museum

Brooklyn Canvas

A new destination for black artists

by Nicole Pezold / GSAS '04

Before his death in 2003, artist Tom Feelings longed to exhibit “Middle Passage: White Ships, Black Cargo,” his haunting charcoal and pen-and-ink drawings of the capture, abuse, and deportation of African slaves, in his native Brooklyn. The works had traveled to countless cities around the United States, but found no host in the borough—until the opening of the small, yet ambitious, Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (MoCADA), one of few dedicated venues for black artists in New York City, and the first in Brooklyn.

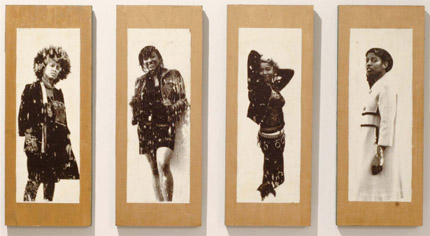

PHOTOGRAPHER TYRONE BROWNOSBORNE

IMAGINES THE MADONNA AS

ANY OF SEVERAL BLACK WOMEN ONE

MIGHT PASS ON THE STREET IN THIS

UNTITLED WOOD PANEL SERIES.

Even in a city with more than two million residents of African descent spread across five boroughs, contemporary works by black artists have for years been steered to the Studio Museum in Harlem or the nearby Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. That was unacceptable to Laurie A. Cumbo (STEINHARDT '99), founder and executive director of MoCADA. "You don't say, 'You have the Met,' and think that's enough [museums]," says the Brooklyn native who still lives on the same East Flatbush block where she grew up. "There's the Guggenheim, the Frick, the MoMA…."

Since its opening in 1999, MoCADA has provided a visual and cultural crossroads for Brooklyn's vast Diasporan communities—from Haitians to Nigerians to black Americans—with four exhibitions and 30 public programs annually featuring art-world stars such as Kenyan-born painter Wangechi Mutu, as well as new talent. Shows have ranged from painter Arturo Lindsay's rumination on his Afro-Panamanian roots to last spring's "The Post-Millennial Black Madonna," a group show on visions of the Virgin Mary by 24 artists, co-curated by Brooklyn painter and arts philanthropist Danny Simmons (WSUC '78)—brother of hip-hop magnate Russell Simmons—and event producer Brian Tate. MoCADA also sends artists into local schools and hosts an annual children's film festival to mold the next generation of black artists and museumgoers. "It's my goal to make sure that this is not a place where people feel intimidated, or that it has nothing to do with them," Cumbo says.

Rather, the 1,800-square-foot space often focuses viewers back on the events of the day, as in the case of Parisian Alexis Peskine's "The French Evolution: Race, Politics, & the French Riots," which debuted there in May 2007. Among the 15 mixed-media works inspired by France's 2005 riots and continuing racial tensions is "La Révolution de Marianne (Mariam)," a latex-on-canvas portrait depicting France's Lady Liberty, Marianne, as an African woman in a blood-red revolutionary bonnet. "It's important that this work be shown in Paris. The problem is that there are fewer opportunities there right now," Peskine says, citing both a less vibrant art scene and lack of access for nonwhite French artists.

For many years, a haven such as MoCADA was purely hypothetical to Cumbo,who had been drawn to visual arts since she scribbled in her first coloring book. As a graduate student, Cumbo studied visual arts administration at the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, where the idea for the museum started as a perpetual class project. "If they asked us to create a budget, or a Web site, or an exhibition, I'd do it for the museum," she remembers. "But it wasn't with the intention of starting an actual museum." However, with prodding from professors and a space donated by the Bridge Street AWME Church, MoCADA was born on the fourth floor of a Bedford-Stuyvesant brownstone. Since then, it has routinely drawn media attention, from the design magazine Metropolis to The New York Times, for both its aesthetics and mission. The Network Journal dubbed Cumbo a "keeper of the culture."

In 2006, in cooperation with the Brooklyn Academy of Music Local Development Corporation, the museum moved to the center of BAM's burgeoning cultural district in Ft. Greene—just one block from Atlantic Yards, the gargantuan, controversial building project that will include an arena for the New Jersey Nets and stacks of sky-rise condos. "It's better to be where the development and excitement is happening," Cumbo reasons, envisioning that MoCADA will grow with downtown Brooklyn and eventually expand to offer concurrent exhibitions. "The museum can be a marker that this community has a stake in this city."

From top: Photo © Christopher Questel/Courtesy MoCada

“You don’t say, ‘You have the Met,’ and think that's enough [museums], ” says Laurie A. Cumbo. “There's the Guggenheim, the Frick, the MoMA….”