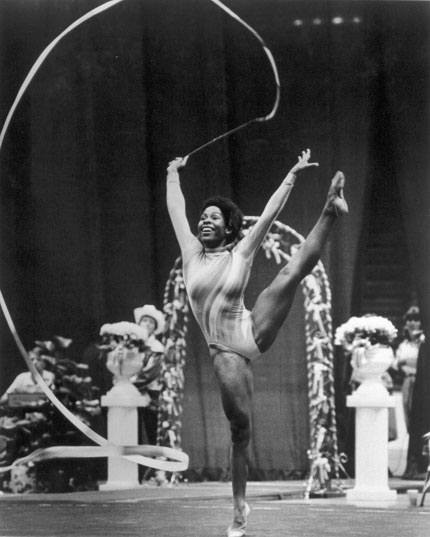

alumni profile

Gymnastics for the People

Wendy Hilliard / GAL ’88

by Courtney E. Martin / GAL ’04

In the early 1970s, Wendy Hilliard sat cross-legged on the living room floor, transfixed by the compact Russian women leaping across the TV screen. At age 12 and the youngest of four girls in a middle-class African-American family in Detroit, she had next to nothing in common with these gymnasts. But the determination was already flooding her face. “That’s what I want to do!” she yelled to her mother who, after some research and penny-pinching, found a gym for her daughter out in the suburbs, because there was no equivalent in the city then. When Hilliard came home from her first practice, she told her father, “Daddy, daddy, I’m going to do rhythmic gymnastics!” He replied, “That’s great, baby. What’s rhythmic gymnastics?”

His unfamiliarity was not surprising. Gymnastics has long been a sport of the wealthy and white, thanks to the high price tag of training and traveling to competitions. Rhythmic gymnastics, which involves twirling ribbons and dancing with balls and hoops, requires even more specialized training. Hilliard, who went on to become the first African-American to represent the United States in rhythmic gymnastics in 1978, is changing all that. In 1996, she founded the Wendy Hilliard Foundation to give girls and boys from low-income neighborhoods the opportunity to participate in gymnastics and, more broadly, learn the indispensable life lessons therein. “There’s nothing like gymnastics for teaching self-discipline and determination,” Hilliard explains, reminiscing about the thousands of hours she spent in the gym under the stern eyes of Vladimir and Zina Mironov, the Russian husband-and-wife team who nurtured her early on.

Hilliard’s foundation has now served more than 10,000 young people through free weekly gymnastics classes, summer camps, literacy and nutrition workshops, competitive rhythmic gymnastics scholarships, and annual girls’ and women’s sports clinics. Indeed, being a mentor and ambassador comes naturally to the former international gold medalist, who was inducted into the USA Gymnastics Hall of Fame in 2008. Since retiring from competition, she’s helmed various organizations in the gymnastics world, and from 1995 until 1997 led the Women’s Sports Foundation as its first African-American president. She also recently helped to design a 15,000-square-foot gymnastics center for Aviator Sports and Recreation, a new multimillion-dollar, multi-sports complex in the Marine Park section of Brooklyn.

Hilliard’s next big dream is to find a permanent gym for her foundation, which currently operates out of a small office in Harlem and relies on a constellation of public facilities and gyms to host its programming. It won’t be easy in these economic times, in this crowded city, but Hilliard recalls the philosophy of her late, much-loved coach Zina on gymnastics and life: “It’s hard, but hard isn’t bad.”

Hilliard has clearly passed this wisdom to her own students, some of whom are now competing at the highest national levels. At 14, Alexis Page is one of the most talented gymnasts to come out of the program and is considered an Olympic hopeful. Her training—four hours daily—costs upward of $25,000 a year, almost all of it supported by the foundation (especially since her mother lost her job). But it’s not just money that Page gets. “Wendy believes that anything is possible,” the young gymnast says. “She’s taught me that if I work hard, rewards will inevitably follow.”

But Hilliard isn’t all hard work. On a recent Saturday at Riverbank State Park in Upper Manhattan, Hilliard was surrounded by a large circle of children wearing stretchy pants and goofy smiles as they jumped and squirmed indiscriminately. Hilliard’s eyes twinkled mischievously as she shouted “T!” The kids suddenly froze in unison, their arms stretched out from their sides. “I!” Hilliard shouted next, and a hundred tiny arms shot up to the sky.