A lost mailbag from the 18th century binds the past to our present

by Renée Alfuso / CAS ’06

“Dear sister, I cannot but apprehend your silence these 20 months past. It’s true that you can’t find an opportunity so often, but […] I am in great confusion about your health and welfare, not knowing whether you are dead or alive.”When he wrote this letter from France in 1757, William Cunningham was one of the many Irish expatriates cut off from his homeland by the Seven Years’ War. He couldn’t check his sister’s Facebook status or send her a quick text—he couldn’t even reach her by rotary telephone or telegraph. The only way to bridge the 600-mile gap separating his family was to find a ship captain willing to transport his urgent message and pray for its safe delivery.

But the letter never reached its destination. Instead, the Irish trading vessel was captured off the coast of France in the Bay of Biscay by an overzealous British privateer who ignored the ship’s passports, which should have allowed it to cross enemy lines during the war. Everything on board was seized as evidence for the court and brought to London, under the wrongful suspicion that the ship was trading with the enemy. The mailbag filled with birth announcements, news of deaths, and anxious pleas to relatives sat untouched for centuries.

That is until an equally overzealous history professor discovered the letters in 2011. Amidst the millions of documents in the British National Archives, Thomas Truxes was busy researching a book he was writing on the overseas trade of colonial America. He always relishes exploring its collection of uncataloged boxes, so he set aside some time and randomly requested a few to sift through for fun. “But when I found the Irish letters—everything stopped,” he recalls. “I really had to sit and just catch my breath because I knew instantly that I found a very rare thing.”

The bundle of 125 letters, most with their wax seals still unbroken, were written largely by members of the Irish community living in France’s Bordeaux region to family, friends, and business associates back in Dublin. As a time capsule from 1757, their discovery offers a uniquely candid glimpse into the lives of ordinary people who never imagined that anyone else would ever read them. “What makes the collection is that they’re not writing for effect,” Truxes explains. “It isn’t the social elite carefully studying their words and putting on airs. This all has an absolutely authentic, intimate voice.”

Historical letters usually come in highly structured collections because the families who keep them edit out anything that’s too personal or embarrassing. But because this mailbag was never delivered, its contents weren’t arranged or prettied up for posterity. Rather, the random sampling of voices echoes the sounds of 18th-century streets. “It’s very rare to find a collection that has this cross section of humanity,” says Truxes, clinical associate professor of Irish studies and history. “Archivists can find all the letters of Abigail Adams to her husband—but we don’t get the servant, we don’t get the guy who drives the carriage, or the man working in the field.”

Earlier this month the letters were put on display at Bobst Library for an exhibition celebrating the 20th anniversary of NYU’s Glucksman Ireland House, and Oxford University Press published The Bordeaux-Dublin Letters, 1757: Correspondence of an Irish Community Abroad, which Truxes co-edited with Trinity College Dublin professor emeritus Louis Cullen and NYU’s John Shovlin, an associate professor of early modern European history. The letters were reproduced without imposing a 21st-century syntax so that they reflect the period in which the definitive rules of spelling and punctuation were only just beginning. Truxes says that what’s striking is how familiar they sound despite the antique writing style and varying levels of literacy: We find students writing home to ask their parents for money and new clothes, as well as fathers chastising their children for being disobedient or lazy. “They reinforce a common humanity across time [because] the people we see in these letters are no different from today,” Truxes says. “Their conversations are very similar, so once you get beyond the handwriting, 250 years just melts away.”

The 1757 Bordeaux-Dublin Letters exhibit is currently running at Bobst Library through March, but here’s a sneak peek, along with some expert insight from Thomas Truxes:

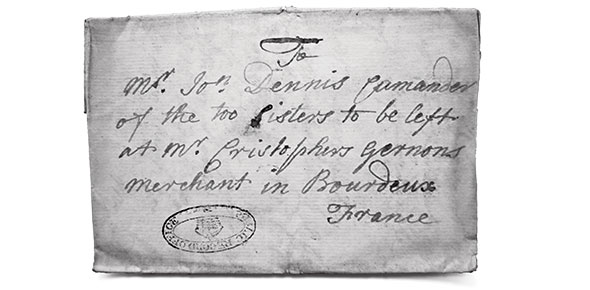

Excerpt from “Mary Dennis, Dublin, to Mr Jon Dennis, Comander of the too Sisters, to be left at Mr Christopher Gernons, Merchant in Bordeaux, France”

My dear life,

I take this opertunyty to let you know I am in good health & I hope this may find you in ye same it is ye greatest blessing I Desire if I cold hear you were safe & well I have bean very uneasey this past bad Wether but I trust in god for a happy Sight of you as there is an imbargo I think it Wold be proper to bring What you can to sell in ye shop as to reasons & paper fine & Corse & nuts & evry thing as befor ollivfs & peper if cheap for it is 2s per [ream] hear it is better have a Stock & you may Remit C munny for them at yr Return […]

My Dr I beg you will not omit Riting as it is ye onely Pleasure I Can have in yr abstance I beg you may take care of your self & I beg of the Allmyty God to Preserve you from all Eavill & grant me a hapy sight Wich is ye Fervent prayers of

YOUR LOVING AFFECTUNATE WIFE WHILLST

MARY DENNIS

P.S. My Dr I have had a bad Custom of yr sweet Company wich makes it worse to beare but I hope ye allmyty will grant me yt blesing onst more if I had but one line from you I shold think my self happy

Truxes: “We think of women of the era as being absolutely voiceless, but that’s not true. They just have a very muted voice because we don’t have a lot of them speaking. One of the very best letters was written by the ship captain’s wife. It’s a touching love letter in the most gorgeous English, but in the midst of it she is also reminding him that when he’s in Bordeaux, don’t forget to buy olives because [they] can get a good price for them, and also to bring back prunes. It’s just so real; it’s the wife saying, be sure you bring home the loaf of bread and the quart of milk.”

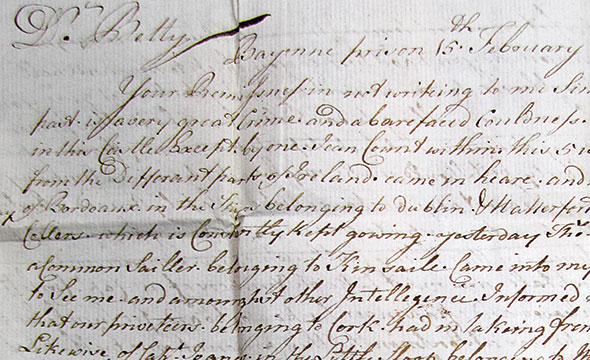

Excerpt from “Richard Exham, Bayonne Prison, to Mrs Richard Exham, Georges Street, Cork”

Dear Betty,

Your Remissness in not writeing to me Since the 22d Novr past is a very great Crime and a barefaced Couldness, and is unprecedentd in this Castle Except by one. […] Thus you see what a Just Reason I have to Condem you Whom I was never willing to bleame and in this my great Affliction being shut up from all Communication Except our fellow Sufferers whose Number are upwards of 500. I am now thank god on the mending hand from A Violent Sickness which brought me very Low and am at present very weake and wholly liveing by Grule. […] I should not be in this prison now had you duly advised me of Such steps taken in my favour to procure my Liberty but […] now all Opertunities is shut up and without any hopes for relife must heare Continue in this filthy Castle […] on this Occeason You thought a Creditt for 300 livers was of the greatest Searvice but in that Maddame Give me liberty to undeceive you. I could have gout 1000 livers in this pleace without your Assistance.

YOUR INDURED & AFLICTED HUSBAND

RICHD EXHAM

P.S. You have your easey bead by night and your warm house and Searvants at Command, Whils I am Confined within this dark Castle where is nothing by beare Walls and a Could flowr to Ly on Except boards under us for which we pay Extravigently. You night and day have Ease and pleasure Whilst I have nothing but Bitterness and Affliction.

Truxes: “This guy is an Irishman in prison in the notorious Bayonne Castle, and he writes this bitter letter to his wife that is so mean-spirited. He comes across as a colossal jerk because he’s angry with her, saying, ‘You get to sleep in your nice warm bed in Dublin and I get to suffer here.’

And in the same prison is a young man who’s writing a love letter to a woman in Ireland he’s courting, saying to her, ‘Every day I think about you and we will be together soon, I am so hopeful.’ So the first one is saying, ‘I’m never gonna get out of here and it’s your fault because you didn’t find a way to get me out, you’re letting me rot in this hellhole.’ And the other one is, ‘Don’t worry about me; I’ll be there soon,’ and they’re in the same place at exactly the same time—it’s so cool.”

Excerpt from “Mary Flynn, Bordeaux, to Mrs Catrin Norris, Liveing Feaceing the blackelying in [Facing the Black Lyon Inn], Temple bare, Dubllin”

My dear sister,

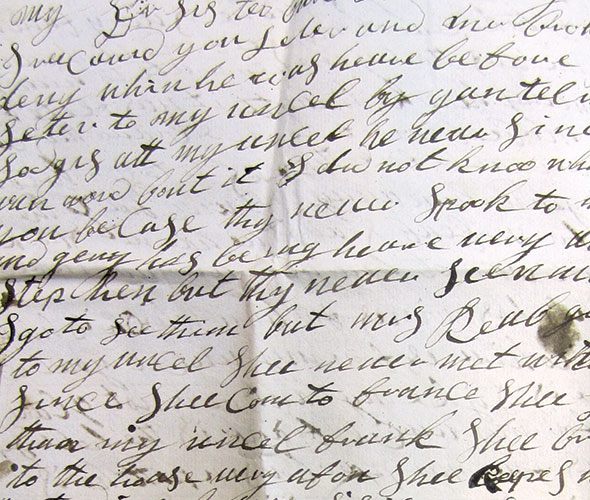

I receivrd you Leter and mr Broks by Captin deny whin he was heare before I sint your Leter to my uncel by gantelman who Lodgis att my uncel he nevr sint me anw wan word bout it I did not knoo what to say to you be Case thy never spook to me my ant and geny has being heare very afon and Stephen but thy never seen me nor did I go to see thim but mrs Beab gose very afon to my uncel shee never met with anny budy since shee com to france shee Likes more than my uncel frank shee brings him to the house very afon shee keepes him to sup An to dine […] the next nite there was muskc and hear he was danssing till midnit Mr Beab mead him sleep hear what he never don before thy kepth wontin them heare to dine with them hear this next munday […]

My Dr Sister I hafe meas in to pray for you for I am as hapy as anny gireal that ever leaft irland but that I am confind because I haf the ceare af the house for whin thy ear with thin I am bleaght to be within an whin Thy ear out I am bliaght to be within so I am confind and whin thy dyne brad I head thyr teable an whin thys with in I sit long with thim in […] mr beab gave me 12 lyons of preasint for my vooyeaug giufte he tould my uncle frank that night he suped heur wee had pankceaks that hed did not leave to hafe his super will don wans I had hand in it I say mr beab I bleave my uncel frank is glad I am come becouse mr beab is so fund of me fou he was very bad sick since I com heare and I toke great cear of him that mealke him to be so fund of me I concloud

YOUR EVER LOVING SISTER

MARY FLYNN

Truxes: “This one is just about impossible to read because she is barely literate and probably a teenager. It’s entirely phonetic, but it makes perfect sense if you just sound it out with an Irish accent. It’s a letter from a servant girl to her sister in Dublin, and she’s just gossiping about the house and the guys who come in and flirt with her, like little backstairs stories, but you can just picture this very young girl chitchatting away to her sister. So you get a sense of people coming and going, but she’s always stuck in the house. She’s literate in the sense that she can get her ideas across, but she’s not polished. It has the voice of the Irish countryside, but it’s all stream of consciousness.”

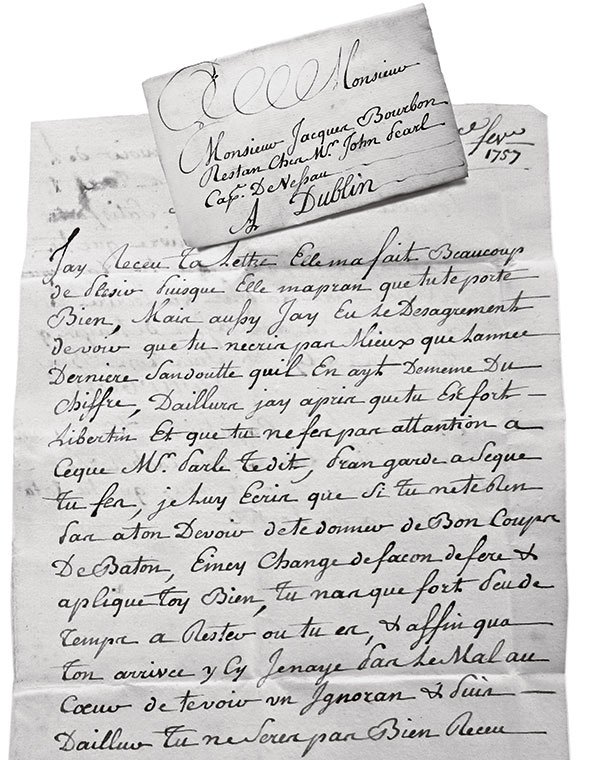

Excerpt from “Bourbon, at Chartrons, to Monsieur Jacques Bourbon Restan Chez Mr John Pearl, Dublin” [translated from the French]

My son,

I received your letter. It gave me much pleasure since I learned from it that you are doing well. But also I had the displeasure to see that you write no better than last year. Doubtless it is the same with your figures. Besides I learned that you are a great libertine and that you pay no attention to what Mr. Pearl tells you. Watch out what you do. I am writing to him that if you do not return to your duty to give you some good strokes of the rod. So, change your way of doing things & apply yourself well. You have very little time remaining where you are, and so that on your arrival here I might not be heartsick to see you an ignoramus, and then besides you will not be well received. [...]

I am not sending you the book you ask me for. I want you to apply yourself to reading English well and to writing it. As for French, you will have time enough when you are here.

BOURBON

P.S. I am sending you via Captain Dennis an écu of six livres to buy yourself English books because I want you to devote yourself above all to reading.

Truxes: “This is a Frenchman whose son is an apprentice in Dublin, and he’s basically telling the kid to shape up and not waste his time. He’s refusing to send any French reading material and tells him to concentrate on developing his English-language skills instead.

There’s also a letter in which a father’s writing to his daughter because she wants something, and he’s telling her that he can’t quite afford it now but he’ll get it for her later. [She] wants some silk to make a gown, and the father is basically saying, ‘You know this French silk is only fashion, it’s only for show—you should have something more substantial than that.’ What dad doesn’t say that to his daughter, right? The message that comes through is that we’re all part of one thing. We have different knowledge and so we see the world differently, but our emotional structure and our basic humanity is really the same.”