NOW THAT AMERICA HAS ELECTED AN AFRICAN-AMERICAN TO THE HIGHEST OFFICE, MANY EXPERTS CONTEND THAT IT’S TIME TO DISCUSS RACE—FOR REAL

by Carlin Flora

It’s fairly effortless, and occasionally entertaining, to chat with your co-workers about last night’s Knicks-Lakers game or the latest moral failings of a state governor. But when newsworthy events with racial themes and overtones occur—such as the Jena 6 protests, the building of a fence on the Mexican border, or O.J. Simpson’s now legendary murder trial—we’re often too flustered for water-cooler talk or reluctant to share our true views for fear of upsetting or offending someone else.

Take the tragic murder of an aspiring actress on January 27, 2005. The next morning, New York City’s newspapers featured the tale of the beautiful 28-year-old woman who was mugged by seven teenagers on the Lower East Side and then shot and left to die in her fiancé’s arms. When NYU journalism professor Pamela Newkirk read the white victim’s biography in the papers, aside just a few sketchy details about the African-American perpetrators, she wanted to talk about how the teens got there, and how race had shaped their circumstances.

Just imagine the water-cooler problem therein: Talking about the kids’ disadvantaged past might look like an effort to excuse their violent actions. But Newkirk was running a class, and so she asked her students to retell the story. One, for example, profiled the school that some of the teens attended and found a high dropout rate, and a correlating high incarceration rate for those students. “This became less a story about a few bad apples,” Newkirk says, “and more a story about low-achieving schools as breeding grounds for crime.” The exercise got her students talking about race in new and more complex ways.

Such conversations, in theory, should have become easier since Barack Obama’s election to the presidency, which has infused Americans of all colors with great optimism. A CNN poll taken just before the new president was sworn in found that more than two-thirds of African-Americans believe Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision for race relations had been fulfilled. Some have even called this era “postracial.” Still others have balked at that characterization, given the race-based inequalities that persist in our society. But the need for frank, perhaps uncomfortable conversations on race is more urgent than ever given the expanding diversity of cultures and religions in the United States. By 2050, there will be no majority race—whites will make up just 46 percent of the population then, compared to 74 percent in 2006. By that same time, Hispanics will account for 30 percent, African-Americans 15 percent, and Asian-Americans 9 percent. Add into the mix a slew of class-based and religious differences and it becomes clear that in order for us to truly claim that America is “postracial,” some conversations will need to move beyond the reliable: “How ’bout them Knicks?”

Vital as they may be, we can’t expect breakthrough dialogues on race to occur spontaneously, especially where they’re needed most—in work and social-service settings. Erica Foldy, a professor in the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, is on a quest to understand how people can benefit from differences when they work and learn together. Research shows that diverse teams often perform worse than homogenous ones because those underrepresented within the group tend to either withdraw or assimilate, denying others their individual perspectives. Foldy believes it’s not diversity itself that brings down work teams, but rather the mismanagement of differences among members.

Even those specifically trained to confront race shy away from doing so, according to Foldy, who has tracked racially diverse teams of child-welfare workers who help families in crisis. She discovered that some of these workers consider themselves “color-blind” and rarely mention race. Others believe that race and ethnicity do matter but engage in what Foldy calls “race minimization”—they acknowledge race, but then downplay it. In observing 96 case meetings, Foldy says, only 14 team leaders referenced race and only five out of these addressed race in any depth. So although the professional norms of social work call for color-cognizance, the dominant behavior of these workers was avoidance. Perhaps not surprisingly, research shows that while practicing color blindness generally makes dominant groups feel more comfortable, it makes people of color feel less so. “We call race an undiscussable,” Foldy says. “It’s a taboo topic. I think the color blindness is a response to that.”

So how can social workers and others talk more constructively about race? In addition to encouraging color-cognizance, Foldy advocates that team leaders ask for feedback, review past work for errors, and display a general willingness to improve how they approach race-based issues on the job. Seems simple enough, especially since last November. However, Foldy cautions that Obama’s victory could actually increase workplace tensions. People may become less sensitive to the presence of discrimination, because Obama’s win supports the notion that the playing field has officially been leveled. “It may be harder for people to make a case for affirmative action now,” Foldy explains.

Despite the refreshing frankness of Obama’s now famous speech on race delivered in Philadelphia during the primaries, some observers also fear that the president’s conflict-averse style of governance may actually limit the national race conversation. In his new book, American Prophecy: Race and Redemption in American Political Culture (University of Minnesota Press), George Shulman connects the prophetic language of figures such as Henry David Thoreau, James Baldwin, and Toni Morrison to Democratic politics and, in particular, racial politics. Abolitionists and civil rights leaders, for example, often evoked biblical language to frame their struggles. Shulman, a professor at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study, notes that Obama’s striking lack of prophetic language signals his efforts to distance himself from a strong African-American tradition and appeal to a broader constituency. It is not coincidental, he says, that Obama mentioned Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln during his convention speech last summer, but referred to Martin Luther King Jr., only as “the preacher from Georgia.”

The same sometimes occurs in Shulman’s classroom. Even his most open-minded students can tend to underestimate the impact of race. “They do not see the invisible forms of inequality,” he says, noting that segregation is worse now than it was in 1965, while incarceration rates, infant mortality rates, and unemployment rates remain three to eight times higher for African-Americans.

Meaningful talk about race in the present requires an understanding of what came before. Too often history has been written by the majority and, intentionally or not, minorities’experiences have been presented more as sidebars to the true American tale. For her part, Newkirk is bringing intimate voices of the past to life in the new book she’s edited, Letters From Black America (FSG). In one letter to Abraham Lincoln, the writer laments how slow some were to follow the law after slaves were freed, suggesting that we shouldn’t underestimate the work ahead.

But this is just one thread of the larger American story. An enduring limitation of the race conversation in the United States is that it has traditionally been seen through a black-and-white lens, avoiding focus on other emergent ethnic groups. To move the conversation forward, we’ll have to understand the pasts and challenges facing immigrants from East Asia, South Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and all points in between.

A perfect example of this oversight, anthropologist Arlene Dávila says, was the frequent characterization of the Latino vote as a “sleeping giant” that woke up in 2008 to elect Obama. “It seems like during every major election, the Latino electorate is discovered, and then quickly forgotten again,” says Dávila, whose book Latino Spin: Public Image and the Whitewashing of Race (NYU Press) was published last year. While Latinos are our nation’s largest minority group, for instance, they are woefully underrepresented in our political system. And the fact that Latinos voted for Obama in large numbers doesn’t convince Dávila that their needs will now be addressed.

But as the histories of Latinos and other minorities are increasingly, if slowly, woven into the American fabric, some have experienced even greater obstacles. Since 9/11, and especially during the recent election season, there has been a growing tendency to conflate Muslim-Americans—or anyone with olive skin and a dark beard—with terrorists. Shulman notes that it was Colin Powell’s defense of Muslim-American soldiers last fall that helped draw attention to the anti-Muslim sentiment. “Powell’s point was that there would have been nothing wrong if Obama were in fact a Muslim—a point no one made during the campaign,” says Shulman, who adds that because blacks seem to be increasingly folded into the category of “American,” there is now this other, the Muslim, who marks the boundary of “non-American” for some.

The right setting goes a long way in facilitating race conversations. Newkirk was able to get her students to share their reactions to the murder of the young actress because she provided a safe environment, where everyone was asked to express their perspectives and respectfully accept those of their classmates. And they were relieved to be able to do so. “There seems to be a hunger for the kind of open and honest dialogue that even in the academy is often avoided out of fear of being viewed as racist,” she says.

One organization trying to make space for open, thoughtful dialogue is the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond, an antiracist initiative started in New Orleans that has created a workshop titled “Undoing Racism.” Last year, Dean Ellen Schall brought the workshop to the Wagner School where one participant was graduate student Ariana Hellerman, who grew up in New York City and considered herself pretty savvy to the different forms of racism in her midst. “There were a lot of ideas swirling around in my head,” she explains, “yet I never had a platform to discuss them because race isn’t usually discussed.”

Hellerman and her fellow attendees were asked to come up with slang words that people use to refer to poor communities. Examples were “ghetto,” “reservations,” and “el barrio.” They were then challenged to think of “institutional” words that are used to describe poor communities, such as “underserved,” “disadvantaged,” “at-risk,” and “low-income.” The question posed was how “ghetto” becomes “underserved,” and vice versa, and how seemingly innocent adjectives can promote old stereotypes. The talks still linger in Hellerman’s mind while she attends classes and works at her job in philanthropy, where she has noticed, for example, how the organization must employ two distinct languages to reach out to its local community and its more affluent donors.

One of the more discomfiting lessons from the workshop is that no matter which racial group we identify with, or what our socioeconomic status or political persuasion, everyone makes race-based judgments all the time. Perhaps this is truly the most honest starting point for the conversation to begin. As a song from the hit musical Avenue Q explains: “Everyone’s a little bit racist sometimes. / Doesn’t mean we go around committing hate crimes. / Look around and you will find, no one’s really color-blind.”

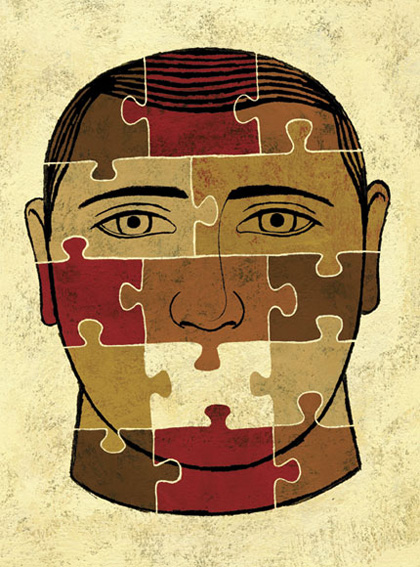

Illustration © James Steinberg

“Research shows that while practicing color blindness generally makes dominant groups feel more comfortable, it makes people of color feel less so.”

In order for us to truly claim that America is “postracial,” some conversations will need to move beyond the reliable: “How ’bout them knicks?”