art conservation

It’s Not Easy Being Green

Museum conservators weigh the balance of how to protect the environment—and the art

by Rachel Wolff

Come summertime, there are at least two venues you can rely on for a constant stream of unnaturally cool air: movie theaters and museums. But that might not always be the case. Under pressure to reduce expenses as well as carbon footprints, many institutions, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, are going the now familiar “green.”

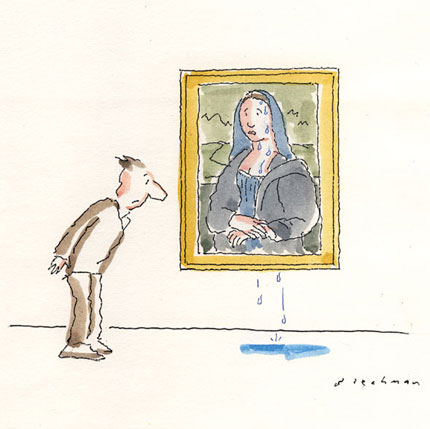

But what does a museum’s quest for reduced energy consumption mean for the precious objects within its walls? Hot lights and changes in air-conditioning can cause irreversible damage to art and artifacts. Take a painting on a wooden panel, for instance. Severe fluctuations in heat and humidity cause tension between the paint and the wood underneath, which can cause the paint to crack and flake. It’s a serious threat: So much that precious works, such as Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, are even furnished with little sensors in the back that monitor every movement, every “breath” in the wood.

As a result, it’s becoming the job of conservators—mostly known for their ability to safely touch up old paintings and mend fractured urns—to find ways to save energy, and cash, without putting cultural patrimony at risk. “The role of conservators is going to increase in the future,” says Hannelore Roemich, acting chairman of the Conservation Center at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts. The center, which celebrated its 50th anniversary last fall, recently received a $190,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to study sustainability in cultural heritage. “And when it comes to these issues,” Roemich adds, “it will be up to them to give the final okay.”

In terms of air quality and environment, museums have long heeded the guidelines established in 1978 by the International Group of Organizers of Large-scale Exhibitions (of which many major museums are members). They were costly but effective measures that allowed for little fluctuation in temperature and percent of relative humidity. But last April, under pressure from museum directors facing new budgetary restrictions and skyrocketing energy costs, the organization presented new, more eco-friendly guidelines—raising the temperature range from 67–73 degrees Fahrenheit to 59–77 degrees. The range of relative humidity also rose to between 40–60 percent, up from 45–55 percent. The wider ranges were based, in part, on the argument that the original standards were overly cautious and, in this day and age, unrealistic.

Although conservation is a science, Roemich says, it’s not always an exact one, and these new guidelines still need to be thoroughly tested. “About 90 percent of the items in a collection should be safe,” she adds, but it’s the other 10 percent (objects made of especially sensitive materials such as wood, ivory, and ceramics) that conservators must monitor more carefully than ever. Some professionals are worried. “We determined that that wider range is okay now, but what if it’s not okay down the road? There’s no going back,” says Steven Weintraub (GSAS ’75), an IFA grad and conservation consultant who worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Getty Conservation Institute before establishing his own New York advisory group, Art Preservation Services.

Without the guidance of a trained conservator, he says, museums might rely too heavily on the new guidelines and opt for cheap climate-control systems incapable of refinements. “To me, intelligent decision-making is spending the money upfront to have a flexible system so you can work to find that sweet spot that gives you the best energy benefit without compromising your collection,” Weintraub says. He also worries that as more museums seek LEED certification—the environment design standards that are a major marketing boon these days—the sacrifices could be even more extreme.

Reduced lighting is another energy-saver, but one where museums and conservators tend to see things a bit more eye-to-eye. While it’s yet to be determined whether or not eco-friendly LED bulbs are the safest and most efficient way to go, occupancy-controlled lighting—those little sensors that turn the lights on and off as you enter and leave the room—has proven to be a win-win, a way to both save energy and reduce artworks’ exposure to light. Natural lighting, however, is a different story. It might be good for a museum’s LEED campaign (and a star architect’s airy, statement-making design), but sunlight has ultimately proved more hazardous to artworks than any known artificial source.

The American Institute for Conservation is considering many of these issues. Its recently formed Committee on Sustainable Conservation Practice seeks to raise awareness of how eco-friendly concessions will affect the field. “Our big push right now is to get the information out there,” says Sarah Nunberg (GSAS ’96), an IFA graduate and Brooklyn-based independent objects conservator, who co-chairs the AIC Committee. “We don’t have the full picture yet about what more relaxed standards will do to the art, but we have to realize that the original standards are very expensive and very difficult to maintain.”

“We don’t have the full picture yet about what more relaxed standards [for temperature and humidity] will do to the art,” conservator Sarah Nunberg says.