Xiao Yan, a goat butcher, rests during a break at the slaughter market in Changsa, the provincial capital of Hunan province and the site of much of Dundon’s photography on China’s disaffected youth.

Photographer Rian Dundon uncovers the youth left behind by China’s boom

by Christian DeBenedetti

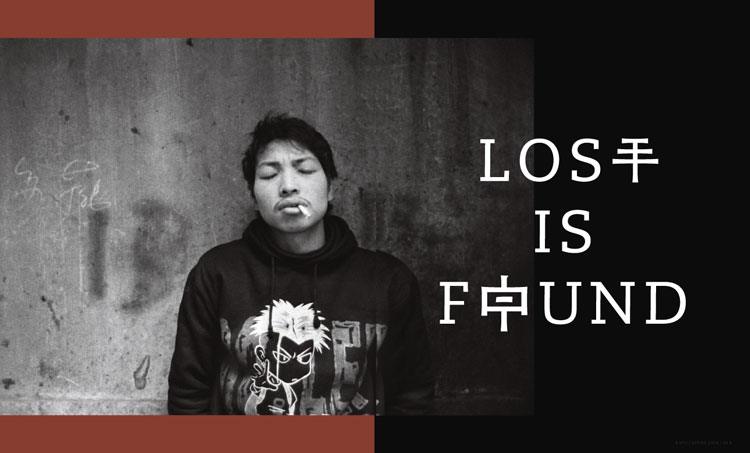

In 2005, when photographer Rian Dundon (TSOA ’03) first moved to the industrial mining town of Jishou, in China’s Hunan province, he didn’t have any friends there, let alone a plan. On a whim, he’d followed his girlfriend, who had landed a teaching fellowship. So he just wandered the streets armed with his Nikon FM2 SLR film camera and a New York sensibility, which came in handy because he spoke no Chinese. “I made most of my friends just hanging out, smoking cigarettes, and smiling at people,” he says, much like when he did “the struggling photographer-artist thing” while studying imaging and photography at the Tisch School of the Arts. Though the run-down city was at times daunting, there was something intriguing in its decay. To get by, Dundon, an Irish-American born in Portland, Oregon, taught English at Jishou University, where he picked up some conversational Chinese, and burned through 300 rolls of black-and-white film in eight months.

“I didn’t really know what I was doing at first,” admits Dundon, now 28 and living in Beijing. But he quickly realized that the place didn’t fit what he calls the glossy image of “Eastern model cities and the economic miracle of the new China.” In Jishou, and even more so in Changsha, the larger, ramshackle province capital where he moved a year later for a university job teaching English, he noted overcrowded, claustrophobic warrens of dilapidated high-rises. Next to wealth and prosperity, he found evidence of alienation and disaffection all around him. With little hope for academic success or financial wealth, scores of young people—the offspring of many government mandated one-child-only families—were caught in the slipstream of modern society, a fringe where recreational and hard drugs, alcohol, and a fatalistic resignation to the future hold sway even as a radical new individuality takes root. They’ve become China’s “lost generation,” remarked one photo editor at Time magazine, which recently featured some of Dundon’s pictures and writing.

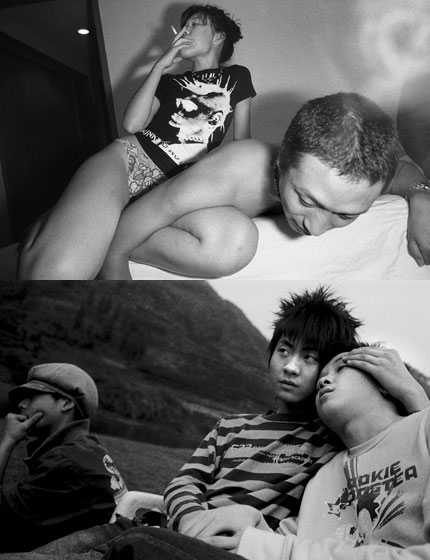

TOP: GAY TEENAGERS EMBRACE IN THE COUNTRYSIDE. BOTTOM: LOVERS FROM TIANJIN IN A BEIJING HOTEL ROOM.

The name “lost generation” is apt for the subjects in a number of Dundon’s works. Many Chinese born after 1979 are “caught between the older mind-set of their parents and modern society,” he says. Pressure to excel academically is constant and suffocating, and rather than fight the system, many simply drop out. Others flee rural communities to experience the sexual freedom and anonymity of China’s larger cities, where they band together in underground karaoke clubs to drink, perform, and experiment with sex and drugs. “They’re too ambivalent to be frustrated,” Dundon explains. “I think a lot of people feel powerless amid the pace of life and competition in China, like they’ve lost control of their own destinies.”

Ambivalence and melancholy hover like a smokestack’s haze in much of Dundon’s work, which earned him a Tierney Fellowship from NYU in 2007. One photo from his collection titled “Between Love and Duty: Chinese Youth Culture” depicts gay teenagers in the countryside commingled in a tentative but tender embrace; another, titled “Li Qiang Waits for His Bride on Their Wedding Day,” captures a man gripped in uncertainty, his fists curled, eyes narrowly searching the middle distance.

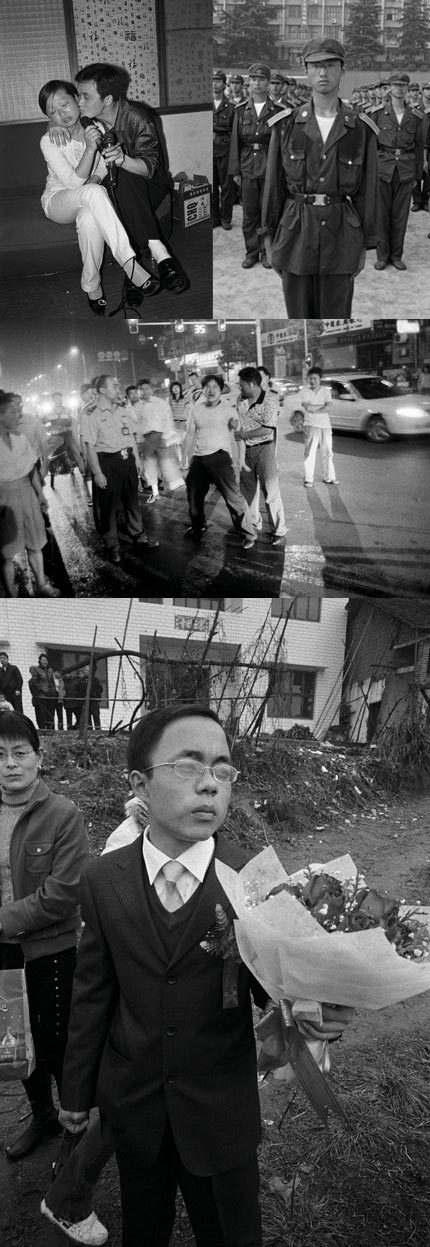

Dundon, who counts noted portrait photographers August Sander and Anders Petersen as key influences, explores other emotional dimensions, too. In one striking image, a crowd restrains a young Changsha man who, distraught over a girlfriend, had moments before attempted to kill himself by lying down in traffic. Another subject beams as he embraces his friend, a smiling transvestite. Still another writhes in pain, wounded from a fall off his skateboard.

Despite the sensitive nature of his work, Dundon has yet to earn the unwelcome attention of Chinese government censors. He works slowly and unobtrusively to gain the trust of his subjects, many of whom have become his friends. This familiarity has allowed him to photograph, for example, his university students in the midst of military training as well as intimate shots of ecstasy-addled clubgoers and couples in bed after dark. Some locals find it shocking. “Some say that I’m seeing stuff most Chinese people don’t see,” Dundon says. “And some don’t want to look at it. They don’t tell me that they don’t like it or that they don’t approve, but I can tell they don’t want to see that side of society. They think, Who’s this foreigner who wants to put China in a bad light?”

Dundon deflects such criticism by pointing out that he is merely documenting China’s convulsive cultural shifts and the emergence of new social classes, both rich and poor. His work, he argues, doesn’t sensationalize those pushing the fringes but let’s them tell their own stories. “Beyond the social context, this work is about human relationships,” he says. “Personally I think the pictures are uplifting—and a little bit joyous at times.”

TOP LEFT: A KARAOKE BAR IN JISHOU CITY. TOP RIGHT: UNIVERSITY FRESHMEN, SOME OF WHOM WERE THE PHOTOGRAPHER’S ENGLISH STUDENTS, DRILL DURING COMPULSORY MILITARY TRAINING. MIDDLE: A YOUNG MAN DISTRAUGHT OVER HIS GIRLFRIEND IS RESTRAINED MOMENTS AFTER ATTEMPTING SUICIDE. BOTTOM: LI QIANG, 22, WAITS OUTSIDE HIS BRIDE’S HOME ON THE DAY OF THEIR ARRANGED MARRIAGE IN XIANGTAN.

To see more of Dundon’s work, visit www.riandundon.com.

“Pressure to excel academically

is constant and suffocating, and

rather than fight the system, many

young Chinese simply drop out.

”