memoir

Talk of the Town

A former receptionist reflects on life at The New Yorker

by Andrea Crawford

In 1957, when Janet Groth walked into the offices of The New Yorker magazine on West 43rd Street for the first time, she was a 19-year-old, Iowa-born, Minnesota-bred college graduate with literary ambitions. During her interview—with no less an interlocutor than E.B. White himself—she said that she wanted “to write, of course, but would be glad to do anything in the publishing field.” The magazine granted that meager wish by installing Groth at the reception desk, where she stayed for the next two decades.

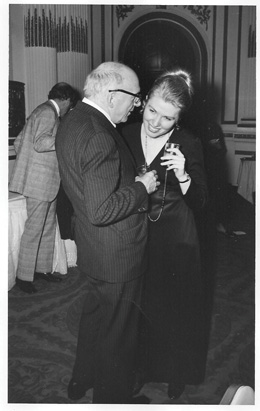

The position gave her an uncommon vantage on the lives of the legendary figures she encountered during that time. Now Groth (GSAS ’68, ’82) has gathered her stories into a new book, The Receptionist: An Education at The New Yorker (Algonquin), published last summer and to be released in paperback in June. With graceful prose and rich details gleaned from years of copious journal keeping, she writes of attending cocktail parties with “a crowd that had learned to drink in the twenties and…was hard at it still”—and, at one such occasion, of being subjected to the infamous scorn of Dorothy Parker. She modeled for Arthur Getz (who used her likeness in one of his New Yorker cover illustrations), shared “stiff Manhattans” with Pauline Kael, gave directions to Woody Allen who was always getting off on the wrong floor, and dyed Easter eggs with Calvin Trillin’s daughters. But Groth also turns a critical but kind eye upon her youthful struggles, grappling with her own reticence, personal missteps, and the “shame of the writer who doesn’t write.”

The reaction from the crowd to which she once aspired has been celebratory: The New York Times covered her book launch last summer, a packed affair at the National Arts Club on Gramercy Park. Writers Trillin, Rebecca Mead, and Mark Singer of The New Yorker have interviewed her at events in bookstores and libraries around New York City. Garrison Keillor appeared with her in St. Paul, Minnesota, calling the memoir the best of an impressive lot of such books.

Groth turns a critical but kind eye upon her youthful struggles, grappling with her own reticence, missteps, and the “shame of the writer who doesn’t write.”

“It really does feel like some kind of validation, some late graduation from something or other into—well, I’m terribly afraid there’s no place else to go except the angelic choir,” says Groth, from her Upper East Side studio apartment. On this particular day, she was surrounded by flowers that had arrived for her 76th birthday. She spoke with the husky voice of a mid-century film siren, laughing often at herself.

That same warmth and humor is well on display in her memoir, when she tells of the poet John Berryman proposing marriage and of how she lost both her heart and virginity to an unnamed New Yorker cartoonist who misled her about marital intent. In one highly evocative chapter, Groth details her “innocent yet not quite innocent” relationship with the writer Joseph Mitchell, whose acquaintance began one evening on the F train, when she was headed to a graduate seminar on Elizabethan lyric at NYU and he to his Greenwich Village home. Soon thereafter the two forged an intimate connection, sharing lines from James Joyce’s story “The Dead” over drinks at a writers’ hangout called Costello’s. From 1972 until 1978, Mitchell took her to lunch every week, typically on Fridays, where they often discussed his writing—a significant topic in these years when he struggled with writer’s block and published nothing. But the relationship, launched over Joyce, would ultimately end, its demise foretold in a disagreement over E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime, which she liked and he did not.

While full of such anecdotes, Groth’s memoir is also a forthright appraisal of young ambition, pretense, and disappointment. Groth aspired to but never got to write for the magazine. After a year and a half behind the receptionist’s desk, she received a promotion as an assistant in the art department, following in the footsteps of Truman Capote. But the promotion, her last, was short-lived. Upon returning from a vacation, six months into the job, she abruptly found herself back at reception. The art director never warmed to her, she knew at the time; only later did she realize her lack of success might also have had to do with the unexpected return of a former favored assistant, “a woman I shall call Brenda, who…thought nothing of going to bed with the boss,” Groth writes.

A measure of melancholy as well as mature acceptance and gratitude pervades the text. Yet redemption, both personal and professional, did come for Groth—and long before publication of this memoir. She left The New Yorker in 1978 to start what would become a successful academic career. While at the magazine, she had pursued a doctorate in English literature at NYU, a degree that required 15 years to complete as she took one class at a time. A professor emeritus at SUNY Plattsburg, Groth has authored or co-authored four previous books, including an award-winning critical assessment of Edmund Wilson. Academic life brought its own challenges, but she avers, “There’s nothing more noble, more wonderful, and more rewarding than a professorial career.”

Nevertheless, the publication of her first nonacademic book has been heralded as a late-in-life literary debut. And Groth has found such delight in her newfound celebrity that the angelic choir may just have to wait. She hints that a sequel to The Receptionist, taking readers beyond her New Yorker years, may well be on the horizon.