Johannes Vermeer meets Edward Hopper in the art of Max Ferguson

by Megan Doll / GSAS ’08

At the age of 19, fresh from a year abroad in Amsterdam, fledgling artist Max Ferguson (STEINHARDT ’80) knocked on the office door of renowned art history scholar H.W. Janson to solicit Janson’s opinion of his work.“Are you incredibly busy?” Ferguson asked the professor, whose seminal textbook, History of Art, has sold more than four million copies.

“No, just credibly,” Janson replied, admitting Ferguson into his small office at 100 Washington Square East. An awestruck Ferguson took out a selection of artwork, and immediately Janson offered to purchase one—a small painting of a young man overlooking the sea in Italy—for his personal collection.

This auspicious early transaction established a friendship between scholar and artist that lasted until Janson’s death in 1982. It also helped launch Ferguson, now 51, on a path that has placed his work in such prominent collections as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New York Public Library, and the British Museum. Ferguson’s exhibition at New York’s Gallery Henoch last fall, his first solo show in five years, drew nearly 1,000 people on its opening night, an event that, appropriately, was catered by Katz’s Delicatessen, a recurring motif in Ferguson’s work. For its three-week duration, the exhibition drew a range of viewers, from New York Times art critic Roberta Smith to rock star Jon Bon Jovi.

Ferguson, who grew up in Woodmere, Long Island, and now divides his time between New York City and Jerusalem, began his undergraduate career as a filmmaker, studying animation in the era before computer-aided design. The thousands of drawings that animation used to require honed his skills but dampened his enthusiasm for the craft. Ferguson’s eye was already turning toward the fine arts before his year abroad, but his time spent at Amsterdam’s Gerrit Rietveld Academie, where he was free to venture outside of his specialization, confirmed the shift. While there, Ferguson sold his first painting to the city of Amsterdam in an open call for submissions.

Profoundly influenced by the 17th-century Dutch masters, Ferguson describes his aesthetic as a union between Johannes Vermeer and American realist Edward Hopper. Although he prefers to work from life, most of his paintings are based on photographic studies. From these, Ferguson draws a cartoon and later transfers the lines onto a panel. Once the contours are laid, he builds up the painting with multiple layers of pigment: a monochromatic underpainting, a color underpainting, and one or two finishing layers. “The reason why a lot of contemporary artists don’t have the same richness of tone that the Old Masters have is because it’s usually just one or two layers of paint,” he explains. “The more layers, the richer things get.”

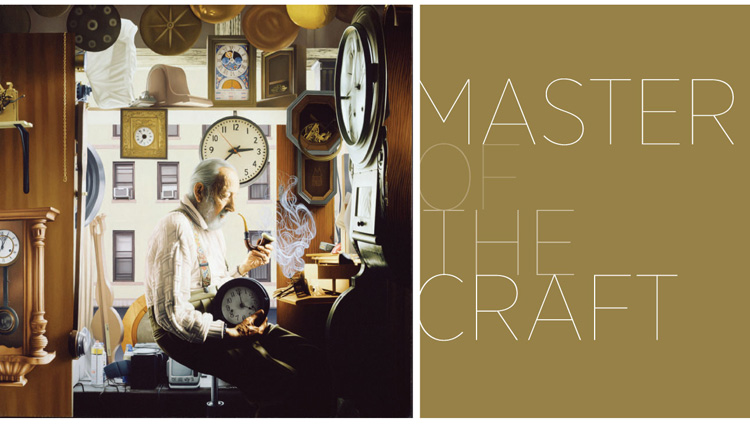

While Ferguson’s style hasn’t changed dramatically over his three-decade career, his palette has broadened from six pigments to 12, and the level of detail has intensified. His recent work Interiors (2009), a large domestic self-portrait, took eight months to complete. The Hopperesque aspects of Ferguson’s work are manifest in his subject matter—lyrical urban spaces often populated by a lone figure. Shopkeepers, craftsmen, and workers abound, and the artist is particularly drawn to older models. “I think they often have the most interesting faces,” he says. An exhibition featuring Ferguson’s favorite older model, his late father, is slated to appear in spring 2012 under the auspices of the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion Museum, near Washington Square.

Ferguson’s figures are free, however, from the anxiety and alienation typically associated with Hopper’s subjects. “They have an introspection…they are absorbed in the minute concentration of their craft and trade,” explains Laura Kruger, a curator at the Jewish Institute of Religion Museum. “No work is demeaning; no work is valueless. I think he equates how difficult it is for him to make these paintings of such intensity with the concentration of the subjects he chooses.” The artist admits to a certain identification with his subjects. “If there is one holdover from my college days, it’s this idea of repairing things, of leaving the world a little better than you found it,” he says.

It’s the especially sympathetic depictions of his subjects that have struck a chord with his admirers. Lawrence Van Gelder, retired senior editor of The New York Times Arts & Leisure section, was initially attracted to Ferguson’s subject matter—the neighborhood barbershops, doll hospitals, and clock repair shops that seem destined to vanish from New York City’s sidewalks. Indeed, there is a conservationist streak in Ferguson’s work, from the endangered urban sites that he captures down to his preoccupation with the preservation of his paintings. “In time, I came to appreciate his deep empathy for his human subjects,” Van Gelder says, “his ability to convey a sense of their inner life as well as the profound mystery of the part of them that remains unknowable.”

It is this empathy that sets Ferguson apart from other artists who paint in a hyperrealist style and whose impact hinges upon virtuosity, Kruger argues. “Max’s work is not a trick,” she says. “It’s a God-given gift. Max isn’t looking to dazzle you; Max is looking to get the most out of the people he’s portraying.” And while Ferguson rejects the photorealist label that viewers often apply to his work—a degree of interpretation and mediation goes into his paintings—his panels evince remarkable verisimilitude. “When people see Max’s work, they’re in disbelief,” Kruger adds, “so they get really close to see. People don’t just walk by.”

“Max isn't looking to dazzle you: Max is looking to get the most out of the people he's portraying.”