Cutting-Edge Research

neural science

Beauty within the Brain

What happens in your brain when you’re moved by a work of art? That depends on the piece and the person. A new study published in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience confirms that emotional reactions to art can be highly subjective, and may reflect as much about the viewer as the canvas. “When we are moved, it’s because we feel like we are learning something about ourselves in the world,” posits Edward Vessel, a neuroscientist at NYU’s Center for Brain Imaging, who led the study along with Gabrielle Starr, acting College of Arts and Science dean and a professor of 18th-century literature, and Nava Rubin of the NYU Center for Neural Science.Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, the team took moment-to-moment snapshots of which parts of the brain were active as a person reacted to paintings. Subjects were then asked to rate those paintings on a scale of one to four—with four indicating that the work was deeply moving. The paintings were all museum quality but deliberately unfamiliar, so that notions of an artist or work would not color the participants’ ratings. Across the board, the occipitotemporal, or sensory, section of everyone’s brain was activated upon viewing the paintings. However, only when subjects rated a painting a four did a specific network of frontal and subcortical regions—areas of the brain involved with self-referential thoughts, identity, and emotional mind wandering—light up.

The novelty of this research is that it parses out the systems that react visually versus emotionally, and the findings suggest that everyone’s brain system allows them to be moved by visual art—and likely music, dance, or literature—even if we respond to different works. “The pieces of art that have the most universal appeal,” Vessel says, “are those that have layers of complexity and can resonate with people personally, regardless of who they are.”

—Naomi Howell

dentistry

Are Some Cavities Rooted in violence?

A child’s dental checkup may reveal more than just the status of his or her pearly whites. A breakthrough study at the College of Dentistry shows that verbal or physical aggression in the home can lead to an increase in childhood caries. The research, which was launched by the Family Translational Research Group within the department of cariology and comprehensive care, joins the work of psychologists Amy Smith Slep and Richard Heyman, with associate dean Mark Wolff, who were awarded $1 million by the National Institutes of Health in 2009. Heyman says, “There are two hypotheses about how oral health is affected by parental discord.” One theory is that negligent parenting, caused by conflict, results in children eating sugary foods and not brushing regularly. The other is that young children under stress have weaker immune systems.

According to Wolff, “A simple lecture on brushing isn’t going to improve things. You have to change parenting behaviors.” The team is now focusing on an intervention in the maternity wards of Stony Brook University Hospital and Bellevue Hospital Center, where they seek out newborns at high risk for caries (based on family income and education) and enroll the parents in a program that promotes conflict resolution and oral care. At 15 months, the children will receive a dental exam, which the researchers hope will shed light on the intervention’s effects and provide ideas for future prevention. Heyman notes, “[Our aim] is to lower risk factors and get messages out on good preventive health care. Not just oral health, but all health.”

—N.H.

mechanical engineering

Swimming With the Robots

Fish are the ultimate synchronized swimmers. But when one fish takes the lead, what convinces the others to follow?

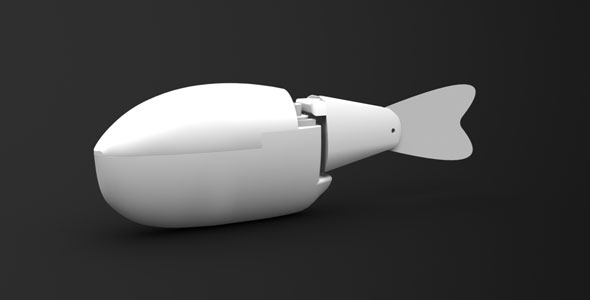

Mechanical engineer Maurizio Porfiri and his team of researchers at NYU-Poly’s Dynamical Systems Laboratory are exploring that age-old question in a new way—by building robotic fish that can infiltrate the ranks of living schools. Study of the interactions between live fish and Porfiri’s robotic imposters could unlock the mysteries of schooling—a key subject for scientists studying leadership and social behavior in the animal kingdom.

Porfiri and Stefano Marras, a researcher at the Institute for Coastal Marine Environment in Italy, built a robot that mimics the back-and-forth tail movement of a real fish. The white plastic- covered contraption—twice the size of the golden shiner it’s meant to imitate—isn’t much to look at, but in this case, it’s realistic movement that counts. A battery inside the robot sends a current to the flexible back end, causing the tail to bend just like the muscles in a real shiner.

In one experiment, Porfiri’s team placed individual golden shiners into a water tunnel and found that when the robot beat its tail at a certain frequency, 60 to 70 percent of the fish fell in line behind it, as though in a school. The results, featured in a cover story last February in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, suggest that one reason fish school is to save energy. Swimming behind a leader offers a hydrodynamic advantage similar to the aerodynamic one that a bicyclist enjoys when drafting closely behind another rider.

In a subsequent study, Porfiri created a colorful robot designed to catch the eye of the visually oriented zebrafish. Shaped like a plump, fertile female and painted with the species’ characteristic blue stripes, it attracted followers as long as the lights were on. In the dark, the zebrafish were scared off by the robot’s noise. Future studies aim to create a robot fish that flaps its tail silently.

Before the robot fish join schools on the open seas, they’ll also need longer-lasting batteries, the ability to dive deep into the water and swim against currents, and artificial intelligence, which will allow them to respond to the movements of living fish. Porfiri hopes his robots will someday act as aquatic “sheepdogs.” “If you have pollution or some other major problem,” he says, “it would be nice to be able to guide a group of fish away.”

—Eileen Reynolds

nursing

Clinical Trials and Tribulations

For people living with HIV/AIDS, being selected for a clinical trial can be like scoring a VIP pass. Suddenly one has access to the nation’s leading experts on the disease and the latest medical treatment. But participation in clinical trials among HIV-positive African-Americans and Latinos has historically lagged behind that of white patients, which not only means they miss out on care, but also presents a problem for researchers seeking to understand the effects of new medications on diverse groups.

Marya V. Gwadz and Noelle R. Leonard, senior research scientists at the NYU College of Nursing, set out to identify intervention strategies to address that ethnic disparity. Between 2008 and 2010, they recruited 540 HIV-positive New Yorkers for the ACT2 Project, a peer-driven intervention in which the African-American and Latino participants, in a series of interactive small-group sessions, learned about AIDS clinical trials (ACTs) and discussed possible obstacles to participation among people of color. “A lot of assumptions that have been made—that people of color aren’t interested in clinical trials—are not borne out when they’re asked,” Gwadz says. After the program ended, the participants received support for navigating the clinical trials system and were allowed to recruit up to three peers for ACT2.

ACT2 participants were 30 times more likely than a control group to sign up for screening for clinical trials. Of those who were screened, about half were found eligible for studies, and nine out of 10 of those enrolled. “These are huge effects for behavioral intervention,” Gwadz says. She described one skeptical participant who arrived at the first session and declared, “I’d rather die than be a lab rat.” By the end of the study, he volunteered to get screened.

—E.R.