collection

Found in Translation

A new series brings the Arabic classics to English readers

by Eileen Reynolds / GSAS ’11

“And nearness brings no boredom to my longing, / nor does the love for her leave me when she has left,” an anguished poet declares. “She is my cure and sickness, and her memory my care; / but for the painful distance, passion dies.”

Oh, woe is he!

The poet’s affliction is a familiar one, but his identity—to English readers, at least—might come as a surprise. He was not a chivalrous Arthurian knight or lovesick Elizabethan dandy, but rather the 8th-century bard Dhu l-Rummah, considered by Arabic scholars to be the last of the great Islamic Bedouin desert poets. Reflecting on tribal politics, the rigors of desert life, and, of course, the agonies of love, Dhu l-Rummah and his predecessors—beginning in the 6th century, with an oral tradition stretching back even earlier—developed a system of meter and rhyme as complex as anything within the European literary canon.

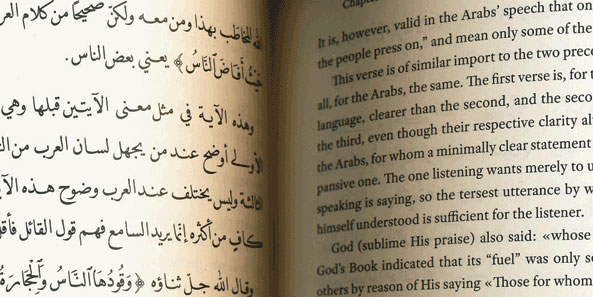

But owing to the difficulty of translation, this poetry has remained, like most premodern Arabic works, virtually unknown to English readers. For the nonfluent, fleeting encounters with Arabic literature have historically come in the form of translations of the Koran or, perhaps, hackneyed adaptations of stories from One Thousand and One Nights. But these small tastes are hardly representative of a rich literary tradition that includes everything from theological treatises to ribald tales. Now, a group of scholars led by Philip F. Kennedy, associate professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic studies, has set out to fill that gap by building a comprehensive library of classical Arabic works. The Library of Arabic Literature (LAL)—an NYU Abu Dhabi Intitute project—will present some 35 volumes ranging from pre-Islamic poetry to a 19th-century proto-novel with Arabic alongside the English translation on facing pages.

Producing new editions involves the painstaking work of tracking down and studying original manuscripts.

The first book in the series, an anthology of classic works selected and translated by University of Oxford Arabic professor emeritus Geert Jan van Gelder, was released in December. Two others—A Treasury of Virtues, a collection of sayings and teachings attributed to ’Ali ibn Abi Talib, cousin and son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad, and 9th-century legal scholar Muhammad ibn Idris al-Shafi’i’s The Epistle on Legal Theory, believed to be the oldest surviving document on Islamic jurisprudence—followed in February. “Part of our aim for the series is to publish broadly in the various different fields that constitute Arabic heritage: literature, belles lettres, law, history, biography, travel literature, geographical literature, theology—a broad array of what was written back in the premodern era,” says Chip Rossetti, managing editor of the series, which is being published by NYU Press.

The series may be read as a response in part to a recent uptick in interest among English readers, post-9/11, in the language and culture of the Arabic world. Kennedy and Rossetti envision that one day it may serve as a kind of Arabic analogue to Harvard University Press’s renowned Loeb Classical Library of Greek and Latin literature—the idea being that future generations of English readers will now be able to study the Arabic classics alongside Homer and Cicero.

The first offering, van Gelder’s anthology, Classical Arabic Literature, provides a sampling of the wide array of themes and genres that will be covered in the larger series, including wine poems, popular science, and even erotica. Though the authors of the pieces in the anthology lived hundreds of years ago, Rossetti notes that their chosen “topics are also very recognizable: love, petty annoyances, human relations.”

Some of the works, such as Egyptian writer Ahmad al-Tifashi’s “The Young Girl and the Dough Kneader,” which van Gelder describes as a “moderately pornographic” story designed to “simulate the girl’s breathless monologue,” will no doubt raise eyebrows—which the editors paused to consider. “Some readers might prefer not to encounter the bawdy and erotic in a representation of Arabic literature,” Kennedy says. “We just want, and feel obligated, to be honest.”

Because most of the works to be included in the LAL series date from before the dawn of printing in Arabic, producing new editions involves the painstaking work of tracking down and studying original manuscripts. An eight-member editorial board of Arabic and Islamic studies scholars from various universities meets twice a year to oversee the selection, editing, and translation of these texts. Some stories might seem familiar: “A Visit to Heaven and Hell,” an excerpt from the satirical The Epistle of Forgiveness by 11th-century writer Abu l-’Ala’ al-Ma’arri, is considered by some as a forerunner to Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Al-Ma’arri’s work has contemporary resonance as well. The writer’s Syrian homeland has been in the news a lot lately. “We hear about the Arab Spring, but it’s important to balance political news with more of this,” Kennedy says. That’s not to say that Arabic literature can provide easy answers to thorny 21st-century questions about power and peace. Rossetti warns against the tendency to “read Arabic as sort of a sociological text—as something that can inform contemporary politics.” Instead, he says, the series will have succeeded when people begin reading Arabic literature the way they read Russian or French poetry and prose in translation—”as real literature with its own merits.” Kennedy shares the sentiment: “I envision the series being a physical thing, where you can walk into a bookstore and see those rows of books—and people can see that there’s this huge tradition.”