creative writing

Wunderkind in the Classroom

Novelist Jonathan Safran Foer discusses fiction—and how to teach it

by Catherine Fata / CAS ’09

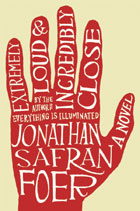

Jonathan Safran Foer went from receptionist to best-selling and critically acclaimed author with the 2002 publication of his debut novel, Everything Is Illuminated (Harper Perennial), when he was just 25 years old. Praised by the likes of Francine Prose and John Updike and winner of the Guardian First Book Award, the National Jewish Book Award, and the New York Public Library Young Lions Fiction Award, the novel announced the arrival of a brazen new talent to be reckoned with. The responses from critics were polarizing—everything from hailing him as a genius to calling his work gimmicky.With a second novel under his belt (Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, Mariner Books) and a work of nonfiction due out next year, Foer has joined the faculty at NYU as a professor in the Creative Writing Program. And it turns out that his pedagogical philosophy is as unorthodox as his literary style. David Grumblatt, an MFA candidate, recalls assignments as varied as oral storytelling, euology writing, and singing karaoke. “[Foer’s class] was much more focused on the process of writing, rather than the creation of a finished piece,” Grumblatt says. “We were encouraged to experiment, to be playful, and to question how we approached our own writing.”

During his first semester on campus last fall, NYU Alumni Magazine caught up with Foer, who is now 32 and, dressed in jeans and sporting a close-cropped haircut, can easily pass for one of his students.

As a teacher you must be reminded of how much effect one of your teachers—Joyce Carol Oates, whose class you took as an undergrad at Princeton—had on you.

I would not have become a writer if I hadn’t met her. She encouraged me when there was very little to encourage. Really. I didn’t know I wanted to be a writer. I didn’t think that I was particularly talented. I wasn’t producing work that was great. But she felt like she saw something that was worth, you know, fostering. And one lesson she helped me learn is that at that age, most people are very impressionable. A few kind words or a few unkind words can really send somebody into a different orbit. And she did that for me.

How can writing be taught?

What people are born with, more than any talent, is stories: where their families come from, how they talked around the dinner table, or didn’t talk, the conflict of their childhoods, things like that. In terms of my approach, it’s not to perfect pieces of writing but rather to encourage students to think about writing in ways they might not have before.… There’s plenty of time to perfect your craft, whereas when you’re a student, it’s a good time to have your basic notions of writing changed. So a lot of my assignments test the boundaries of fiction.

What’s your writing regimen?

That’s like saying, “What’s your regimen for getting out of a burning building?” I mean, stop, drop, and roll is generally a good idea. Be close to the floor is generally a good idea. Don’t breathe smoke. Don’t catch fire. Writing is a kind of emergency, it’s kind of a horrible thing to have to write. But I think ultimately each person finds his own way or her own way out of it. My regimen has changed a lot since I started. And I don’t really even have one now. I like trying to start in the morning, and I like trying to spend three or four hours a day doing it, but it doesn’t always happen like that.

Foer's mentor, Joyce Carol Oates, is an inspiration in his teaching.

Foer's mentor, Joyce Carol Oates, is an inspiration in his teaching.

And when it’s a struggle?

It’s really always a struggle. And I don’t say that flippantly. It really is always a struggle. And how do I work through it? Sometimes I just work through it. Sometimes I just put it down and go away and come back. Sometimes I have to put it down for a really long time, like weeks or months, and come back. And sometimes things have to fall apart in order to come back together in a way that’s good. But it’s hard. And not only does each writer face these problems differently, but each project presents different problems.

Does what you read influence what you write?

Everything influences what one writes—everything interesting does. I’m rereading a book, which is maybe my favorite of all books. It’s called Life? or Theater? by a woman named Charlotte Salomon. I only know about it because I happened to walk into a museum in Amsterdam where I saw it. It’s halfway between paintings and a book—just a total work of art. Every time I open it, it inspires me but also totally debilitates me because it’s so good.

Both of your novels are stories from different time periods intertwined into one. Is there a reason you chose to do them this way?

Sometimes there’s no reason for things in writing. That’s what’s nice about writing, nice about art. It’s not responsible to reason in the same way that everything else in life is.

Your books have been highly praised, but also harshly criticized. What is that like?

It was just, like, a matter of fact. It didn’t hurt my feelings or anything like that. I’d rather people like what I do than dislike what I do. But as long as people are having very strong reactions, then I’m happy. Because what I don’t want someone to say is, “It was a nice book.” I want someone to say that I really connected with it or I really hated it. And I would prefer the former, but I would take the latter over a lukewarm response.

photo © Adam Berry