nonfiction

Writing to the Beat

Devon Powers recalls the dawn of rock criticism

by Kevin Fallon / CAS ’09

These days, a person can tweet a review of Justin Bieber’s new song and have his or her 140-character opinion taken (somewhat) seriously. The reflex is so common that it’s hard to remember it took a revolution to get there.

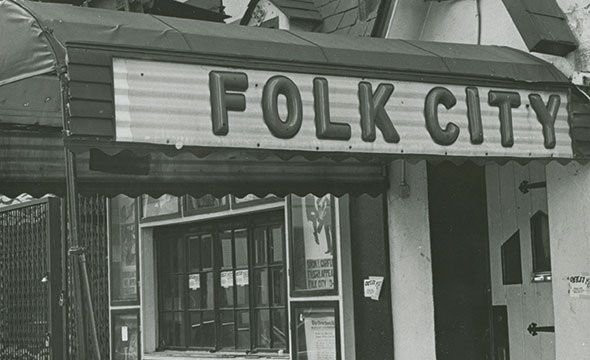

Devon Powers’ book Writing the Record: The Village Voice and the Birth of Rock Criticism (University of Massachusetts Press) chronicles the critical side of that revolution, revisiting the work of a talented, tenacious group of Village Voice journalists in the 1960s and ’70s. These early rock critics, including Richard Goldstein and Robert Christgau, had a simple idea: to write about a cultural movement, you actually have to be a part of it. Newsweek declared in 1966, “Goldstein has created his own journalistic discipline—the ‘pop’ beat,” which allowed him to roam the world of “miniskirts, underground filmmakers, LSD cultists, and rock ’n’ roll musicians.” Along the way, notes Powers (STEINHARDT ’08), an assistant professor of culture and communication at Drexel University, these writers helped to legitimize the study of popular culture itself.

We spoke with Powers to discuss the birth of rock criticism, pop culture in the digital age, and whether the notion that “everyone is a critic” is actually true.

When a person thinks about music critics in the 1960s, they have a romanticized, Almost Famous–inspired idea that they all partied with rock stars. Was it really like that?

I’d say yes and no. Yes, to the extent that rock musicians were a lot more accessible then. I mean, Richard Goldstein has told me stories about meeting Janis Joplin and Diana Ross and all these people. But music writers, they were twentysomethings; they were making really crappy money. It wasn’t wrapped in glamour and fashion. It was an amazing job, but you were still living in a crappy apartment and wondering what you were doing with your life.

Village Voice founder Dan Wolf said that the paper “was conceived to demolish the notion that one needs to be a professional to accomplish something in a field as purportedly technical as journalism.” That seems like déjà vu with blogs and micro music sites doing rock criticism. Is there a difference?

The concerns of the mid-1950s are different. It is an era when people are obsessed with the word conformity. It’s post-nuclear bomb. The oppressiveness that people of an alternative sensibility felt in the ’50s is not the same as what people felt at the rise of blogs and social networking. You might be taking down an establishment, but it’s not The Establishment, capital “T,” capital “E.”

Then what’s the difference between the nonprofessionals he was talking about and this notion that “everyone is a critic,” which sort of dismisses the nonprofessional?

Part of the reason that mainstream journalism was not paying attention to what was going on in the Village is that they didn’t know. By getting people who were local and in the thick of things, [the Voice] could speak more knowledgably about what was happening. The one sort of problem that I have when people say, “everyone is a critic” is that yeah, everyone’s a critic, but not everyone pays attention. I’m going to value what my friend who knows a lot about film says more than Mom—not that my mom isn’t great.