alumni profile

Passing the Ball

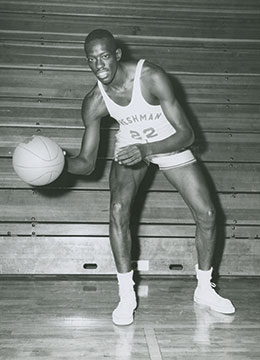

thomas “satch” sanders / stern ’60

by Brian Dalek / GSAS ’10

In the 1950s, the basketball court at Mount Morris Park in Harlem was a second classroom for Tom Sanders. Harlem Renaissance ballplayers such as William “Pop” Gates and John Isaacs eagerly dispensed critiques to the teenager: You think you can play? Can’t cross your feet on defense. Lay some body on him, son. I can come in there at my age and steal the ball from you! Instead of scoffing at them like some other kids, Sanders took the advice seriously. “Always the message was hard,” he says, “but it was to make you better.” The discipline he learned there carved a path toward 13 seasons with the Boston Celtics, a pioneering career in mentoring athletes, and eventually, the Hall of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Sanders, now 74, was nicknamed for his favorite pitcher—Satchel Paige—but this “Satch” was always built for basketball. His game continued to mature, and when colleges started courting him, he found a perfect fit in a program just down the street (Broadway, that is). Because players were red-shirted as freshman back then, Sanders initially focused on school and developing relationships with mentors such as Roscoe Brown Jr.—the WWII fighter pilot who taught at NYU and was founding director of the school’s Institute for Afro-American Affairs. When Sanders finally took the court for NYU, his 6-foot-6 frame and long arms shut down opponents and helped him master a deft low-post hook shot. Over his college career, he scored 1,191 career points and led NYU’s 1960 team to the NCAA Final Four.

Celtics coach Red Auerbach liked what he saw, and drafted Sanders as the eighth overall NBA pick in 1960. His new job description was simple, yet certainly not easy: shut down the likes of Elgin Baylor and Bob Pettit. But he soon flourished as a defensive specialist alongside legends such as Bill Russell, Bob Cousy, and John Havlicek. Sanders says his style matched that of current Los Angeles Laker Metta World Peace (formerly Ron Artest) as an in-your-face forward who could also rebound and knock down an open shot. “To me, [Satch] was the best defensive player of his generation,” says Cal Ramsey, former college teammate and now an assistant coach for NYU. Sanders’ professional career is almost unmatched: eight titles in 13 seasons with Boston—the third-most championships of any player in NBA history.

That may seem hard to top, but when Sanders retired in 1973, some of his greatest accomplishments were still ahead of him. Times were changing, and Sanders noticed that young players needed guidance because, often, “their learning experience was ending in high school.” After becoming the first black Ivy League coach at Harvard University and later, briefly, the head coach of the Celtics, he received a call from Richard Lapchick—son of Original Celtics great Joe Lapchick—who was renowned for his work studying race and gender inequalities in athletics. Lapchick had started a new Center for the Study of Sport in Society at Northeastern University and asked Sanders to come on as associate director in 1985.

Lapchick believed that Sanders could help him focus on developing the amateur athlete and convincing the NCAA to better balance sports with education. “He appreciated those who came before him and often talked about how they helped him in his own development,” Lapchick says. “It was natural for Satch to do the same for the younger generation.”

A few years later, NBA commissioner David Stern took notice of Sanders’ work at Northeastern and spoke with him about creating a Rookie Transition Program. “I looked at the program on paper, and it had a lot of shrinks involved,” Sanders says, but not enough lessons in day-to-day activity. So he started a symposium for newly drafted NBA players with lectures on handling stardom—including media, money, drugs, fans, and life after basketball. For 18 years, Sanders led the NBA Player Programs. In that time, every other major sports league replicated his workshops.

While Sanders still ranks among the all-time winners in NBA history, it’s his work off the court that finally got him inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame as a contributor in 2011. It confirmed that his most enduring influence on the sport may be the thousands of athletes he’s helped to lead more productive lives. Ever humble, Sanders says that his goal was simple: “I wanted to give them an opportunity to grow.”