a central repository in time for the launch of the second-generation iPhone. That original market did something unprecedented. In grouping under the trusted banner of Apple an assortment of software programs developed by dozens of companies most people had never heard of, the App Store helped eliminate the fear of downloading. Users could browse the offerings—in 2008, these included an alarm clock, a digital version of the game Connect Four, and A Tale of Two Cities, all for 99 cents—download and install them in a few simple steps, and know that they wouldn’t fall victim to a virus or scam and irreparably harm the $500 piece of computing equipment in their hands.

The App Store has grown in tandem with the explosion in iPhone sales. Apple sold nearly 1.4 million iPhones in 2007. In 2011, it sold 72 million, and is on track to almost double that figure this year. The company says it now receives about 800 submissions for new apps each day. Not surprisingly, video games have, from the start, been far and away the most popular. Many mirror the complex role-playing games available on an Xbox and online, but these are punctuated in the top 100 list by simpler games, such as Draw Something and Zynga Poker, the company’s top-grossing app.

But apps only percolated into ubiquity as companies outside the gaming world—media conglomerates, airlines, consumer brands—came to think that having one was as important as having a website. That shift resulted in many innovations in how we consume news and shop online, but it also saw many middling efforts by developers—or their clients—who couldn’t see the fundamental ways apps are more than simply an extension of the Internet. “Mobile devices are far more personal, and far more often with the user (almost always, in fact),” explains Clay Shirky, a professor at the Tisch School of the Arts who studies the effects of the Internet on society. “The screens are smaller, and input for creating and modifying docs is quite restricted. The whole ecosystem tends to be more tightly controlled, and tied to a payment mechanism.”

Until three or four years ago, companies would develop a Web product, then add mobile applications, says Somak Chattopadhyay, a partner at the New York-based venture capital firm Tribeca Venture Partners. Today that’s flipped—up to half of Tribeca’s investments are now in mobile, Chattopadhyay says.

“I look at my phone first thing every morning when I wake up,” Zynga’s Dan Porter says. “I almost never look at my computer.”

OMGPOP, a small online game developer based in SoHo, followed this shift. In 2008, it published an online game similar to Pictionary, called Draw My Thing. The name sounds like the kind of impish command one might hear on a playground, but it soon became the most popular of the company’s three dozen offerings. They launched a second version of the game on Facebook in early 2011, where it soon attracted about two million monthly users. But something unusual happened when OMGPOP released it as a mobile app last March, after streamlining it for a small screen, adding a memorable neologism (“Drawsome!”) as a tagline, and inventing a new name: Draw Something. Word—and, often, drawings—spread through Twitter, Facebook, newspapers, and TV news. “We knew we had a really fun game,” says Dan Porter (GSAS ’95), who, as CEO, had helped raise the $17 million in venture funding OMGPOP had almost entirely burned through at that point. “What we didn’t know was how viral it was.” Seven weeks and 50 million new downloads later, social game giant Zynga acquired OMGPOP for $210 million, largely on the basis of Draw Something’s success. A prime-time TV game show based on the app is already in the works at CBS.

If all this makes you think a new mobile era is officially upon us, you’re right. Porter, who is now vice president of general management in Zynga’s New York office, says: “As an entrepreneur, you want to attach yourself to a platform that is growing. That’s why mobile is the place to be. But usage behavior is different too, and that’s where there are also opportunities. I look at my phone first thing every morning when I wake up. I almost never look at my computer right when I wake up.”

The Big Apple isn’t the first place that comes to mind when most hear the words “tech jobs,” but that’s changing. According to a study released in February by TechNet, an advocacy group for the high-tech sector, the New York metro area is home to the biggest slice of the country’s app jobs, at 9.2 percent, beating out even San Francisco and Oakland, with 8.5 percent. The concentration of media, advertising, and finance in the city has helped draw technology companies from the Bay Area to New York’s Silicon Alley. Over the past four years, there has been a 40 percent increase in start-up funding in New York, according to Mashable, the social media news blog. Part of that growth comes from the economic implosion of 2008, which unleashed thousands of programmers formerly coding in the financial sector—long the main employer of New York’s techies. But the city has also benefitted from the explosion of consumer-focused technology that apps represent.

Foursquare (free), for one, created by Dennis Crowley (TSOA ’04) in the back of an East Village coffee shop, is frantically hiring developers after unveiling a completely redesigned app last June. An early and popular example of location-based apps, Foursquare started life as Dodgeball way back (for apps, at least) in 2005. It was Crowley’s graduate thesis project for Tisch’s Interactive Telecommunications Program and was largely designed to let you show friends how many new restaurants and bars you’d tried. With about 20 million users today, and its evolution into a broader tool for more social discovery, Foursquare’s lengthy jobs listing page includes ads specifically seeking new graduates in New York and San Francisco.

Associate professor Nathan Hull described iOS (the iPhone operating system) to me this past spring, as we toured the end-of-semester projects displayed by his students on the seventh floor of the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. The room was buzzing as graduate students in his iPhone programming course finished assembling their year-end displays—poster boards, computer screens, tchotchkes. The class, which Hull first offered in 2009, second only to Stanford, has proven extremely popular. He’s taught computer science at NYU since 1980, but Hull, whose dramatic cadence betrays his second life as a baritone and artistic director at the Amore Opera, says: “The iPhone is a great pedagogical tool. This is the most exciting class I’ve ever taught.”

The first part of the course focuses on C, one of several programming languages that can be used in creating apps for the iOS. In the second part, Hull teaches how to make storyboards in iOS. In the third part, students take what they’ve learned and build their own apps. Hull also brings in venture capitalists and assists with the sometimes confusing process of submitting an app to iTunes. NYU Mobile (free)—the university’s first official app, which helps a user navigate all things NYU—was developed by students in Hull’s course.

Calvin Hawkes (CAS ’13), a member of the wrestling team, stood beside a laptop and poster board display of his creation for the semester. The t3k.no app is a mobile version of the website he designed to help aggregate and share the latest releases in electronic music via YouTube, which has proven particularly popular for DJ mixes.

Hawkes found a hole in the otherwise crowded field of music apps. The most downloaded nongame app in the iTunes store is Pandora (free), which creates ad hoc radio stations based on the style of the song or artist name you type in. Shazam (free), an early music app, can “listen” to the music you hear on the go—in your car, in a dressing room—and, like magic, tell you what it is by comparing a snippet of the song to a central database. Newer apps from services like Rdio and Spotify allow you to listen to virtually any album ever released, for a small monthly subscription fee. But for the newest DJ tracks, which often don’t appear in typical album format, Hawkes created a way to listen to and share that music. He identified an app gap, and filled it.

A few steps away, Patrick Grennan (GAL ’12) showed off his app, which seemed so simple and useful that I had assumed, incorrectly, that it already existed. Grennan’s program allows an iPhone user to play music while recording a video. Rather than shoot a video first and use editing software to add a score later, Grennan’s app made it possible to make a music video on the fly. “What is inventing,” professor Hull asks, “but taking things that exist and putting them together?”

I recently began downloading apps that I’d previously ignored, and searching for others based on keywords, guessing that if I could think of a need, there would, as Apple used to promise, be an app for that. Foursquare, prior to its relaunch, seemed to me like something meant for people with more socially active friends—Neil is “checked into” his apartment building yet again; is he hoping one of us will call? But the new version, with smarter and more helpful lists of places to go, became a last-minute savior when friends in town for the weekend wanted to go barhopping.

More apropos to my blossoming family life, I hunted down apps for kids. On maternity leave, my wife became intimately familiar with Total Baby ($4.99), for tracking feedings, diaper changes, and the growth of our newborn. My toddler, eager for attention, struck up a daily pow-wow with Elmo, the ubiquitous red Sesame Street character, with whom she could have endless faux video phone calls that mimic the iPhone’s FaceTime feature (Elmo Calls, 99 cents).

Stuck with a broken scanner at home, I found the TurboScan app ($1.99) to take a photo of my son’s birth certificate and automatically turn it into a PDF I could e-mail. It’s not practical for scanning more than a few pages at a time, but it has already rendered my home scanner obsolete. I found apps to help me find a babysitter (Care.com, free), create a virtual wallet (Lemon, free), and watch True Blood (HBO Go, free with HBO subscription).

After talking to so many app users and developers on the crowded streets of New York, I wondered what the selection was like for smartphone users elsewhere. Turns out, even truckers with only the soft glow of a dashboard and an iPhone for company have at least a half-dozen apps showing them rest stops, Walmarts, and warehouses. And, to judge by their reviews, plenty of truckers use them. “This app has its times,” wrote Donna Hardin, about DAT Trucker Services (free), “but don’t we all.”

But it was when I downloaded Dark Sky—at $3.99, relatively expensive among weather apps—that I found myself playing the developer, thankful for the technology at hand but eagerly imagining what it could be. Dark Sky uses your phone’s location to determine the likelihood and level of rain wherever you are, for the next hour. It is shockingly accurate: “Expect light rain in 7 minutes, followed by heavy rain in 23 minutes.”

Still, with a few tweaks I could see ways to improve an app like Dark Sky, to integrate it even more into my life. If it used so-called “geofencing” technology to determine whenever I’m about to leave my apartment or office, Dark Sky could automatically send me a reminder to take an umbrella. I might proactively look out the window and check any number of websites to see the forecast, but apps are in my pocket, always with me to offer a little edge. Are they making me dumber? For now, at least, they’re keeping me drier.