Cutting-Edge Research

sociology

Mapping the Effects of Violence

It has long been known that violence in children’s lives affects their cognitive development. But a violent crime in the neighborhood—even if it occurs many blocks away, and even if a child doesn’t know the victim—has a direct impact on their ability to function, according to Patrick Sharkey, whose research was published last summer in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sharkey, an assistant professor of sociology, analyzed the effects of local homicides on the test scores of African-American children in Chicago and found that living close to the location of a murder is enough to impair a child’s performance on assessments of cognitive skill. To isolate the impact of specific incidents of violence, he compared the scores of children living within the same neighborhoods who, by chance, were assessed before or after local homicides. Extreme incidents of violence cause children to perform substantially worse, he says. “The results imply that children in the most violent neighborhoods of Chicago spend roughly one week out of every month functioning at a low level.”

Sharkey mapped the location of the more than 6,000 murders reported in Chicago between 1995 and 2002, and then analyzed the cognitive test scores from two surveys of children 5 to 17 years old who lived across the city’s neighborhoods. He discovered that the closer the violent event was to the testing date, the worse the student’s performance, regardless of whether the child had a direct relationship to the victim. Effects were strongest—and children’s performance poorest—when the murder occurred within six to 10 blocks of a child’s home, but effects were present when violence occurred farther away as well. “Most of the research that’s been put forth makes the assumption that children have to actually witness a violent event in order for them to be affected,” Sharkey says. “This research is saying that it may be a broader group of children who are in need of resources and support in the aftermath of violence.”

Since the study’s publication, police officers and teachers alike have approached Sharkey, telling him that his work confirmed what they already suspected to be true. But the professor adds: “There are a lot of skeptics as well who look at gaps in cognitive test scores and assume that those gaps are due to underlying differences in innate ability or genetics, and have a hard time believing that environmental factors play a role in producing these gaps in achievement.”

In what Sharkey notes is still “a puzzle,” however, the study found that Latino students living in close proximity to a homicide didn’t show diminished academic performance. A possible explanation might be that African-American children experienced especially adverse reactions because the victims in Chicago were predominantly black. “Identifying with a victim may have more of an impact on a child,” Sharkey says. He hopes that a similar study mapping homicides and standardized testing in New York City public schools will shed more light.

—Assia Boundaoui

immunology

Keeping the Peace

Immune cells are divided into two types of T cells: the aggressors that fight infections, and the peacekeepers that monitor the fighters and prevent them from causing harm to healthy tissues. People with rheumatoid arthritis have normal numbers of both, but their peacekeeping cells are inactive and allow the aggressive ones to wrongly attack healthy tissue. Boosting the activity of these peacekeeper or regulatory cells could hold the key to developing new treatment methods for diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Michael Dustin, professor of immunology and pathology at NYU Langone Medical Center, has identified one potential target. “The protein kinase C theta enzyme is a lynchpin,” he says. “It is present in both the aggressive and peacekeeping cells. When it is ‘on’ in both cells, you have a strong immune response and when it is ‘off’ in both cells, you have a weaker immune response.”

By blocking this enzyme, Dustin and his team, whose findings were published last spring in Science, discovered a molecule that boosted the activity of the regulatory cells. In addition to treating autoimmune diseases, this inhibitor molecule could also play a role in preventing tissue rejection following transplants. “Currently the best therapy for people with rheumatoid arthritis is a protein that is expensive and has to be injected with a syringe,” Dustin explains. “An enzyme inhibitor is a small molecule, so it could be a pill. It could be as convenient as aspirin.”

—Sally Lauckner

cardiology

Heart of the Matter

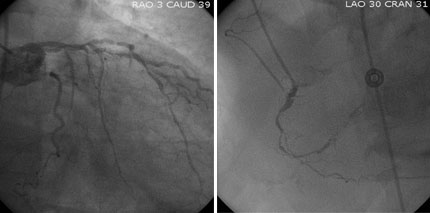

When patients develop symptoms of heart problems, one of the first things physicians test for is Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), the buildup of plaque commonly found in those who have reduced heart pump function yet no history of cardiac arrest.

But to diagnose CAD, patients have traditionally needed to undergo an angiography, a surgical procedure that runs catheters and wires from the arteries in the legs into the heart. Harmony Reynolds (WSUC ’93, MED ’97), an assistant professor in cardiology at NYU Langone Medical Center, aimed to change that. “Testing for CAD is expensive and invasive, and we wanted to simplify the whole procedure,” she says. Moreover, for many patients it’s often unnecessary, as one-third of those who undergo angiography are found not to have CAD.

Reynolds and her colleagues believed a simple carotid artery ultrasound could be an effective screening tool. Like the more invasive test, it can capture images of plaque buildup in the arteries. And because previous research has shown plaque usually accumulates in all arteries, they looked at arteries in the neck.

Since testing the ultrasound with patients already scheduled for a coronary angiography, they showed 98 percent effectiveness in preliminary diagnosis. “Most importantly,” Reynolds says, “we’re now able to rule out the need for surgery associated with the angiography.” After their findings were published last summer in the American Heart Journal, other hospitals followed suit in adopting the ultrasound testing, a procedure that almost every health-care facility has the means to perform.

—Emily Nonko

neurology

The Science of listening

Why do listeners respond better to a Bach composition than to a toddler banging on piano keys? Is it innate, wondered Josh McDermott, a researcher at the Center for Neural Science, or are humans influenced by exposure to Western music? According to his study, published last summer in Current Biology, the human ear has indeed been conditioned—but it’s the general acoustic property of harmony, and not the chords per se, that listeners have been taught to like.

“We’ve wondered since the time of the ancient Greeks why certain combinations of music sound good to people and others just don’t,” McDermott says. To help answer this, he asked 250 subjects to rate musical chords and nonmusical sounds. By isolating beating rhythms—beats that characterize dissonant chords—from the harmonic relationships believed to underlie consonance, he determined that those consonant chords give pleasure because they sound more like a single note. And this harmonic preference correlated with a listener’s musical experience: the greater their exposure to music, the more they preferred harmonic sounds.

McDermott has now turned his ear to something he calls the Cocktail Party Problem. “In crowded, noisy rooms, most of us are able to focus and hear one thing in particular,” he says. “A computer speech-recognition program can’t do this. Why can we?”

If McDermott can understand how the brain discerns one specific voice in a loud crowd, he could build algorithms to imitate it, which could allow hearing aids—now mostly useless in noisy rooms—to focus on specific sounds, as the human ear does. “This type of hearing aid will definitely happen in my lifetime,” McDermott says.

—E.N.