urban design

Lesson Plan

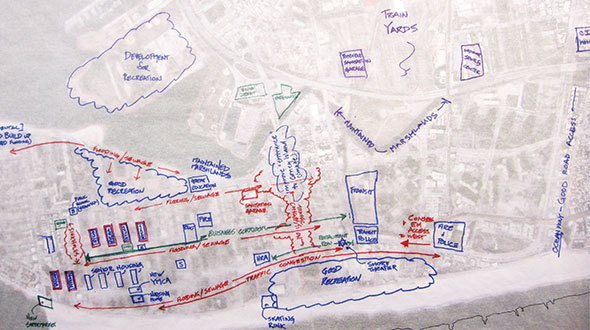

students sketch a strategy for rebuilding coney island

by Alyson Krueger / GSAS ’12

On a wintry Saturday mere months after Hurricane Sandy, when businesses were still shuttered and homes uninhabitable, representatives from the mayor’s office were out at Coney Island distributing hot dogs and hamburgers. The hurricane had washed out the neighborhood’s homes, playgrounds, and shoreline, and soon after, the community had been inundated with well-intentioned outsiders: government officials carrying FEMA forms and volunteers passing out blankets and bottles of water. But this dreary Saturday had also drawn another group of do-gooders—students from NYU’s Schack Institute of Real Estate at the School of Continuing and Professional Studies. They weren’t there to hand out supplies, or even to listen to residents reminisce about easier days. Instead they’d gathered with more than three dozen Coney Island residents—from the owner of the local bodega to students from a high school social studies class—to lead a weeklong workshop on practical steps for rebuilding.

Residents lamented the lack of express trains to Manhattan and how their water supply was vulnerable to contamination. (In January, they were still drinking bottled water.) They also longed for the return of businesses on the boardwalk and more free recreational activities for their bored teenagers. The NYU students took these issues and designed a plan that not only galvanized an anxious community but offered concrete steps for how the neighborhood could be improved in the long run—something government officials didn’t have the luxury to consider so soon after the disaster. “The city was still really focused on what they had to do right [then], which was to get the street cleared, get the cars out that were completely flooded,” notes Richard Barga (SCPS ’13), a student who participated in the workshop.

To its credit, the city listened. “This was one of the first documents of its kind out there in one of the impacted neighborhoods,” says Nate Bliss (SCPS ’09, ’11), a representative from the city’s Economic Development Corporation. “And it’s been among the documents that are influencing the conversation that is ongoing about how to repair the [area].” Bliss was struck by students’ ideas on what to do with Coney Island Creek, an underdeveloped inlet prone to massive flooding: “[This] led to a conversation about what Coney Island Creek is used for, its vulnerability, and how it might be strengthened and become an asset to the community.”

Fresh out of classes on construction management, real estate development, and real estate finance, the students had the skills and knowledge to imagine how the neighborhood could be built better. And they had the right guidance in Corinne Packard, who had previously worked on large redevelopment projects for the city and, for the past three years, has taught a course at Schack on post-catastrophe reconstruction, where students worked on the ground in other distressed places, such as Haiti and Sri Lanka.

“[Students] take this class because they realize they are learning a set of skills that can be applied to real communities in need, as opposed to just learning how to build, you know, office buildings in midtown Manhattan,” Packard explains.

After the success of the winter workshop, Packard paired students with members of NYC’s Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency, the task force that Mayor Michael Bloomberg appointed in December 2012 to prepare the city for natural disasters in the future. Some of the students’ ideas—such as lowering the cost of insurance if buildings complied with resiliency measures in flood-prone areas—appeared in the final report released in mid-June.

Though the class is long over, student Barga says, only half jokingly: “We’re here if [the city] needs more ideas!”