Former Life photographer Bob Gomel reflects on the many American stories told with his camera

by Andrea Crawford

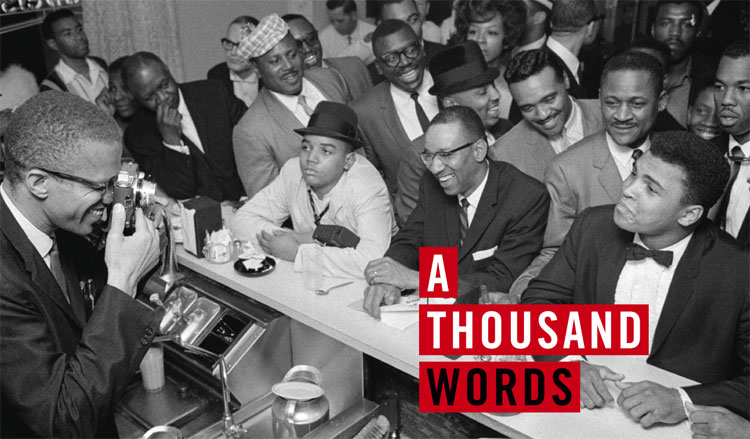

A brash 22-year-old dancing around the ring, his gloved fists raised in victory as he proclaims himself “the king of the world”: This may be the most famous image of Muhammad Ali when he was still Cassius Clay—and had just defeated heavyweight champion Sonny Liston in one of boxing’s most stunning upsets. Bob Gomel was there shooting photos for Life magazine, having journeyed to Miami Beach in February 1964 to shadow Clay in the days leading up to the bout. But it was an image Gomel (STERN ’55) captured during the afterparty—of Malcolm X snapping a photo of the new world champion—that the Library of Congress deemed worthy of acquiring last year. From behind the bar, the former Nation of Islam spokesperson smiles broadly as he holds the camera to his face. The seated Clay wears a tuxedo and bow tie, his hands resting in loose fists on the counter. He appears to mug for the camera.It’s a moment of connection between friends, revealing a playful side of two powerful men whose public personas were often serious, angry, or in Clay’s case, downright crazy. The photograph also bares a secret between them: The boxer had been persuaded by promoters not to announce his conversion to Islam before the fight. The following day, he would make the announcement to the world.

Getting behind the scenes and using photographs to tell a story was what Life did best, and it was what attracted Gomel to the picture magazines. As a young man, he turned down other journalism jobs and went without work for nearly a year waiting to break in. When the chance came, Gomel made the most of it. From 1959 to 1969—the magazine’s last decade as the country’s premier newsweekly—he photographed a long, impressive list of world leaders (John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Nikita Khrushchev, Patrice Lumumba, David Ben-Gurion, Jawaharlal Nehru), actors (Marilyn Monroe, Warren Beatty, Joan Crawford), athletes (Arthur Ashe, Willie Mays, Sandy Koufax, Arnold Palmer, Joe Namath), and other personalities of the era (Jane Jacobs, Robert Moses, Benjamin Spock). When President-elect Kennedy took a walk with 3-year-old Caroline on the day her brother, John Jr., was born; when Martin Luther King Jr. gave his speech at the March on Washington; when the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show; Gomel captured it all on film.

Like any enduring image, says Ben Breard, who featured many of Gomel’s works in an exhibition earlier this year at Afterimage Gallery in Dallas, the photographs are important not only because of their historical and cultural significance. “Of course, there’s an element of being at the right place at the right time to capture the moment, but then you’ve got to do it artistically,” Breard says. The images reveal the photographer’s sense of humor and humanity. “There’s a positive feel to his work,” Breard adds. “It’s uplifting. Even though those were hard times the country went through, [there’s] a hopeful aspect to everything.”

Born in Manhattan and raised in the Bronx, Gomel discovered photography as a boy, struck by an image taken by his teacher hanging in his classroom at the Ethical Culture School on Central Park West. It was a black-and-white picture of a manhole cover on a cobblestone street with some pigeons around it. “I sat next to that picture, and I was just entranced by it,” he says. Gomel joined the teacher’s photography club and began learning on a borrowed camera. When World War II ended, he got a job delivering groceries by bicycle to buy his first camera and soon convinced his parents—his father was an optometrist; his mother, an NYU graduate, was a teacher—to let him appropriate a closet for his darkroom.

When Gomel arrived at his mother’s alma mater in 1950, he began working for student publications, covering basketball games, which NYU then played at Madison Square Garden. There, he befriended “the fellows who worked the night shift” for the Daily Mirror, the Daily News, the Associated Press, and UPI (then called ACME Newspictures), and he started tagging along on their assignments. After graduating from NYU and serving four years in the U.S. Navy, he was promptly offered a job at the Associated Press. But by then, he had changed his mind about what he wanted to do. “I just felt one picture wasn’t sufficient to tell a story,” he explains. “I was interested in exploring something in depth. And, of course, the mecca was Life magazine.” He turned down the offer from AP.

At Life he was able to shoot the stories that appealed to him, and the recent exhibition included some of his favorites. For one photo-essay, he documented what happens to the family dog when the children return to school, highlighting one forlorn basset hound, in particular. For another series, he arranged for humorist Art Buchwald to go back to Marine boot camp incognito for a week, to relive his days as a recruit. The humor and power of these images endure, even for those too young to know Art Buchwald.

Gomel, who later worked in advertising shooting national campaigns for clients such as Volkswagen, Pan Am, Merrill Lynch, and Shell Oil, also tested technological and creative boundaries at Life. His image of the Manhattan skyline during a blackout in November 1965 is striking, with a full moon illuminating the dark sky. But from his vantage point on the Brooklyn waterfront that night, the moon was behind him. “It occurred to me that the only way we’re all getting along this evening is because we have a full moon,” he says. “I wanted to tell that…in a single picture.” So he rewound his film, changed lenses, turned around and clicked, placing the glowing orb just where he wanted it to be in the dark quadrant of the frame. After a long debate, Gomel says, the editors decided to run it—the first double-exposure Life used in a news story.

Gomel believes photographers have the responsibility to be truthful reporters but also must be clear about what story they’re trying to tell. “Photography is all about having something to say before you pick the camera up to your eye and push the button,” he says. “Are you happy about something, displeased about something? And if so, how are you going to express that on a piece of film?”