NYU announces an ambitious bid to add as much as six million square feet across New York City—by its bicentennial in 2031

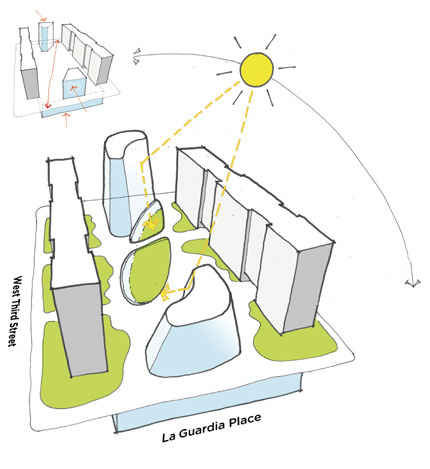

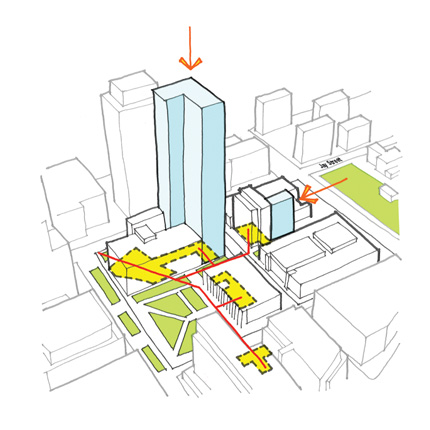

1. WasHington square village The strategy calls for retaining the Washington Square Village buildings while adding a new academic center, offering an opportunity to integrate the fragmented open spaces into a true urban landscape accessible to the public. NYU proposes two new academic buildings and maximizing below-grade space. The new landscape is envisioned as a pedestrian thoroughfare and area for interaction among students, faculty, and the public.

But imagine an NYU with expansive public lawns and gardens, modern classrooms where light shines in, landscaped pathways in place of fenced-off alleys, labs where students don’t stand touching shoulder-to-shoulder, and offices where faculty are able to fit books on shelves just like professors at other colleges do. Imagine an NYU that conducts research and scholarship not only at Washington Square but also on Manhattan’s East Side medical corridor, in Downtown Brooklyn, and even out on Governors Island.

Sure, it sounds like fantasy. But it may not be for long. The university, as a top-tier research institution, believes it can only move forward and maintain its place by offering some of the “necessities” that other schools enjoy. This thinking is the basis for the framework NYU has outlined in A University as Great as Its City: NYU’s Strategy for Future Growth. The roadmap, three years in the making and unveiled last spring, is a vision for expanding the university’s physical plant by 40 percent—some six million square feet—with a time horizon that stretches to NYU’s 200th anniversary in 2031. It envisions facilities from the East 20s and 30s health corridor to Downtown Brooklyn to Governors Island, creating remote academic centers that will benefit specific disciplines. Around the “core” in Washington Square, NYU will maximize use of its own property and will follow community devised principles for other areas of growth in the neighborhood.

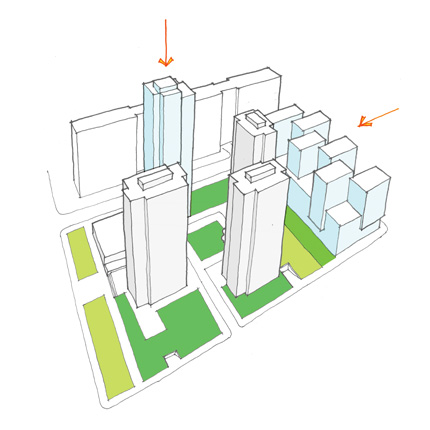

2. University village The strategy for the southern block is to add a residential fourth tower, as well as an expansive new playground at the supermarket site, to enhance and extend the existing “towers in the park” concept. In addition, a mixed-use building on the existing Coles Center site allows a great opportunity for a rebuilt gym and added retail, academic, and residential space.

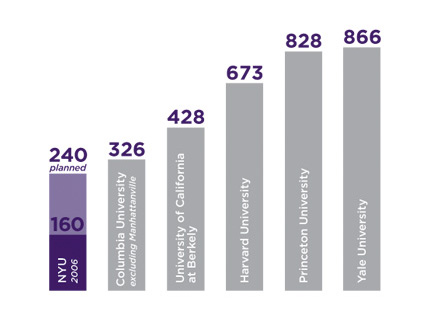

The goal is to help the academic centers across campus more easily conduct their work—not just make things roomier. NYU has spent billions hiring faculty and creating cutting-edge facilities over the past 20 years, but that doesn’t change the fact that everything is, in a word, constricted. Almost everyone, in every building, is starved for space. Currently, NYU has a mere 160 academic square feet available per student, compared to 326 at Columbia University, 673 at Harvard, and 866 at Yale. The 2031 plan would boost NYU to 240. As the plan says: “The university may look big and rich to its neighbors, but it is cramped and poor relative to its peer institutions.”

Indeed, NYU’s academic needs are ever expanding. Take, for example, the new Center for Genomics and Systems Biology, set to open on Waverly Place in January 2011. With 70,000 square feet of labs and classrooms, this expansion is essential to continuing NYU’s research, which aims to uncover the interactions between genes and the system that drives cell and organism functions. In the old days, scientists would analyze one gene in a test tube; now, studying one genome requires 30,000 test tubes. Robots the size of some New York City apartments will produce gene mutants alongside DNA sequencers and cameras that monitor the many experiments 24/7. All this activity—along with six research teams of 30-plus scientists and students—requires significant space. And just as genomics suddenly emerged as essential research in 2000 when the human genome was first sequenced, NYU needs to prepare for other breakthroughs in this new era of systems biology. “Every step we take opens another huge area of investigation,” says Gloria Coruzzi, chair of the department of biology, who notes that the National Institutes of Health recently expressed interest in using NYU’s new center as a design model for laboratories worldwide.

space per student Academic square feet per student

Just as you can’t conduct genomics research in a closet, you can’t properly rehearse for a huge, complicated musical in a tiny black box theater. Yet such has been the case at the Tisch School of the Arts, which has increased its student population from 500 to 2,000 since 1980 while remaining confined to the same 79,000 square feet at Broadway and Waverly Place. To solve that problem, Tisch aims to build a new Institute for the Performing Arts, which would include classrooms, soundproof studios, and a theater complete with fly space, wings, and an orchestra pit. As Dean Mary Schmidt Campbell notes, most NYU students “go through their entire college career without the experience of working in a truly professional theater. This would give them that chance.” And it’s not just about educating performers—the facility would connect the university to the downtown theater scene and provide new opportunity to students specializing in the electrical, carpentry, lighting, and costume design fields.

Overall, an undertaking like this has plenty of precedent in higher education. Similar transformations have been conceived by leading research universities, including Columbia, Fordham University, and St. John’s University within New York, as well as East Coast schools such as University of Pennsylvania, Yale, Harvard, and George Washington University. Additionally, NYU, which was recently ranked in the top 20 on Sierra magazine’s list of the “greenest universities,” is approaching every turn of the 2031 plan with attention to urban sustainability—from aggressive use of below-ground space to promoting pedestrian uses while growing along transit routes.

“New York City’s future economic growth depends on the strength and intellectual firepower of its great universities,” says Kathryn Wylde, president and CEO of the Partnership for New York City, a nonprofit organization of the city’s business leaders. “NYU’s expansion will ensure that the institution remains at the forefront of higher education, attracting great world talent, conducting cutting-edge research, and leading in global innovation. All these features of a vibrant university will translate into long-term economic benefits for New York.”

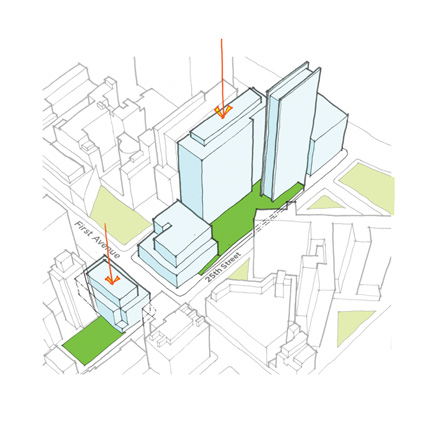

3. health corridor With an existing presence along First Avenue near NYU’s health facilities, NYU 2031 establishes the potential for incremental growth with the expansion and relocation of health-related disciplines.

Local and Not-So-Local Growth

NYU’s approach to space is different than that of many peer institutions, as it does not “bank” real estate—when the university develops or purchases space, it almost always puts it to use immediately. It also does not aim to purchase entire neighborhoods or blocks of land, as Columbia and Harvard did. Even in its core area, NYU facilities often sit beside non-NYU buildings. And it has demonstrated an unusual willingness to have space dispersed—consistent with the absence of campus walls and its “in and of the city” character.

With these principles in mind, the plan is for NYU to expand citywide and, simultaneously, in concentric rings. There is the “core” around Washington Square and the “neighborhood,” broadly defined from Canal to 18th streets and First to Eighth avenues. Finally, there are three “remote” campuses: Polytechnic Institute of NYU in Downtown Brooklyn; Manhattan’s First Avenue health corridor for medical, dental, nursing, and health sciences; and Governors Island, where NYU proposes to refurbish historical structures and build new facilities. In total, these remote spaces, once brought to fruition, will account for about half the space to be added away from the institution’s Greenwich Village heart.

The framework plan at the core, designed by the team of Grimshaw Architects, Toshiko Mori Architect, and Michael van Valkenburgh Associates, envisions about two million square feet to be inserted on and below the so-called “superblocks” south of Washington Square, between Mercer Street and LaGuardia Place, where the 30-story concrete towers known as Silver Towers/University Village and the Washington Square Village apartment blocks stand. The towers are legacies of the controversial 1950s slum clearance and renewal projects of the urban planner Robert Moses, built in the then-fashionable international “towers in the park” style.

The roadmap proposes building a fourth residential tower to house faculty beside the three Silver Towers, with a university hotel inside and underground parking. It would be taller than its companions (36 stories rather than 30) but would be inspired by I.M. Pei’s original modernist design in texture and feeling, and fitted into the other towers’ “pinwheel” configuration. The plans see a large new playground where the Morton Williams grocery store stands today (a new supermarket would open nearby) and improvements to the now-fragmented landscape.

Another move would be to raze the Jerome S. Coles Sports and Recreation Center. In its place would rise a large structure made of interlocking rectangles—hence its nickname, the “Zipper Building.” It would house classrooms on the lower floors, students above, and a new athletic facility below ground. An active, retail-oriented ground floor, including a supermarket, would enliven Bleecker, Mercer, and Houston streets, while new landscaping and pedestrian passages would invite the public in, linking NYU with the neighborhood, stitching the superblocks back into the original street grid.

On the superblock just north of this sits Washington Square Village, two long apartment blocks. They would remain, but the site would be transformed into a publicly accessible space with the current buildings continuing to face one another on two sides, and two new, rounded yin-and-yang-like, crescent-shaped, pyramidal glass academic buildings on the remaining two sides, fronting Mercer and LaGuardia. This would create a series of garden-like settings along with places to sit, wander, and play. NYU has also agreed to find on one of the superblocks adequate space to fit a new public elementary school, which it will donate to the city.

On Governors Island, an historic military base in New York Harbor sold to New York State in 2003, NYU envisions a waterfront campus surrounding a deck-like town square on a restored pier. A campus here could host up to 1,500 students at full capacity working in a single discipline, perhaps urban sustainability. An NYU study found that some historic structures could be adapted for housing both students and faculty.

Across the harbor in Brooklyn, change is already under way. NYU is set to complete its merger with Polytechnic between 2011 and 2013, and Poly’s current home in the MetroTech Center area presents an opportunity to think about not only expanded space for engineering and science but other NYU programs over time.

Back in Manhattan, a mile uptown from Washington Square, the expansion plan calls for a refurbished “health corridor” in the East 20s and 30s. In all, that site could accommodate more than one million new square feet on several potential development sites, for medicine, dentistry, nursing, and the health sciences. Work is already under way for a new facility on 26th Street for both nursing and dental research, as the nursing programs move from Washington Square to this health corridor.

4. downtown brooklyn NYU and Polytechnic University will merge between 2011 and 2013. The newly named Polytechnic Institute of NYU offers near-term and incremental opportunities for growth.

Making the Case

To succeed at something this grand, NYU realized it needs the support of its neighbors, elected officials, leaders in economic development and planning, and New Yorkers in general, and part of this effort lies in recounting how the university and the city are bound by an “inextricable link.” The strategic plan also notes the university’s sometimes-overlooked annual contributions from students, faculty, and the institution as a whole. Hours of volunteer service: 1.4 million. Taxes paid: About $125 million. Dollars spent locally: Some $800 million. Free care provided by the College of Dentistry: $30 million. Employees: 16, 475. Graduating students who remain in the city: 65 percent.

Just as noteworthy, however, is the strategic plan’s candid, mea culpa tone about past development errors, including a much-criticized, out-of-scale dorm on East 12th Street, which was assembled by a developer and then built under NYU’s direction and now houses more than 700 students.

Indeed, the 12th Street affair crystallized many issues underlying the university’s past growth. In the 1990s and early 2000s, NYU drew more and more students from outside the region. Beds were needed, and fast, as leases elsewhere expired. Decisions about solving the housing shortage happened ad hoc, under budget pressures, and with scattered internal communication. “It was a searing moment,” recalls Lynne Brown, senior vice president for university relations and public affairs, “at the end of which, we stepped back with a lot of leaders in the room and said, ‘How can we stop this from happening again? How can we do better?’ ”

Preventing history from repeating itself and being more forthright about the university’s plans is at the center of the 2031 effort. In his introduction to the framework, President John Sexton writes that the university is “part of a special, storied neighborhood to which we owe an obligation of care. NYU has not always recognized that obligation.” And because the local community is so sophisticated, and so suspicious, “NYU knew they had to put their cards on the table,” says historian Thomas Bender, a University Professor of the Humanities who sat on a faculty-planning advisory committee.

The question is: Will this newfound reflection sway the university’s biggest critics? It is a positive step, acknowledges Zella Jones, a Village resident for 35 years and member of an NYU-community task force, but there’s fear, too. “People are scared,” she says. “They’re scared that life is going to change. The university’s stance is, ‘Yes, we have sinned in the past, forgive us,’ and that’s a big improvement. We’ve come a long, long way. But we still have a ways longer to go.”

5. governors island On the island—a campus-like setting offering unparalleled flexibility and opportunity—NYU 2031 outlines the potential for a mixed-use center with academic programming, housing, student services, and retail. Such a center would require a critical mass of a university population and could be developed in phases, reusing many existing buildings.

Working with the Community

To devise the framework, NYU made good on its promise to seek dialogue. After rigorous academic planning, internal inventories, and assessments to determine its space needs, teams of planning consultants met with the community. This happened five times over 2007-08, at open houses with renderings and models on display, where activists and neighbors could fill in comment cards, talk with university leaders and the architects, and paste sticky notes on the exhibit boards. NYU incorporated the feedback into the new iterations of the plan, Brown says.

More formally, a Community Task Force on NYU Development also contributed. This group of officials and activists was convened by Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer and met with NYU more than 50 times from 2007 to 2010. The meetings were constructive but often tense. “More than ever before, New York’s economic success depends on finding a way for universities and their surrounding neighborhoods to remain fully invested in the city’s future,” Stringer says. “The Task Force has created the foundation for productive dialogue going forward. That’s a remarkable and important achievement, and bodes well for New York’s future.”

When NYU formally released the plan last April, the Architect’s Newspaper praised the designs, though noted they were rather large in scale. The WestView News community newspaper editorialized: “The proposal seems to be a sound one …[and] to have considerable merit.” The Villager most liked the plan’s commitment to the public school and added, “The work that NYU has done these past few years to better engage the community is to be commended.” Interviews with some community activists suggested that their demands were met for quality architecture and publicly usable green space. But some members of the Stringer Task Force had unequivocally opposed any expansion in the superblocks, so the notion of a fourth tower, and the Zipper Building, was poorly received by them.

Moses’ superblocks—love them or loathe them—are lightning rods for controversy, as they have been for decades. However, Brown notes that giving serious consideration to expansion beyond the Village and surrounding neighborhoods to areas such as Brooklyn, Governors Island, and the East Side of Manhattan was due to the community’s push. And the idea of including plans for a new public elementary school flowed from ongoing conversation with the community. There may be other “remote” sites that work for NYU in the future, with the right combination of academic rationale, ability to grow incrementally in those sites, workable finances, and adequate municipal services and amenities. This September, for example, NYU began conversations with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey about the future plans for lower Manhattan and what opportunities might exist downtown.

Joe Chan (WSUC ’93, WAG ’98), president of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, is “thrilled” to have NYU merge with Polytechnic and then greater expand its presence in the area, enhancing what is already a bustling collegiate community around the MetroTech area. “Practically speaking, it makes a lot of sense to target Downtown Brooklyn as one of NYU’s nodes for growth,” says Chan, noting that the area is one of the largest centers of mass transit in all of New York City. “We’d like to see as much NYU investment as possible.”

What’s Next

Planning may have been the easy part. Now comes the really tough stuff: securing the necessary government approvals for the superblock plans and ultimately the financing for such a big undertaking. NYU has already begun to assess the feasibility of a major fund-raising effort that will require the support of its 395,000-plus alumni, its trustees, friends, and the corporate and foundation communities. While NYU owns the property, its uses are heavily restricted by the terms of the old urban-renewal plans. The city’s historic-site regulators must rule on what, if anything, can be built beside I.M. Pei’s towers and the surrounding site, which were landmarked in 2008. And city planners must weigh in on what sorts of development can take place, at what scale, and for what purposes. The community boards and the borough president will also have a say. And the New York City Council must approve any final plan. It’s not unusual for a land-use review process of this extent to take two to three years.

It’s too early to say whether the design renderings in A University as Great as Its City will be built, if the square feet will be secured, if new structures will rise. What can be said so far is that those with differing opinions are talking to one another. “The university is definitely more responsive than they have been in the past,” says Community Board 2 Chair Jo Hamilton, who has requested a breakdown of the uses of all the square footage in the core, details on the new public school, and the exact timing of construction, among other things. “There are a lot of really good ideas, and a lot of questions and concerns. Will they get it right? We have to wait and see.”

Read A University as Great as Its City: NYU’s Strategy for Future Growth at www.nyu.edu/nyu2031/nyuinnyc. This fall, NYU will mount a storefront exhibit of its 2031 plan at 528 LaGuardia Place (between Bleecker and West Third streets), which is open to the public. All are invited to stop by and view the models and drawings.