Frederick Cook was celebrated as polar explorer extraordinaire then tarnished as a fraud. Now, long after his death, he’s redeemed

by Jennifer Bleyer

Early in the morning of September 21, 1909, a steamship emerged through a veil of fog in New York Harbor and churned toward the city. The Oscar II had set sail from Copenhagen 10 days earlier. As it approached lower Manhattan, half a dozen tugboats full of newspaper reporters flocked around it like so many pigeons.

“Standing at the North Pole, I felt I had conquered cold, evaded famine. I had proved myself to myself, with no thought at the time of any worldly applause.”

—Frederick Cook

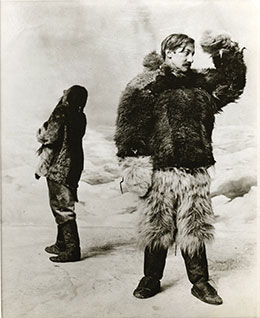

A roar went up when Dr. Frederick A. Cook stepped onto the ship’s deck. A sturdy man with broad cheeks, a rope-thick mustache, and a derby perched on his head, Cook was an Arctic explorer who had left the United States more than two years earlier with the formidable goal of trying to reach the North Pole—a feat no one had ever accomplished. During a long lapse in communication, he was thought to possibly be dead. Yet there he was, looking serene, triumphant, and very much alive. The newsmen barraged him with questions through their megaphones as Cook confirmed that he had indeed captured perhaps the holiest grail of global exploration. “I have come from the pole,” he declared.

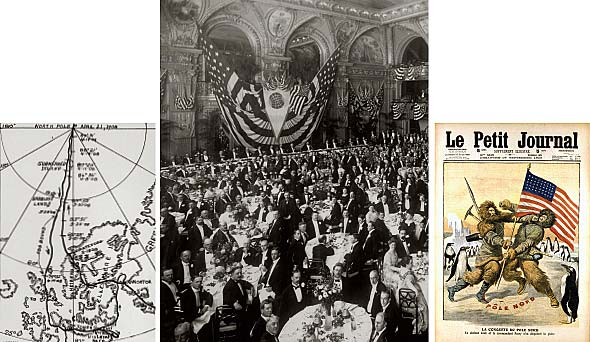

Cook, 44 years old and an 1890 graduate of NYU’s medical school, received a hero’s welcome that day. Wreathed in white roses, he was ferried by boat around Manhattan, saluted by steam whistles and foghorns, and applauded by massive crowds gathered along the waterfront. When he finally docked at the foot of South Fifth Street in Brooklyn, a crush of humanity enveloped him in a scene that one reporter described as having “all the elements of a riot except violence.” Trolleys stopped in their tracks and tens of thousands of people lined the roads as a band and a parade of 300 automobiles flying the Stars and Stripes escorted the adventurer to his stately red brick home at the intersection of Bushwick, Myrtle, and Willoughby Avenues. The house was adorned with a giant arch topped with a gold-painted globe and a larger-than-life portrait of Cook. Beneath the explorer’s picture hung a sign nodding to the controversy already brewing: WE BELIEVE IN YOU.

Shadowing his homecoming was the growing suspicion that his rival, Rear Admiral Robert E. Peary, was the true discoverer of the North Pole. Peary was a U.S. Navy civil engineer and accomplished explorer who had long fantasized this feat—a goal that seems to have been motivated by his single-minded, almost maniacal obsession with fame.

“My last trip brought my name before the world; my next will give me a standing in the world,” he wrote to his mother after an 1886 trip to Greenland. “I will be foremost in the highest circles in the capital, and make powerful friends with whom I can shape my future instead of letting it come as it will. Remember, mother, I must have fame.”

Backed by some of the wealthiest and most powerful interests of the day, Peary set off on a well-appointed expedition to the pole a year after Cook and claimed to reach it on April 6, 1909, again nearly a year after his opponent. That September, as both of them returned to civilization and publicized their claims in quick succession, Cook found himself interrogated furiously and shrouded in doubt. Their dispute dominated headlines across the world, and in spectacular fashion, Cook went from being toasted to being dismissed as a charlatan who had concocted a hoax of enormous proportion. Peary ultimately seized the torch as the North Pole’s discoverer.

Yet the question of who got there first, or whether either of them got there at all, persisted as one of the most inflamed and enduring controversies of the century. And in the past generation, as more information has emerged, a new crop of Cook defenders has risen up to reassert his accomplishment. Though both men have long been dead—Peary passed away in 1920; Cook in 1940—the controversy lives on.

Ted Heckathorn was a high school student in the early 1950s when he became fascinated by the early days of polar exploration. He devoured accounts of Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s journeys to Antarctica at the turn of the century, and he considered Peary among his greatest heroes. It was while in college at Stanford University that Heckathorn started to examine Cook’s story more closely.

The question of who got to the pole first, or whether Cook or Peary got there at all, is one of the most enduring controversies of the 20th century.

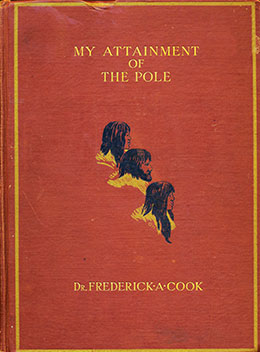

“Peary made statements to the effect that Cook was a liar who had faked his North Pole trip,” Heckathorn says. “I thought that would be fairly easy to substantiate, so I read articles by Dr. Cook, and his book, My Attainment of the Pole, and it was disturbing [because] it sounded very authentic. Looking at his exploration background, he was not what you would call a typical person trying to perpetrate something false.”

So began a lifetime passion for Heckathorn, who became a polar historian, writer, and mountaineer. Cook, he learned, was born in 1865 to German immigrants in New York’s rural Sullivan County in the Catskill Mountains. His family moved to Brooklyn, then an independent city, seeking greater opportunity, and he operated a milk delivery business with his brother while studying medicine at NYU. Just as he was completing his medical exams, his life took a tragic turn when his wife and child died following complications during labor, and he buried his nose in books about exploration to escape his despair. The next year, he heard that Admiral Peary was looking for a physician for an expedition to reach the northernmost point of Greenland; Cook volunteered immediately.

Their relationship was entirely collegial then: Cook admired Peary as a courageous and talented explorer, and Peary wrote of Cook’s “unruffled patience and coolness in an emergency” after Peary shattered his leg in an accident on the ship and Cook successfully set his broken bones. His appetite for adventure whetted, Cook went on more journeys to Greenland, both with and without Peary, as well as to Antarctica with the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897, and to Mount McKinley in Alaska, of which he claimed to be the first ever to attain the summit in 1906. (This last achievement also came to be questioned by Peary supporters.)

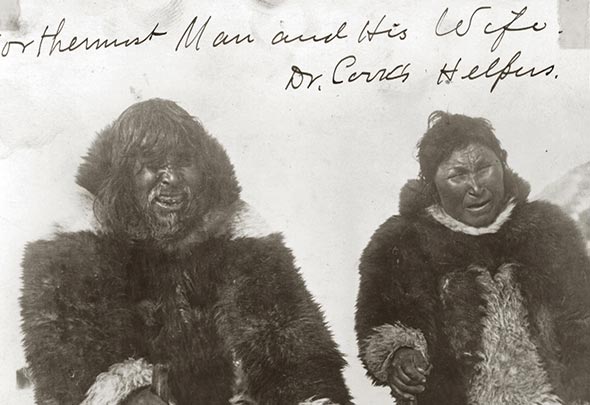

Increasingly striking out at the helm of his own expeditions, Cook devised a plan to reach the North Pole and set out on a schooner from the East Coast in the summer of 1907. He established a base camp at Annoatok, a tiny Inuit village in northern Greenland, where he passed much of the winter before setting off for the pole in February 1908 with his German deputy, 10 Inuit, 11 sledges piled with food and supplies, and 103 dogs. After advancing over the frigid expanse of the Arctic Archipelago, Cook said, he began his final 460-mile dash to the pole across the frozen Arctic Ocean with just two hardy Inuit assistants in tow.

Unlike the South Pole, which is fixed on a landmass, the North Pole is located in Arctic waters covered with constantly shifting ice, making it challenging to identify the exact point of the pole, a fact that Cook readily admitted. But on April 21, 1908, he said that he arrived at a spot on the endless snow-dusted ice pack where, according to sextant calculations and observations of the sun, the latitude was most likely 90 degrees North, and the longitude most likely zero.

“Standing on this spot, I felt that I, a human being, with all of humanity’s frailties, had conquered cold, evaded famine, endured an inhuman battling with a rigorous, infuriated Nature in a soul-racking, body-sapping journey such as no man perhaps had ever made,” Cook later wrote. “I had proved myself to myself, with no thought at the time of any worldly applause. Only the ghosts about me, which my dazzled imagination evoked, celebrated the glorious thing with me. Over and over again I repeated to myself that I had reached the North Pole.”

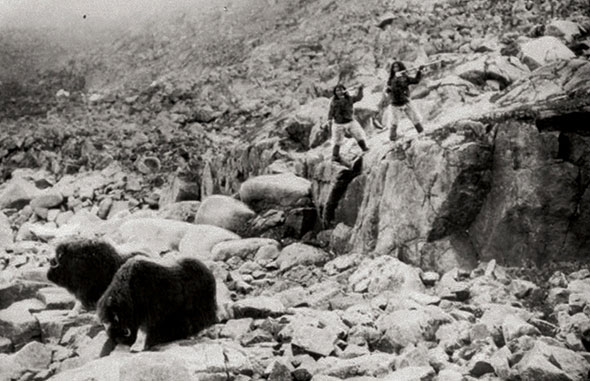

Now came a new challenge: When Cook and his two Inuit companions tried to return, they found the ice had drifted west. They spent the next treacherous year just getting back to the north of Greenland. They wintered over in a cave on Devon Island, all the while surviving on musk oxen they killed. By the time they returned to civilization, having reached the pole was almost an afterthought because they’d very nearly died of starvation and frostbite many times over.

Heckathorn became convinced that Cook was an explorer of extraordinary capability and perseverance, and he spent decades investigating Cook’s supposed accomplishments as well as the surreptitious campaign that Peary and his moneyed supporters launched against him. In 1989, Heckathorn found evidence that a Peary supporter had paid $5,000 (roughly $125,000 today) to Cook’s guide on the Mount McKinley ascent to publicly deny that they had even come close to the summit, a testimony that became key to challenging Cook’s overall credibility and North Pole claim. In 1994, Heckathorn participated in a Mount McKinley climb that retraced Cook’s route, offering geographic proof that he got much closer to the summit than most historians had concluded. And in 1998, Heckathorn went on two expeditions to the North Pole by Twin Otter airplane, mapping and confirming the land points that Cook described.

Cook’s redemption has found a champion in Russia as well. Dmitry Shparo is a renowned long-distance skier who, in 1979, was the first person to ever reach the North Pole on skis, and in 1988 skied across the Arctic Ocean from Russia to Canada by way of the North Pole. Shparo became intrigued by Cook’s story and spent years physically examining its veracity. In one effort, he led a team of mountain climbers in 2006 to retrace Cook’s disputed route to Mount McKinley’s summit, and came to the conclusion that Cook had indeed made the ascent as he’d asserted.

Shparo has also spent years poring over Cook’s writing and records, including the explorer’s papers archived at the Byrd Polar Research Center at the Ohio State University in Columbus.

“I have crossed the drifting ice for many thousands of kilometers,” Shparo says. “People say it was impossible to do what Cook said he did, but it was absolutely possible. I have the unshakeable conviction that Dr. Frederick Cook conquered the North Pole. He was not just an ordinary explorer. He was a genius.”

“I think Peary was an egomaniac and the last of the wave of explorers who were just out to plant a flag and say ‘I did it.’ ”

—Journalist Bruce Henderson

In December of 1909, a commission at the University of Copenhagen ruled that Cook had not provided enough evidence to assert that he had reached the North Pole, a ruling that the press pounced upon as definitive proof that he was a fraud. Yet herein lay one of the most sensational moments of Peary’s trickery, according to Cook’s supporters. Cook was said to have left three boxes of crucial navigational data he had collected on his polar trek with an American hunter named Harry Whitney in Greenland. Whitney later tried sending the navigational data home on Peary’s ship, but the admiral refused to let anything of his rival’s onboard. The boxes were stashed in the rocky expanse of Greenland and never seen again.

After this devastating blow, Cook retreated from the public eye, only to emerge two years later with My Attainment of the Pole, a lengthy and detailed account of his polar journey, as well as of Peary’s ruthless campaign against him.

“I claimed my victory honestly,” he wrote, “and as a man believing in himself and his personal rights, at a time when I was nervously unstrung and viciously attacked, I went away to rest, rather than deal in dirty defamation, alone.... I have now made my fight. I have done this because, otherwise, people would not understand the facts of the Polar controversy or why I, reluctant, remained silent so long. I have confidence in my people; more than that, I have implicit and indomitable confidence in Truth.”

Cook’s endeavor at self-defense largely landed on deaf ears—the tide of history had already turned toward Peary. Yet in a stunning development, Peary’s claim to the pole was discredited in 1988 after his long-closed papers were made public in the National Archives. A study of his navigational records and other notes suggested that not only was he never nearer than 100 miles to the North Pole, but that he knew and purposefully lied about his failing. Three-quarters of a century after the fact, the National Geographic Society, which had helped finance Peary’s expedition, acknowledged the findings, and The New York Times, which had led the media’s ferocious charge against Cook, printed a remarkable correction to its 1909 editorial commending the admiral’s discovery of the North Pole. Since then, other analyses of Peary’s papers have concluded that he may have reached the “near vicinity” of the pole.

Whether the truth behind Cook’s claim will ever be known with any certitude is unlikely, although it hasn’t stopped a new generation from inquiring. Journalist Bruce Henderson is the author of True North, a 2005 book about the polar controversy that portrays Cook as a man of far more decency, integrity, and sensitivity than Peary, and sympathizes with the defamation of character he suffered for the remainder of his life.

“I came to have a lot of empathy for Cook,” Henderson says. “I think Peary was an egomaniac and the last of the wave of explorers who were just out to plant a flag and say ‘I did it.’ I saw Cook as the first of the new wave of explorers who stopped along the way to meet the people in a cultural anthropological way. He learned how to speak with the Inuit. He became liked by them and cared for their sick.”

Yet even Henderson acknowledges that absent the navigational data or any other hard proof, Cook’s claim will probably always be a matter of conjecture—something that must be taken at his word. For Cook himself, that seems to have been enough, and the joy of his personal triumph never faded.

“That was my hour of victory,” he wrote of his excitement standing at the northernmost point of the world. “It was the climacteric hour of my life. The vision and the thrill, despite all that has passed since then, remain, and will remain with me as long as life lasts, as the vision and the thrill of an honest, actual accomplishment.”