nonfiction

Coming of Atomic Age

The Young Women Who (Unwittingly) Built The A-Bomb

by Nicole Pezold / GSAS ’04

The only thing Celia Szapka knew as her train rattled along in the August heat of 1943 was that they were headed south. Szapka, a 24-year-old secretary working for the State Department in New York City, had been picked up by limo, taken to Newark Penn Station, and led aboard a berth with several other young women all hired for “The Project.” She had not been told where the job was, whom she’d be working for, what she’d be doing, or how long it would last—only that it paid well and was in service to ending the war.

What waited at the end of this journey was Oak Ridge, a top-secret town raised almost overnight in the mountains of eastern Tennessee as part of the Manhattan Project. Its singular purpose was to enrich as much uranium as quickly as possible for use in the War Department’s quest to develop a nuclear bomb.

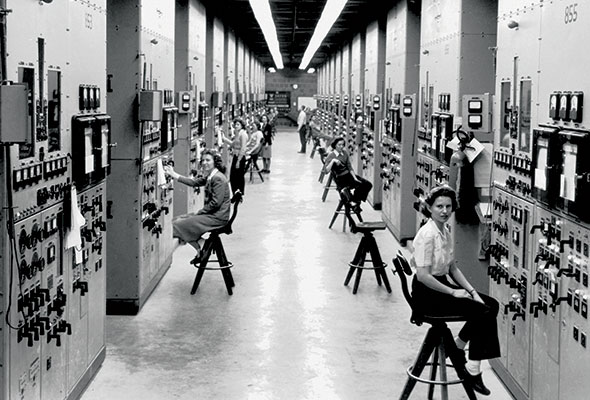

It was an arduous task, and as chronicled in journalist Denise Kiernan’s book, The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II (Touchstone), much of this labor fell to women like Szapka. Kiernan (WSUC ’91, STEINHARDT ’02) presents her story, as a secretary at the town’s administrative headquarters, along with the narratives of women at all levels of this undertaking—including Dorothy Jones, a calutron cubicle operator in one of the processing plants, and Leona Woods, a physicist who helped to create the first sustained nuclear reaction. “The most ambitious war project in military history rested squarely on the shoulders of tens of thousands of ordinary people, many of them young women,” she writes.

Kiernan resurrects this moment in history through hundreds of interviews with former workers, many now in their nineties, and extensive archival research. Since its release last spring, the book has landed on The New York Times best-seller list and has won the attention of critics. The Washington Post called it “fascinating,” noting that “Rosie, it turns out, did much more than drive rivets.” The author was approached by Hollywood when the book was merely in proposal form, and continues to ride a wave of lectures, interviews, and book events, from Raleigh to Milwaukee—including a party in Nashville thrown by one of her subjects, Colleen Rowan, where all the ladies dressed in 1940s military garb and passed around atomic-themed cocktails.

The Project sought out young women like Rowan and Jones, from rural Tennessee and fresh out of high school, because it was thought that they were easier to instruct and asked fewer questions. These were important traits because there was no end to the secrecy once recruits arrived in Oak Ridge. Each was given just the sliver of information necessary to do her job. The word uranium was never spoken or written. Instead, it was referred to as “tubealloy” and “product”—not that anyone but, say, the chemists even knew what uranium was or how its power might be harnessed for this newly discovered thing called fission.

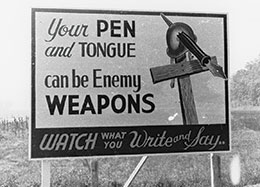

Lest anyone start blabbing about work, residents were bombarded with warnings. There were billboards, editorials, missives, and the occasional, sudden disappearance of a loose-lipped colleague, and these reminders mostly worked. “Nobody wanted to be responsible for derailing the war effort,” Kiernan explains. “If they said, ‘Keep your mouth shut or you’re going to screw things up,’ then it was like, ‘Well, I’ll keep my mouth shut.’ ”

By 1945, Oak Ridge was home to 75,000 workers and their families. The days were long, and the work never stopped for holidays. Housing was scarce and shoddy. Single women were generally assigned to dormitories, while families scrunched into prefab houses and trailers. There were lines for everything—food, cigarettes, books. The mud was ubiquitous and calf-deep. Despite the discomforts, these years marked a formative period for many of the young workers. It was the first time they were on their own, pockets flush with cash, and a lively social scene sprouted instantly. There were dances, religious services, a movie theater, and all manner of clubs, from basketball to Girl Scouts.

You only had to be white to partake in the fun. African-Americans, who were primarily hired to build or clean the town and plants, faced all the indignities of segregation and more. When Kattie Strickland and her husband arrived from Alabama, they discovered that they were not allowed to live together (and unlike white workers, they were barred from bringing their children to Oak Ridge). There was one camp for black men and another for black women, separated by a high fence, barbed wire, and guards. They had a 10 pm curfew and little privacy, with four people squeezed into a one-room hut heated by a coal stove. Cooking in the huts was forbidden. Instead, there was a special blacks-only cafeteria, renowned for serving up mystery meat and “rocks, glass, or some dangerous piece of harmful trash.” After a particularly harrowing bout of food poisoning, Strickland started to surreptitiously bake corn bread, biscuits, and other comfort foods in the huts on rumpled pans fashioned from scrap metal.

Life turned truly horrific for some African-Americans, such as Ebb Cade, a healthy 53-year-old construction worker. When both of his legs were broken in a car accident, doctors at Oak Ridge were ordered not to set them immediately and to give him injections of plutonium to study its effect. Thereafter he was known as HP-12. Staff collected urine, feces, and tissue samples, and removed 15 of his teeth. He died eight years later, reportedly from heart failure. In 1994, President Bill Clinton appointed a special committee to investigate this and thousands of other human radiation experiments that were conducted from 1944 to 1974.

Though Kiernan found many letters of complaint addressed to everyone from construction bosses to President Roosevelt, many black workers stayed on. The simple truth was that African-Americans’ experience in Oak Ridge was not so different from elsewhere in the South and beyond, but the wages could not be matched.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the United States dropped a bomb armed with uranium processed at Oak Ridge on Hiroshima, and another three days later on Nagasaki. Just like that, the world ventured into a new age, the war ended, and a veil was lifted on the true purpose of The Project. It would take some time to understand the full scale of destruction in Japan.

In Oak Ridge, there was jubilation. Everyone could return to faraway homes and know that their brothers, husbands, and sons would soon join them. But a surprising number also settled in right there, taking new jobs in the burgeoning field of atomic energy. Today, the town has only 28,000 residents but is home to the Department of Energy’s largest national laboratory and celebrates its unusual origins each June with the Secret City Festival. “[Oak Ridge] may have been constructed by the government,” Kiernan says, “but they had built that community by staying there, eating there, marrying there, having babies there.”