In the free speech battles of today, It's not just students versus the establishment, but peer against peer

by Sarah Ivry

Last February, scores of news cameras and reporters planted themselves in front of NYU's Helen & Martin Kimmel Center for University Life, ready for a showdown between two camps of enraged students. At issue was a so-called game, Find the Illegal Immigrant, organized by the College Republicans and vehemently protested by the College Democrats, the ACLU, and various other parties who maintained the hyped event was, at its core, racist.

Though its rules were simple—one student would wear a name tag reading "illegal immigrant," while others, pretending to be border patrol agents, would hunt him down in Washington Square Park—its dimensions were decidedly complex. The savvy cat-and-mouse operation aimed at drawing broad public scrutiny both to illegal immigration and the bounds of free expression on campus.

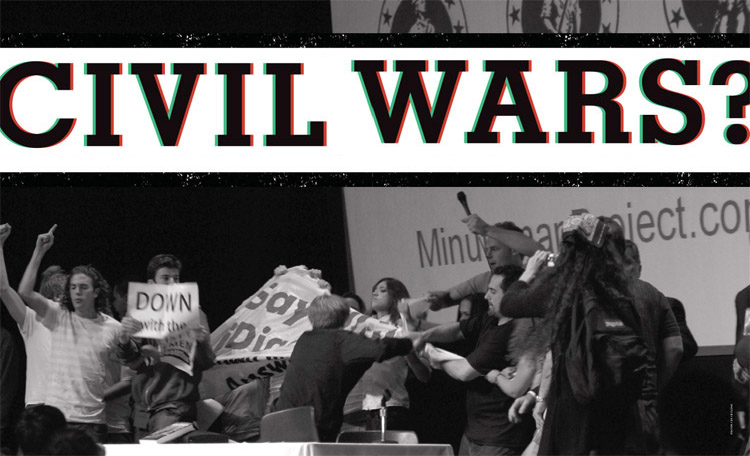

It was not an isolated event. Last November, at Michigan State's law school, protesters tried to prevent Colorado Congressman and Republican presidential hopeful Tom Tancredo from delivering a speech on immigration by pulling a fire alarm. A similar tactic was used to silence a speaker at Georgetown. Those incidents came on the heels of the now-famous video footage of Columbia students rushing the stage to shut down a talk by Jim Gilchrist, the provocative founder of the Minuteman Project, a volunteer group that patrols the U.S. border with Mexico in pursuit of illegal immigrants. The evening ended with some throwing jabs and uppercuts. Tensions have also been at a boil at the University of California, Irvine, where Jewish community members have protested events organized by the Muslim Student Union, with titles that link Israel to apartheid and a new Holocaust.

As angry debates on immigration, the war in Iraq, and other topics wrack the population at large, students likewise wrestle with these incendiary issues in a landscape of activism that less and less resembles the 1960s and '70s. Then, students enraged by the Vietnam War and the U.S. invasion of Cambodia occupied administration buildings across the country; antagonism reached a tragic apex at Kent State, when the Ohio National Guard killed several students, sparking campus strikes coast-to-coast. These days, there is no obvious generational rift, no muscular national student movement taking on government policy and the "establishment." Instead, campus activism more often mirrors the political sparring on cable television and the Internet, where peers provoke one another with sound bites and attempt to silence the opposition.

Campus activism more often mirrors the political sparring on cable television and the Internet, where peers provoke one another with sound bites and attempt to silence the opposition.

(TOP) LAST OCTOBER, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY STUDENTS STORMED THE STAGE TO INTERRUPT A CAMPUS EVENT FEATURING THE MINUTEMAN PROJECT, A VIGILANTE GROUP THAT PATROLS THE U.S. BORDER. "THE MINUTEMEN ARE NOT A LEGITIMATE PART OF THE DEBATE ON IMMIGRATION," ONE PROTESTER DECLARED TO THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER. (ABOVE) IMMIGRATION IS JUST ONE TOUCHSTONE ISSUE AT UNIVERSITIES TODAY AS WITNESSED BY PROTESTERS AT NYU LAST FEBRUARY, WHEN CAMPUS REPUBLICANS HOSTED A CONTROVERSIAL GAME CALLED FIND THE ILLEGAL IMMIGRANT. (ABOVE RIGHT) MINUTEMAN PROJECT FOUNDER JIM GILCHRIST BEFORE THE NOW INFAMOUS COLUMBIA MELEE.

Amidst these episodes, university administrators have become more mediators than foes, as they negotiate how to balance the principles of free speech, to which they pay credence, with students' safety and well-being. Administrators' varying positions—whether to allow a game such as Find the Illegal Immigrant to go forward, as NYU did, or to shut it down, as both Michigan State and Penn State opted to in 2006—indicate how precarious and cloudy the issue of free speech has become. While some observers laud a new era of outspokenness, others worry student voices are being increasingly stifled.

"Free speech and academic freedom are in very serious trouble," says lawyer Harvey A. Silverglate, co-author with Alan Charles Kors of the 1998 book The Shadow University: The Betrayal of Liberty on America's Campuses (The Free Press). In 1999, the pair co-founded the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) in response to what they see as a suffocating climate of suppression. The watchdog group monitors incidents of what it deems censorship and rates schools on their free-speech records. Most fare poorly by the group's standards. A 2006 FIRE report stated that of 334 schools surveyed, 229—including NYU, Columbia, Harvard, and Emory—received the worst possible rating, a red light. At the other end of the spectrum, only eight schools nationwide got a green light.

FIRE's ratings reflected, in part, events where expression may have been curbed. However, the institutions were graded largely on the number of written policies that, cobbled together, form a speech code of sorts governing student conduct and harassment, and which most universities forged out of a desire to promote tolerance and respect, rather than repression, on campus. To Samantha Harris, FIRE's director of legal and public advocacy, this is an insidious development that shields young people from real world realities. "There is this genuine belief that has grown on campuses that students have a right to not be offended," she says. "If your child graduated from high school and got a job or went to war or all the other things you can do at 18, they wouldn't have these kinds of protections; they'd be out in the world where they'd be getting their feelings hurt regularly."

New Faces, New Voices

The expanding presence of conduct and harassment policies is in part an outgrowth of a visible development on college campuses: diversity. In the past three decades, the share of minorities enrolled in college has doubled, from roughly 15 percent in the mid-1970s to 30 percent, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, a division of the Department of Education. More specifically, the proportion of Hispanic students has jumped from 3.5 to 10.5 percent; African-American students from 9.5 to 12.5 percent; and Asian and Pacific Island students from 0.8 to 6.4 percent. At the same time, the number of students from foreign countries has almost doubled, from 2 percent of undergraduates nationwide to nearly 3.5.

"You don't have to censor people when they all go to the same country club," explains Stephen Duncombe, a professor at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study who's written extensively on cultural resistance movements. "When you get people from different cultures, you have different ideas of what is appropriate to say. The tensions that go with free speech increase when you have a multicultural university, but that's all the more reason you need it."

What, though, has led some students to expect that they should not be offended or that they have the right to silence another's freedom of expression? The answer lies in the 1960s, says Robert Cohen, a professor of social studies education at the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development and co-editor of The Free Speech Movement: Reflections on Berkeley in the 1960s (University of California Press). In that era of radicalism, students were seen as adolescents in need of guidance, unable perhaps to defend against ideas they found objectionable. To help protect them, then, universities restricted free speech.

"There was less free speech than there is today," Cohen says. "Later the issue is once the students got empowered, what about people who didn't agree with the left, and that's where there was a lot of tension. If somebody came to campus who was pro-war, they'd get booed." Now, he adds, there is less discourse generally about political issues on campus, even though arguments over reproductive rights, immigration, and the war in Iraq dominate the news cycle. Instead, there is a proliferation of stunts, such as illegal immigrant hunts, masquerading as debate.

WHEN MINUTEMAN CIVIL DEFENSE CORPS FOUNDER CHRIS SIMCOX ROSE TO SPEAK AT AN NYU PANEL ON IMMIGRATION LAST SPRING, HE WAS SHOUTED DOWN AND HALF THE AUDIENCE TURNED THEIR BACKS. SIMCOX TOLD FOX NEWS IT WAS THE "MOST UNRULY" CAMPUS EVENT HE EVER EXPERIENCED.

Balancing Act

Sometimes universities find themselves on the front line of veritable conflicts, not stunts, which epitomize the complexities of safeguarding speech. In 2006, NYU was awkwardly placed at the center of the clash over cartoons that depicted, among other things, the prophet Muhammad as a terrorist. Cooked up by a conservative Danish newspaper, the images violated the Islamic law prohibiting the display of images of the prophet, igniting an international wildfire on the Web and riots across the Muslim world.

NYU's Objectivist Club, which anchors itself to the ideology of author Ayn Rand, had planned a forum on how various publications seemed to have silenced themselves by not including the images in their reportage of the controversy. When NYU's Muslim community—and Muslims from around the world—got wind of the club's intention to display the cartoons, they vehemently protested to school administrators. The Bengali Students Association even urged its members in an e-mail to "go to Ticket Central, get two tickets for this event, and rip them up." According to John Beckman, NYU's vice president for public affairs, because of the university's concern for what was brewing to be a severely contentious affair, they enacted one of the university's commonly employed policies, declaring that the Objectivists must restrict the event to students, faculty, and staff in order to show the images. The forum's organizers, facing the possibility that attendance would be sabotaged if limited to the university, reluctantly decided to open the event to the public—and not display the cartoons.

A roar of discontent rose up, both on and off campus. During the event, held under tight security with metal detectors, campus and city police officers, the Objectivists left empty easels on the stage as a reminder of the missing cartoons. In short order, the New York Post, The New York Sun, and USA Today condemned the university's decision, and FIRE's president, Greg Lukianoff, who spoke at the forum, wrote an open letter to members of NYU's board of trustees, president, and other administrators stating, "One cannot claim to value free speech but then take the side of angry censors."

Beckman says that FIRE's claims that NYU acquiesced in the face of pressure were false. "Universities start from the premise that their students, in fact the entire community, should be exposed to ideas other than the ones that they already believe," he says, noting that opening up the event to a university community of 60,000 was hardly restrictive. "FIRE chose a highly selective and misleading version of this story to give the media." Furthermore, Beckman believes that the heat the university took detracted from the ultimate goals of intellectual conversation. "Everyone would be well-served by approaching debates, particularly on charged issues, with an attitude that a thoughtful discourse is the best outcome rather than a shouting match." he adds.

Part of the issue at play in these episodes is that some students have never properly learned how to engage with ideas that are anathema to them. Cohen cites an e-mail he received from a student group organizing a protest intended to interrupt a speech by a representative of the Minuteman Civil Defense Corps as evidence. "I wrote back and said that's not a logical position," he explains. "You don't like their views, allow them here and protest their views, but I won't support disrupting their right to speak. Not only is that a problem for the university as a free forum of ideas, but also the issue won't be about their views on immigration, but about your reaction to free speech." The university, he says, should be more emphatic in teaching students how to challenge offensive ideas. Marc Wais, vice president for student affairs, says such instruction does already take place in broad terms during orientation for incoming students: "We don't have intensive two-day seminars, but it is articulated from the president on down."

Notwithstanding presidential requests for tolerance, folks such as FIRE founder Silverglate say free speech is in a constant state of peril. "Today the threat is much more pernicious because it comes disguised in the cloak of what we roughly can call civility, and more specifically the notion that civility conflicts with free speech and academic freedom," Silverglate says. "No college wants trouble on its watch. It's geared to avoid problems, and when you opt for safety over anything else, you can't possibly have a vibrant institution."

But if Silverglate seems a cynic, Duncombe is an optimist who thinks that there's something "precious" about using a word like censorship in relation to American universities, given the state of profound repression in China and elsewhere. If anything, he's encouraged by the proliferation of informal channels, such as Facebook and Wikipedia, that facilitate students' freedom of expression. "At no point in the entire course of history has it been easier to access facts and knowledge, because of the Internet," he says. "There are always those who will stand up and shout down other peoples' ideas…but by and large what I've seen is a lot more discussion than clamping down."

TOP PHOTO © KEN NGUYEN; LOWER PHOTOS BELOW FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: © DANIELLA ZALCMAN; © WILL DAVIS; ©ABC NEWS.COM/ASHLEY PHILLIPS; ©PHOTO BY DANIELLA ZALCMAN

"If your child got a job or went to war or all the other things you can do at 18, they wouldn't have these protections; they'd be out in the world getting their feelings hurt regularly."

—Samantha Harris, FIRE's director of legal and public advocacy