campus history

Remember The Triangle

A century later, New York refuses

to forget the fire that changed history

by Nicole Pezold / GSAS ’04

It was just about quitting time on Saturday, March 25, 1911, when the first tongues of flame licked across the eighth floor of what is now NYU’s Brown Building, but was then home of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. The fire jumped to the ninth then to the 10th, and top, floor. Along the way, scores of finished blouses, freshly cut patterns, and ubiquitous scrap boxes, fueled by rows of well-oiled sewing machines, lit up like greased tinder. Next door, in today’s Silver Building, NYU professor Frank Sommer and his law class heard shrieking and sirens. They scrambled to the roof, where students George DeWitt, Charles Kramer, Frederick Newman, and Elias Kanter lifted dozens of workers to safety. Within half an hour, the fire had mostly burned itself out; the modern building was, ironically, considered fireproof. Yet some 146 people were dead—most of them mere girls and recent Jewish and Italian immigrants. Trapped in unbearable heat, many had leapt from the windows, to the point that the first reporter on the scene wrote that the gutters ran “red with blood.”

Only the year before, these same women, on strike with the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, had demanded safer working conditions. Looking over the carnage, the reporter prophesied, “These dead bodies were the answer” to their unheeded call. Indeed, the tragedy shocked New York City and the nation into action, delivering many of the fire and building codes that protect us today, as well as routine drills, better inspections, and more humane labor laws. “A certain amount of air per worker, windows, clean bathrooms—all those things we take for granted were legislated as a result of the fire,” notes historian Richard Greenwald (GSAS ’95, ’98), dean of the Caspersen School of Graduate Studies at Drew University and author of The Triangle Fire, the Protocols of Peace, and Industrial Democracy in Progressive Era New York (Temple University Press). As the fire’s centennial approaches, many groups on and off campus are recalling this history with an array of activities—performance art, museum shows, courses, and no less than three TV documentaries—all culminating on the anniversary with the annual reading of the victims’ names at the Brown Building.

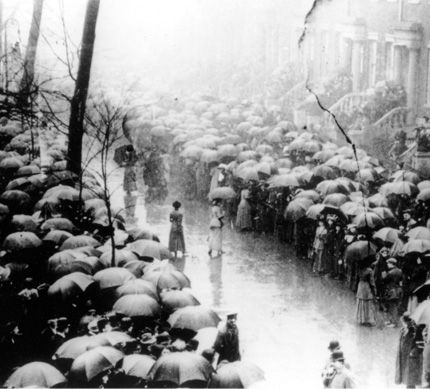

In the days after the fire, spontaneous memorials sprung up around the city, as newspapers opined about who was at fault and union activists called for more stringent codes and enforcement. The groundswell of public concern led to a mammoth relief effort for survivors and families of victims, and a solemn funeral parade for the seven women who remained unidentified. Despite rain, it drew some 400,000 participants and observers. It also put pressure on the political elite to respond and triggered a period of reform that would extend through the New Deal in the 1930s. In fact, Frances Perkins, FDR’s labor secretary, witnessed the fire from the street, while future U.S. Senator

Robert F. Wagner presided over state investigations in the aftermath. Both championed new regulations.

In the days after the fire, spontaneous memorials sprung up around the city, as newspapers opined about who was at fault and union activists called for more stringent codes and enforcement. The groundswell of public concern led to a mammoth relief effort for survivors and families of victims, and a solemn funeral parade for the seven women who remained unidentified. Despite rain, it drew some 400,000 participants and observers. It also put pressure on the political elite to respond and triggered a period of reform that would extend through the New Deal in the 1930s. In fact, Frances Perkins, FDR’s labor secretary, witnessed the fire from the street, while future U.S. Senator

Robert F. Wagner presided over state investigations in the aftermath. Both championed new regulations.

Reform is just one focus of a spring show at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery on how the tragedy has been commemorated over the past century. The exhibit is the labor of an ongoing interdisciplinary course for graduate students in the Archives and Public History and the Museum Studies programs, and will incorporate painting, sculpture, historical documents, and photos. Though students are still creating the exhibits, one highlight will be several sculptures by Evelyn Beatrice Longman, a protégée of American sculptor Daniel Chester French, who was quietly commissioned by the city’s elite to carve a memorial for the unidentified remains. The city purposely installed Longman’s marble relief of a garment worker at the Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, far from the grieving immigrant masses of downtown Manhattan.

As the event moved into the past, there was a span of decades when unions appeared to be almost the sole stewards of its memory. Now that’s shifting again, says Marci Reaven (GSAS ’09), director of the cultural conservation project Place Matters, who is co-teaching the NYU course with Lucy Oakley, education and program coordinator at Grey. “One could imagine that with industry moving out of the city and union membership down generally, no one would pay attention,” Reaven says. “But they are.”

This is because “there’s a sense of the pure wrongness of it,” says artist Ruth Sergel (TSOA ’08), who, since 2004, has organized a group of volunteers to haunt the neighborhoods where victims lived—primarily the East Village, Lower East Side, and Little Italy—and chalk their names, ages, and addresses onto the sidewalk before their former homes. Though the annual, if impermanent, memorial started with a low-key e-mail blast to family and friends, Sergel has drawn an increasing number of participants, and in 2008, sensing the coming centennial would need a central organizing body, she founded the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition. “You have the labor movement, Jewish-Americans, Italian-Americans, women, immigrants—they all feel passionately invested,” she says. Some see parallels with the plight of undocumented workers who toil today in meat factories and on farms and construction sites. For others, Triangle resonates with a more recent, though starkly different workplace trauma, 9/11.

Then there are those who feel a bit of déjà vu, as if American society had returned to the Gilded Age with the recent string of regulation-related catastrophes, from the financial crisis to the BP accident in the Gulf of Mexico. “The oil spill, it’s really Triangle all over again,” says Daphne Pinkerson, producer of HBO’s Triangle documentary, which will air next spring. While fire drills and sprinkler systems were known to significantly reduce injuries in 1911, for example, government was reluctant to trample on the liberties of the private sector. Then, like now, “The business of government was really to help business,” explains Michael Hirsch, a researcher and collaborator on the film. “But that changed after the fire.” Unlike the many other documentaries that have recounted the incident with authors and historians, the HBO film will look at it through the stories of the descendants of victims and survivors. To do this, Hirsch tracked down about 25 relatives, some of whom are featured in the documentary.

For Hirsch, the search for family members is part of a larger project to create an association of descendants so that they may have a voice in how the event is remembered going forward. There is a movement afoot, for example, to build a permanent memorial on or near the site of the fire, now noted simply by two retiring plaques on the building’s facade. The most lasting monument, however, may be all the lives saved since that fateful day. “American history is filled with these kinds of tragedies,” historian Greenwald muses. “In very few do you see something positive rising out of them.”

The modern building was considered fireproof. Yet some 146 people died—most of them mere girls.