In the fight for marriage equality, it's Edith Windsor vs. the United States of America

by Jill Hamburg Coplan

The relationship that may usher in a new era for gay rights began in a typical way one evening in Greenwich Village. The year was 1963, the restaurant Portofino—a fashionable Friday-night spot for women, and about the only place a white-collar lesbian could be out and at ease. Edith Schlain Windsor (GSAS ’57)—Monroe-esque, cherubic cheeked, and her hair in a perfect flip—was an NYU-trained mathematician and fast-rising IBM programmer, just back from a fellowship at Harvard University. She was tired of being single and past ready to jettison the “therapy” meant to make her straight.Friends brought Thea Clara Spyer to her table. A child of European refugees, Thea was charismatic and intellectual, a psychology PhD from Adelphi University who’d interned at St. Vincent’s Hospital. The angular brunette mesmerized Edie. Thea was more experienced, having been expelled from Sarah Lawrence College for kissing an older woman. And she seemed a bit more comfortable in the Village’s small lesbian underground of bars, run by the Mafia, where even huge bouncers at the doors couldn’t prevent the occasional violent police raid.

They danced.

“We immediately just fit, our bodies fit,” said Thea, in the award-winning 2009 documentary film, Edie and Thea: A Very Long Engagement by Susan Muska and Gréta Olafsdóttir. Their connection was passionate, and they became inseparable. In 1967, Thea proposed with a round diamond pin, because a ring would draw unwanted attention.

“She was beautiful,” Edie said in a recent interview. “It was joyful, and that didn’t go away.”

For more than four decades, they shared life and love in an apartment on Fifth Avenue near Washington Square, where Thea also saw patients. But while straight friends married and raised children, those doors were closed to the couple. IBM rejected Edie’s insurance form naming Thea as beneficiary. Legally, they remained strangers—when Thea was diagnosed, at 45, with multiple sclerosis; when Edie took early retirement and evolved into her full-time caregiver; when they did financial planning. Until 2007. Thea’s doctor said she had only one year left. Thea, by then paralyzed, proposed again.

This time, doors were open. With friends, they flew to Toronto (Canada had enacted marriage equality in 2005), hauling a duffel bag of tools to take apart and reassemble Thea’s giant motorized wheelchair. Edie festooned an airport hotel conference room with palms and white fabric. She wore pastel silk, offset by a burst of fresh white flowers, while Thea chose all black with one red rose. Canada’s first openly gay judge officiated: “You have found joy and meaning together and have chosen to live your lives together,” he intoned. “To this moment you’ve brought the fullness of your hearts and the dreams that bind you together.” When Thea welled up with tears, Edie dabbed them dry. They exchanged wedding bands.

Two years later, Thea was gone. Edie suffered a heart attack in her grief. And then the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), a 1996 federal statute, kicked in, transforming Edie’s story from personal tragedy to public issue. DOMA recognizes marriage as “only a legal union between one man and one woman. ‘Spouse’ refers only to a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or wife.” This definition has consequences far beyond simply barring one group of people from saying “I do.” Married couples, according to the federal tax code, can transfer money or property from spouse to spouse upon death without triggering estate taxes (the “unlimited marital deduction”). But gay couples, after DOMA, have no such rights, even if the marriage is recognized by their state of residence, as Edie and Thea’s was by New York.

So at 80, alone and living on a fixed income with a weakened heart, Edie paid a $363,053 widow’s tax from her retirement savings. And with that payment, Windsor v. United States was born.

There’s more at stake in the case, now before the U.S. District Court in the Southern District of New York, than recovering federal estate taxes, say Edie’s lawyers, Roberta Kaplan of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, and James Esseks, director of the ACLU’s Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender & AIDS Project. Recognition for Edie and Thea’s marriage at that court—or, if it’s appealed, by a higher court, possibly the Supreme Court—would set a precedent that gay and lesbian people have equal protection under the Constitution. It’s impossible to predict whether this will be the case, of several pending nationwide, that the Supreme Court will choose to hear. But it may be. And if it is, Windsor v. United States may shape the future of gay rights in America.

Legally, marriage is about far more than sentiment. It’s one way that government conveys rights and privileges to citizens, including Social Security, inheritance, tax relief, bankruptcy protection, resident status for a spouse who’s a foreign national, parenthood, custody, adoption and property rights, and many others—1,138 benefits in all. By denying such rights to LGBT spouses who are considered legally married in the (now six) states that permit it, DOMA has created a category of second-class citizens, the Windsor complaint argues: “Singling out one class of valid marriages and subjecting them to differential treatment is…in violation of the right of equal protection secured by the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.” There are some 80,000 same-sex married couples in the United States today, the ACLU says.

Along with rights, marriage also confers a different sense of identity. Even after 42 years together, Edie gave a rousing speech at a rally on the steps of City Hall in Manhattan, shortly before Thea died: “Married is a magic word, and it is magic throughout the world. It has to do with our dignity as human beings, to be who we are openly. People see us differently. We heard from hundreds of people, from every stage of our lives, pouring out congratulations. Thea looks at her ring every day and thinks of herself as a member of a special species that can love and couple, ‘until death do us part.’ ” Windsor’s lawyers contend DOMA denigrates Edie and Thea’s “loving, committed relationship that should serve as a model for all couples.”

The Windsor case comes at a momentous time, when marriage equality, and gay rights broadly, have become the civil rights issue, says Patrick Egan, a public-opinion scholar and assistant professor of politics and public policy in the Wilf Family Department of Politics. And 2011, especially, looks to be a turning point. “Historians will probably look back on this year as the moment a majority of Americans came to have the attitude that same-sex marriage should be legal,” Egan says.

Alongside public-opinion shifts, legislative action has been brisk. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (which barred openly gay men and women from serving in the military) was repealed in 2010. In June 2011, New York State approved same-sex marriage, joining Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, and the District of Columbia. In mid-July, President Obama “proudly” announced his support for the Respect for Marriage Act, introduced by Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) and Congressman Jerrold Nadler (D-NY), which would bar the federal government from denying gay and lesbian spouses the same rights and legal protections straight couples receive.

And a judicial development last February was also significant: Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. said that the Justice Department will no longer defend DOMA. (That role, including in the Windsor case, devolves to Republican leaders in Congress.) Holder called parts of DOMA unconstitutional because they violate the equal protection rights enshrined in the Fifth Amendment. There’s no reason, he wrote, to justify treating gay men and lesbians differently from heterosexuals. And he tied the decision directly to Edie: He resolved to make the announcement, he said, after reviewing some “new lawsuits,” specifically naming Windsor’s case.

“The Holder letter was a game changer,” says Kenji Yoshino, Chief Justice Earl Warren Professor of Constitutional Law at NYU School of Law and author of Covering: The Hidden Assault on Our Civil Rights (Random House). “It signals a kind of change in the zeitgeist. While it’s not binding on any federal court, it will be immensely persuasive. The question is whether the Supreme Court accepts that argument or not.” In August, the Department of Justice went even further, directly advising in a brief to the court of the Southern District of New York that Windsor be granted a tax refund because DOMA’s definition of marriage is unconstitutional.

Along with equal protection, there’s another angle to the anti-DOMA cases: states’ rights. As rooted in the 10th Amendment: “The powers not delegated to the United States…are reserved to the States….” When it comes to marriage and family law, the federal government has generally deferred to the states, Constitutional scholar Yoshino explains. DOMA “creates a federal intrusion into a traditional state domain,” he says. Plus, there’s another subtlety at work: Conservatives tend to favor empowering the states, shifting power away from the federal center. So conservative judges, who might not otherwise support gay marriage, could overturn DOMA simply because it overextends the federal hand.

If either the equal protection or states’ rights argument persuades a court to rule likewise, the decision will have far-reaching implications, says Edie’s counsel, the ACLU’s Esseks. Bans on same-sex couples adopting, for example, would need to be reviewed. Anti-LGBT employment discrimination would be hard to justify. Denying health care and pension benefits to same-sex spouses of public employees could be defeated. Ignoring harassment of LGBT students in schools could become illegal. “Every nook and cranny of LGBT rights law will be affected,” Esseks predicts.

Still, these rapid developments unfold against a backdrop of pervasive, sometimes violent discrimination. The FBI reports 1,223 hate-motivated crimes against gay men and lesbians occurred in 2009, the most recent year for which data is available. Only six states allow same-sex marriage; however, these marriages are not recognized in the vast majority of states. Twenty-nine have explicit constitutional bans on same-sex unions while 12 other states have statutes against them. As Rachel Maddow of MSNBC joked, gay-marriage rights “kick in and out like cell phone roaming charges when you cross state lines.” As such, much discrimination remains in employment, housing, public accommodation, and credit. Transgendered people especially lack legal protection.

Edith Windsor was born in Philadelphia in 1929, not long before her family lost their home and business in the Great Depression. She graduated from Temple University with a degree in psychology, was briefly married and divorced, and then moved to New York to start over. She landed in the NYU neighborhood in the early 1950s—her first apartment was on West 11th Street in a third-floor walk-up with a bathroom in the hall. At 23, after a series of dead-end secretarial jobs, she enrolled as a graduate student in math, which had interested her in college, “to find myself in a profession,” as she says.

She also worked for NYU’s math department, entering data into its UNIVAC, the world’s first commercial electronic computer. It occupied an entire floor, weighed eight tons, and performed about 1,900 calculations a second—state of the art in the early ’50s. NYU had one of only a few dozen UNIVACs in the country. The university was also one of six installations of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), and Edie worked on its behalf, loading giant tapes into the computer and creating documents on the department’s mathematical typewriter. One of two or three women in the department, she was eager to advance and soon found work as a programmer at Combustion Engineering, Inc’s facility on West 15th Street, which also relied on the UNIVAC. There she worked with physicists, beginning her shift at midnight, loading tapes and interpreting the information that appeared on the UNIVAC’s tiny screens.

When she wasn’t working or studying, she read literary magazines at the Bagatelle, a lesbian hangout on University Place between East 11th and 12th streets. “When someone walked in who I knew worked at NYU, I was panic struck,” she says. She was especially terrified once to be summoned by the FBI, which had to give her security clearance to work for the AEC. Gay people were being purged from government at the time, yet she determined that she’d tell the truth if asked. She just didn’t want to go to jail. “I found out that impersonating a man was illegal, so I wore crinolines and a marvelous dress to meet the FBI,” she says. Their only concern, she discovered, was her sister’s relationship with a teachers union.

Soon she moved to an apartment on Cornelia Street (rent: $37.50 a month), finished her degree, and got hired at IBM, thanks to connections she’d forged at NYU. Her work involved programming languages and early operating-system software: “I was working on interactivity 25 years before the Internet.”

The start of Edie’s life with Thea was eventful—personally, professionally, and politically. In 1968, flourishing in their careers, they bought a house together in Southampton and a motorcycle custom-painted white. IBM named Edie senior systems programmer, its highest technical title. In June 1969, after a vacation in Italy, they returned home to an eerily tense West Village, with police everywhere. They quickly discovered the Stonewall Inn had erupted in riots the night before.

“Until then I’d always had the feeling—and I know it’s ignorant and unfair—‘I don’t want to be identified with the queens,’ ” Edie admits. “But from that day on, I had this incredible gratitude. They changed my life. They changed my life forever.”

In the years that followed, Edie marched holding a Gay Liberation Front banner, paraded with rainbow flags, and for one Village Halloween Parade, she and Thea loaned their cream-colored Cadillac convertible to a gay-rights group. A giant sign on the back sported their names: “Donated by…,” and seeing it, Edie recalls feeling okay with being so visible: “I said to Thea, ‘It’s a whole new world.’ ”

When IBM moved Edie’s group out of town in 1975, she took a severance package and began a second career as an activist, she says, “for just about every gay organization that existed then or was being formed.” She manned the telephone tree for Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders, computerized the mailing lists for the East End Gay Organization, and helped to found Old Queers Acting Up, an improv group whose skits tackled ageism, racism, and homophobia with the rallying cry “out of the closet, onto the stage.” She persevered as the atmosphere downtown evolved from the free-love ’70s to the “Silence=Death” militancy of the ’80s AIDS epidemic. When New York City established a domestic-partner registry in 1993, she and Thea were No. 80 in line. But her real sense of community blossomed, she says, when in 1986 she joined the board of Services & Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE), which serves 2,500 seniors a month in New York City and has 23 affiliates nationwide.

Gay and lesbian seniors’ lives have been so circumscribed compared to the lives of the young that SAGE’s mission of creating community is especially powerful and poignant. Denied the right to raise legally recognized families, and often shunned by their siblings, many LGBT adults of Edie’s generation live in isolation—one reason that Mayor Michael Bloomberg and SAGE in 2011 announced a new city-funded LGBT senior center for the Chelsea neighborhood. While being alone isn’t uncommon among the elderly, “aging without family support is far more profound in our community,” says Catherine Thurston, SAGE’s senior director of programs. “The majority of folks we work with do not have adult children.”

Caring for Thea dominated Edie’s last years with her, when preparation for bed might take an hour and getting set to roll in the morning three or four. Marriage equality at the end of life is a little-noted but key aspect of the Windsor case. Without a recognized marriage, a same-sex spouse could, for example, despite a lifetime shared, be forbidden from writing an epitaph or arranging a funeral.

Last November, SAGE honored Edie with its lifetime achievement award. This year, she was also honored by Marriage Equality New York, received the City Council award at its Gay Pride celebration, and, with her attorneys, received the ACLU Medal of Liberty. The exhausting, exciting season ended at a press conference in Washington, D.C., helping Sen. Feinstein and Rep. Nadler introduce the Respect for Marriage Act. Edie spoke at the Rayburn House Office Building, visibly moving the gathered crowd with her story.

“Spending the day with Edie in Washington is like spending a day with Mick Jagger,” attorney Kaplan says. “A Congressional aide told her she was the Rosa Parks of our generation.”

Edie recounted her season making history in the cozy galley kitchen of her Southampton home, painted white and decorated country casual. Straw hats hung on the wall, wicker baskets sat on wide-plank floors, and a glass jar of granola was set on the counter. On her bookshelf, recordings of Schubert, Beethoven, and Haydn shared space with workout tapes and a home-repair manual. In a crisp pink oxford shirt, Gucci belt, fuchsia nail polish, and black jeans—and still that perfect blonde flip—Edie dispensed hugs, even to a visiting reporter, along with coffee and croissants. A pair of young children, offspring of the one dear cousin she says always accepted her, read by the pool. Later they were to see the latest Harry Potter film, and Edie would visit with City Council Speaker Christine Quinn.

The case still has her pinching herself, she says, and wishing Thea could share in it.

“We never dreamed it,” Edie reflects. “We didn’t expect marriage, even 10 years ago, and I never expected I’d be looking at a piece of paper that said ‘Windsor versus the United States of America.’ Fighting is very hard—we spend our lives coming out, in different circumstances. We’re never all out, somehow. It takes a lot of guts to stand up and let people know—people you’ve lied to much of your life—that not only are you a lesbian, but you’re a lesbian fighting the United States of America.”

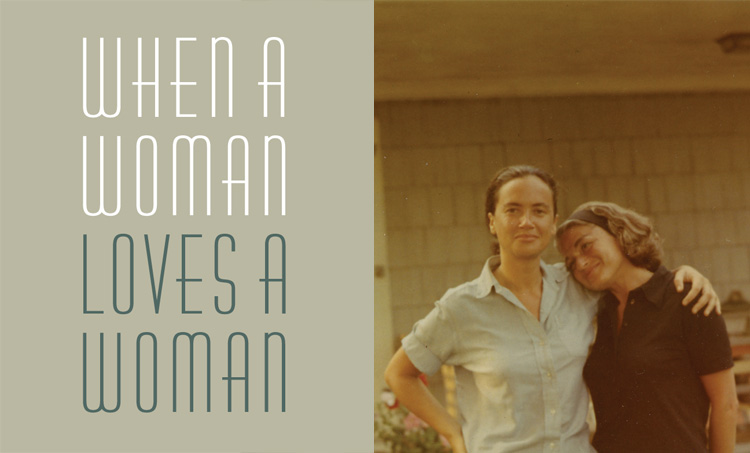

Edith Windsor (right) and Thea Clara Spyer met in New York City in 1963 and, though not legally allowed to marry until 2007, were a devoted couple for more than four decades.