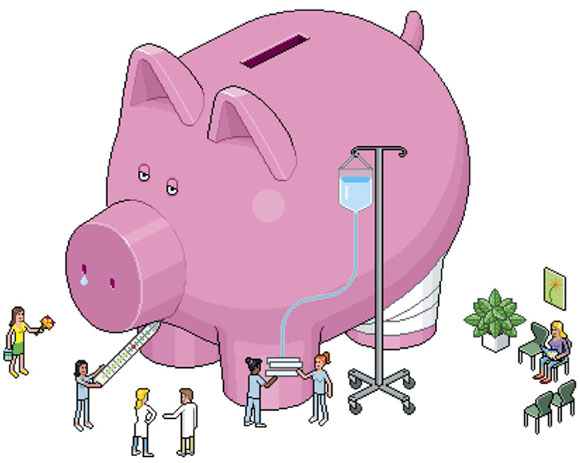

NYU policy experts look for unusual cures to the ailing health-care system

by Andrea Crawford

Testing assumptions is what scientists do, and John Billings seems to relish turning common knowledge on its head. When a visitor to his office in the Puck Building in New York suggests that electronic medical records—touted as a money-saving measure of the recently passed health-care reform package—will reduce costs, he corrects her. “They will—if the systems are linked,” clarifies Billings, associate professor of health policy and public service at NYU’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. And many systems, for reasons varying from patient privacy concerns to competing technologies, are not and will not be. Thus the health-care system will continue to fail at hand-off points: A primary-care doctor, for example, will not know that a patient has entered a hospital or seen a specialist, and hospital staff will discharge a patient back into the community and no one will know to follow-up.

When this visitor then proposes that preventative care is surely one remedy for our ailing, overspent system, Billings again clarifies: “Unfortunately, prevention doesn’t save much money.” Catching some cancers in their earliest stages may save on one patient’s treatment—and, most important, save a person’s life—but, Billings warns, “We’re going to spend a gazillion dollars finding that early cancer because we’ll be looking for it on so many people.”

Billings has identified one place, however, where better preventative care could save a boatload. The majority of Medicaid spending—some 80 percent—treats only 20 percent of patients, and Billings started investigating that high-cost minority a few years ago. Working first with data from the United Kingdom’s health-care system and then from Medicaid, Billings developed an algorithm that scans the details available in claims—such as age of patient, date of service, diagnosis, emergency room visits, specialty visits, pharmacy costs, days spent in hospital, and some diagnostic characteristics—in order to predict which patients are at risk of being hospitalized within the next year. And because a single hospital admission in the United States averages $8,000-$10,000 per visit, he showed that investment in the improved health and welfare of these few patients could create substantial savings. “This is one of the few cases,” Billings says, “where we think improving preventative care for a patient will actually save money.”

Government health departments on both sides of the Atlantic took note. So did his colleague Maria Raven, an emergency physician at Bellevue Hospital Center and faculty member at the NYU School of Medicine, who had an idea about what kind of intervention might help these patients. The physician, who had begun collaborating with Billings during a fellowship in medicine and public-health research, decided to use his model to study Medicaid claims at Bellevue; this would both validate the findings and establish whether the algorithm worked on a smaller data set. It did, and Raven identified Bellevue patients who fit the bill, but she knew that there was a limit to what information could be gleaned from claims. To devise a program to keep these patients out of the hospital, Raven needed to know more about them first. As Billings explains it: “I can learn a lot of their diagnostic history. I know how old they are, what providers they’re using, but I know nothing about their life circumstances. Her bright idea was, ‘Let’s go talk to them.’ ”

What Raven learned surprised her. While her team’s interviews with 50 patients and their providers confirmed much of what the data set had shown—frequent occurrences of substance abuse, depression, mental illness, and chronic disease—they also revealed significant rates of homelessness and precarious housing. “We found that the patients were in general very socially isolated,” Raven says. “Most have never been married and didn’t have many family or friends.”

It was suddenly clear that treating this population’s health problems required stitching them back into society’s fabric. Raven designed a medical intervention based upon social support. Though the pilot program required an extensive upfront investment in time, communication, and public resources—particularly housing—it appeared to reap real dividends for the patients and, by extension, taxpayers. When New York State, inspired by Billings’ research, created a $20 million Chronic Illness Demonstration Project to support high-cost Medicaid patients, Raven’s program was one of six that received funding. The three-year project, called Hospital to Home, operates at three New York City public hospitals: Bellevue in Manhattan, Woodhull Medical Center in Brooklyn, and Elmhurst Hospital Center in Queens.

Here’s how Hospital to Home works: The state department of health gives Raven a list of eligible patients, and case managers reach out to all of them, which is unusual since many social programs require sobriety. Raven explains: “We didn’t require our patients to be sober because that would be a barrier to care.” However, just finding those on the list can be difficult. So this summer, the program signed an agreement with the city’s Department of Homeless Services, which now cross-checks names from the state with shelter databases. Once located, only a few patients declined to join. At the beginning of the summer, the program had enrolled 230 patients, almost halfway to its goal.

Here’s how Hospital to Home works: The state department of health gives Raven a list of eligible patients, and case managers reach out to all of them, which is unusual since many social programs require sobriety. Raven explains: “We didn’t require our patients to be sober because that would be a barrier to care.” However, just finding those on the list can be difficult. So this summer, the program signed an agreement with the city’s Department of Homeless Services, which now cross-checks names from the state with shelter databases. Once located, only a few patients declined to join. At the beginning of the summer, the program had enrolled 230 patients, almost halfway to its goal.

Then begins what Raven calls an “intensive care-management system,” where a case manager is assigned to each patient. The manager’s job “is to make sure that everyone involved in the patient’s care is on the same page, and then to triage if issues come up.” The managers may attend doctor appointments and coordinate care across facilities. They escort patients to social-service appointments and ensure their Medicaid or other entitlement enrollments stay up-to-date. The program even provides patients with cell phones, so they can reach a manager at any time, if they are confused about a physician’s instructions, say, or have trouble getting a prescription filled. It also offers support groups to meet others. Each week, social workers, managers, and participating physicians do “management rounds,” meeting to discuss cases and monitor patient progress.

Meanwhile, Billings and Raven are looking again at Medicaid claims dates, this time to identify what health-care professionals call “super users” or “frequent fliers” of emergency departments. Reliance on emergency rooms is something often hyped as a high-cost abuse of the system, but Billings points out—again debunking common assumptions—that these visits are not expensive, since one typically costs about $200 or less. But “it’s the symptom that there’s something going wrong with this patient,” he says. The researchers hope to determine whether a certain pattern of use results in hospitalization, again identifying at-risk patients for targeted intervention. Billings says, “Everyone knows there are people who use the emergency room a lot, but what their characteristics are and what’s going on with them, people haven’t probed very deeply.”

It will be several years before Billings and Raven know whether Hospital to Home truly delivers. Regardless of the outcome, the majority of Americans will still face ballooning health-care bills. That won’t change—and medical costs in general will not be controlled—until the remuneration system changes, Billings says. “There are no incentives to be efficient now; the incentives are to use as much care as you can because everyone is paid on units of service,” he says. So any lessons gleaned from Raven’s intervention model aren’t going to work on a general population “until we have accountable care organizations,” Billings says, “where a group of providers come together and take full responsibility for all the costs of care.” Such groups would have incentives to provide quality care in the most efficient manner, both so patients choose them over another group and so they don’t price themselves out of the market.

It will be several years before Billings and Raven know whether Hospital to Home truly delivers. Regardless of the outcome, the majority of Americans will still face ballooning health-care bills. That won’t change—and medical costs in general will not be controlled—until the remuneration system changes, Billings says. “There are no incentives to be efficient now; the incentives are to use as much care as you can because everyone is paid on units of service,” he says. So any lessons gleaned from Raven’s intervention model aren’t going to work on a general population “until we have accountable care organizations,” Billings says, “where a group of providers come together and take full responsibility for all the costs of care.” Such groups would have incentives to provide quality care in the most efficient manner, both so patients choose them over another group and so they don’t price themselves out of the market.

Another potential avenue of reform would be to empower patients to make more health-care decisions themselves. Patients, it appears, tend to be more conservative than their doctors, says Billings, who, along with colleagues from Dartmouth College and Massachusetts General Hospital, co-created the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision-Making two decades ago. Their goal was to educate patients so that decisions about their care can be based more on their attitudes about benefits and risks, rather than on the physician’s. In the recently passed health-reform bill, Medicare authorized several studies to pay doctors to contract with someone to provide such decision-making aid to patients. “The bottom line is that a lot of medicine doesn’t have a real strong science base. So there’s a lot of discretion,” Billings says. “Some doctors do one thing, some doctors do another thing. Well, one thing often costs more than another thing. So when the incentives are to do as much as possible, it’s really hard to crack down on anybody.”

Saving money, of course, has not been the motivating factor for Billings in his three decades of research, teaching, and advocacy. “My work,” he says, “has focused historically on the needs of vulnerable populations”—research on the uninsured, low-income patients, and racial disparities in care. But this latest turn doesn’t seem such a departure when one considers that we’re all going to be a vulnerable population if health-care costs are not brought under control.

Closet Revolution

As every business manager knows, great efficiencies can be found in even the smallest of places. A team of students at the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, all of them full-time nurses, came up with one such cost-cutting measure, which they investigated in their Capstone project as part of the Executive Master of Public Administration: Concentration for Nurse Leaders program. They based their idea, according to Joelle Coq,

a student in the class and nurse manager at New York-Presbyterian Columbia University Medical Center, on a study done by the Robert Wood Johnson foundation that “looked at the amount of time nurses spend hunting and gathering equipment to get their job done.”

She and her five colleagues observed nursing staff at NY-Presbyterian, clocked the amount of time they spent with each patient, and photographed rooms after patients were discharged. What they found is that because nurses must bring supplies for each patient from a central storeroom, they tend to overload. And once supplies are brought to a patient’s room, they have to be used or thrown away. When they forget something, nurses must return to the central room, to and from which they are often interrupted. “If they have to stop in the middle of the task to get something else,” Coq explains, “that creates, first of all, a loss of time, but it also creates potential for error.”

Their solution? To turn each patient closet, which they noticed were rarely used, into nursing supply closets. They worked with architects, cabinetmakers, and the hospital’s materials-management department to create a model. Now, they’re testing its feasibility with a pilot project.

Open Wide

Physician Donna Shelley believes that the way to improved health care is through our mouths. One way to create greater access to care, reach vulnerable populations, catch problems earlier, and make health care in general more efficient, she notes, can be found in the groundbreaking collaborations now under way between dental and nursing professionals. “It’s becoming increasingly evident that there are many oral health problems that are a window into systemic problems,” says Shelley, who is director of interdisciplinary research and practice at the NYU College of Dentistry and College of Nursing.

Many major diseases have oral manifestations: One of the earliest ways to diagnose HIV/AIDS was through an infection in the mouth, and diabetes, for example, is associated with severe periodontal disease. Dentists are, of course, trained to treat periodontal disease, “but if we can encourage them…to think about what that periodontal disease might mean in terms of the patient’s systemic health,” Shelley says, “we might get more people who don’t know they have diabetes diagnosed and in treatment.”

One goal at NYU, which transferred its nursing program from the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development to the new College of Nursing within the College of Dentistry in 2005, is to make dentists, through curriculum and postgraduate education, more comfortable making referrals to their medical colleagues. And studies are under way to test the feasibility of doing HIV screening and implementing tobacco-use treatment in dental offices, for example, as well as offering dental care alongside nursing in senior centers and home health care.

At the same time, the schools have put both nursing and dental personnel together in their 14 clinics, where nurses have caught previously undiagnosed severe hypertension and diabetes in patients. “You know, they’re anecdotes,” Shelley says, “but you add them up and they start to be an improved model for treating patients.”

The majority of Medicaid spending—some 80 percent—treats only 20 percent of patients. “This is one of the few cases,” John Billings says, “where we think improving preventative care for a patient will actually save money.”

“There are no incentives to be efficient now. The incentives are to use as much care as you can because everyone is paid on units of service,” Billings says.