music

Bohemian Symphony

DOWNTOWN MUSIC’S GLORY DAYS OWE MUCH TO MINGLING

by James Jung

In retro-fetishizing times such as these, it’s easy to believe that punk and New Wave single-handedly shaped New York’s 1970s and ’80s downtown music scene. But while bands such as the Ramones, Television, and Blondie grabbed headlines, the bohemian neighborhoods of Soho and the East Village were alive with a complex mix of sounds from superfueled punk, somber New Wave, minimalist classical, and rock-infused jazz. Often overlooked by popular culture, this cross-pollination gave birth to some of the most original musical collaborations, according to new research from the Downtown Collection, Fales Library’s eclectic archive on the art scene that flourished below 14th Street only a few decades ago.

ABOVE: THE PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE'S

UNIQUE DOWNTOWN SOUND FIT NO

CLEAR-CUT CATEGORY.

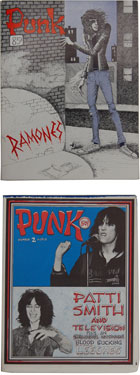

BOTTOM RIGHT: EARLY COVERS FROM

THE FANZINE PUNK, WHICH CHRONICLED

NEW YORK'S UNDERGROUND MUSIC SCENE

FROM 1976 TO 1979.

“In the ’70s, you had these clear breakdowns between genres— new music was performed at the Kitchen, punk at CBGB, and jazz in the artist-run lofts,” explains Peter Cherches (GSAS ’97), a prominent writer and performance artist from those heady days, who recently produced a comprehensive guide to the music of the period for the collection. “But by the ’80s, the distinctions between different genres got pretty blurred.” With this new understanding, Marvin Taylor, director of the collection, will pursue materials from a more diverse range of “downtown” musicians, such as Academy Award-nominated composer Philip Glass. “There became something that was downtown music,” Cherches continues, “but it wasn’t necessarily rock or classical or jazz.”

Nor did the new downtown music all sound the same. The musicians— from alternative rockers Sonic Youth to experimental composer John Zorn—blended the sounds of this era in different ways as they passed through the same milieu. Cherches says: “The unifying factor was more time, place, and culture as opposed to sound.” The movement culminated with the composer collective, Bang on a Can, formed in 1987 by three former Yale School of Music classmates. Noticing the fractured music communities in New York City, they kicked off the new society with a 12-hour marathon performance in Soho, featuring 28 young composers playing various musical strains.

While there is no definitive explanation for why this convergence of musical genres originally occurred, both Cherches and Taylor point to cheap rents in the then-counter culture meccas— Soho and the East Village—which attracted a slew of painters, musicians, writers, and actors who were sick of the commoditization of their work and intent on challenging artistic norms. According to Cherches, “The East Village was like a mutant small town of freaky artists within the city. This climate fostered collaborations born of social interactions among people working in different arts.”

Sadly, the period’s decline was sparked by the same factors that made it possible. Just as socioeconomics caused artists to gravitate downtown,by the end of the Reagan years, it began driving them out. “The stock market crash of the late ’80s killed off the East Village art market, and AIDS decimated the community,” Taylor explains. The closing of seminal venues, such as 8BC because of code violations, and the loss of some musicians to the commercial mainstream, contributed to the change.

Though there’s no telling whether a similar scene will resurface, Cherches doesn’t see it happening in New York’s now expensive downtown neighborhoods. And in our technologyinfused age,he isn’t sure whether it could happen within any of the city’s boroughs. “The Internet may have made the specifications of place less important, which is a shame,” he says, but adds, “You might say that it has created the possibility of a distributed bohemianism.”

Photo © PAULA COURT

“The East Village was like a mutant small town of freaky artists within the city. This climate fostered collaborations among people in different arts,” says writer and performance artist Peter Cherches.