nonfiction

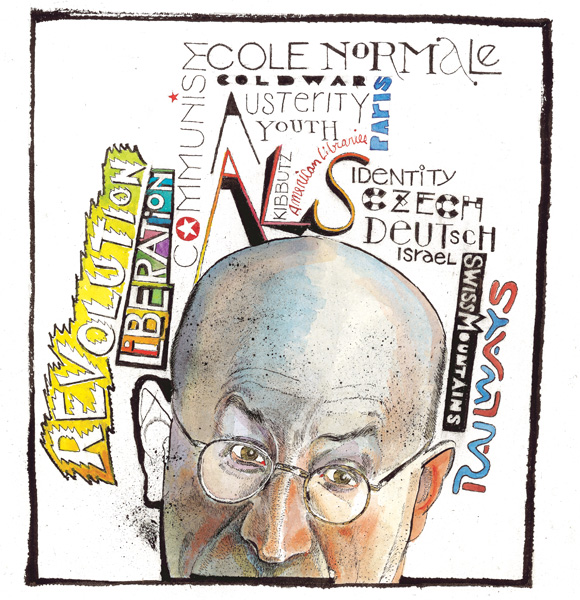

Tony Judt’s Last Lesson

Before his death, the historian offered up a future for social democracy

by Nicole Pezold / GSAS ’04

Chances are you’ve heard of Tony Judt. Perhaps it was his encyclopedic masterpiece Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 (Penguin) that first put him on your map or his public sparring over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Whatever the introduction, he was one of a handful of academics who has earned an unusual degree of celebrity. Remarkably, the intellectual agility that made him famous remained undiminished despite his recent affliction with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, a degenerative neuromuscular disorder also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Though paralyzed from the neck down the last year-and-a-half of his life, the University Professor who spent more than two decades at NYU, held forth on “What Is Living and What Is Dead in Social Democracy” at last fall’s Remarque Lecture. He memorized the entire two-hour address and delivered it with characteristic flair, gasping from a breathing tube he jauntily referred to as “facial Tupperware.”

Even Judt could not have predicted the reaction, not just to the physical feat of his performance but to the central idea he put forth—that government can still be a force for collective good. Afterward, young people in particular approached him curiously. “They sense something deeply amiss in the way we live but don’t quite know how to describe it or what they should be doing about it,” explained Judt, founder of NYU’s Remarque Institute, which promotes the study of Europe, in an interview before his death in August. The interest was so great that his colleagues at The New York Review of Books, whose pages have hosted many of his reviews and more recently a string of mini-memoirs, decided to reprint it as an essay. This led to a whirlwind book, his 14th, titled Ill Fares the Land (Penguin), which he composed in his mind and then dictated to an assistant.

The book’s title comes from Oliver Goldsmith’s poem The Deserted Village—“Ill fares the land/To hast’ning ills a prey/ Where wealth accumulates/And men decay”—and Judt viewed today’s dogged pursuit and praise of immense personal wealth as an erosive force to all of the positive public goods of the 20th century, from public transportation to Social Security. With an historian’s eye, he detailed the advent and subsequent disintegration of these programs, and how we may still salvage them. “The whole point is not to give up in the face of disappointments of the past generation, but use them to show alternative paths,” he said.

“I’m not especially optimistic,” Judt admitted, nonetheless he hoped the book would spark “at least a small conversation, out of which bigger ones might grow.”

The following is an excerpt from Ill Fares the Land:

Liberation is an act of will. We cannot hope to reconstruct our dilapidated public conversations—no less than our crumbling physical infrastructure—unless we become sufficiently angry at our present condition. No democratic state should be able to make illegal war on the basis of a deliberate lie and get away with it. The silence surrounding the contemptibly inadequate response of the Bush administration to Hurricane Katrina bespeaks a depressing cynicism towards the responsibilities and capacities of the state: we expect Washington to under-perform. […]

Meanwhile, the precipitous fall from grace of President Obama, in large measure thanks to his bumbling stewardship of health care reform, has further contributed to the disaffection of a new generation. It would be easy to retreat in skeptical disgust at the incompetence (and worse) of those currently charged with governing us. But if we leave the challenge of radical political renewal to the existing political class—to the Blairs and Browns and Sarkozys, the Clintons and Bushes and (I fear) the Obamas—we shall only be further disappointed.

Dissent and dissidence are overwhelmingly the work of the young. It is not by chance that the men and women who initiated the French Revolution, like the reformers and planners of the New Deal and postwar Europe, were distinctly younger than those who had gone before. Rather than resign themselves, young people are more likely to look at a problem and demand that it be solved.

But they are also more likely than their elders to be tempted by apoliticism: the idea that since politics is so degraded in our time, we should give up on it. There have indeed been occasions where “giving up on politics” was the right political choice. In the last decades of the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe, “anti-politics,” the politics of “as if” and mobilizing “the power of the powerless” all had their place. That is because official politics in authoritarian regimes are a front for the legitimization of naked power: to bypass them is a radically disruptive political act in its own right. It forces the regime to confront its limits—or else expose its violent core.

However, we must not generalize from the special case of heroic dissenters in authoritarian regimes. Indeed, the example of “anti-politics” of the ’70s, together with the emphasis on human rights, has perhaps misled a generation of young activists into believing that, conventional avenues of change being hopelessly clogged, they should forsake political organization for single-issue, non-governmental groups unsullied by compromise. Consequently, the first thought that occurs to a young person seeking a way to “get involved” is to sign up with Amnesty International or Greenpeace, Human Rights Watch or Doctors Without Borders.

The moral impulse is unimpeachable. But republics and democracies exist only by virtue of engagement of their citizens in the management of public affairs. If active or concerned citizens forfeit politics, they thereby abandon their society to its most mediocre and venal public servants.

From Ill Fares the Land by Tony Judt. Reprinted by arrangement of Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc. Copyright © 2010 by Tony Judt.