Inside a temple of the Yezidi, one of many minority cultures in the crosshairs of state and religious violence in Kurdistan.

A young writer visits an ancient people at the center of a modern civil war

by Jarett Kobek / GAL ’02

At the end of April 2009, I found myself in the backseat of a car crossing the Turkish border into Northern Iraq. Sitting beside the driver was my guide, a Turkish Kurd who’d nicknamed himself Montana. After a few minutes beneath the fluorescent lights of border control, we joined a long line of cars idling on a bridge over the Khabur River waiting to obtain our Iraqi entry visas. We spent the night in a border town, rising early the next morning and driving south until we reached the mouth of a crumbling asphalt road about 30 miles north of Mosul. It was guarded by two men in a ramshackle shelter with a single assault rifle resting between them. They spoke briefly with Montana and waved us through. Soon we were inside the valley of Lalish, the religious epicenter of an ancient people called the Yezidi. I had journeyed here for one reason: to see them before they disappear.

Like Iraq’s other minorities, the Yezidi are exactly the kind of people for whom the ideal of Operation Iraqi Freedom held the most promise—a group long persecuted for their religious beliefs welcomed into the fabric of a newly “pluralistic” society. Reality has worked out differently. In the seven years since the American-led invasion, the Yezidi have suffered relentless violence and are presently caught in the middle of territorial disputes between the central Iraqi government and Northern Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government. The Kurdish director of Yezidi affairs told The New York Times in 2007 that of a population estimated between 200,000 and 500,000, more than 70,000 have fled into exile. “It’s very grim,” said Samer Muscati, co-author of the Human Rights Watch’s On Vulnerable Ground, a recent report on minority communities in Iraq. “If the pressures they face continue and the Yezidi keep fleeing the country, the future looks bleak.”

My father is a Turkish Muslim turned New Ager. My mother is Irish-American and raised me Catholic. This upbringing left me fascinated by those who elude easy categorization. So when I read about the Yezidi—whose practices resemble a spiritual pastiche with traces of Sufism, the mystical strain of Islam, as well as the ancient Persian religion Zoroastrianism and Kurdish folk belief—I was rapt. Yezidism holds that God created seven angels, chief among them Melek Ta’us, the Peacock Angel, who in turn created the world and is the source of all beauty and good.

But for almost as long as there have been Yezidi, their culture has been misinterpreted by neighboring Muslims, who identify Melek Ta’us as Iblis, the Islamic Satan. Muslims believe the Yezidi worship the devil.

This has fueled centuries of persecution that reached a new height under Saddam Hussein. Throughout the late 1970s and ’80s, Hussein’s government subjected the Yezidi to “Arabization.” They were forcibly relocated and held in collective “villages” to cultivate their dependence on the state. Post-Hussein, the 2005 Iraqi Constitution granted Kurdish self-rule but avoided establishing borders. This has stoked tension between the Kurdistan Regional Government and central Iraq. Most discussion has focused on control of the oil-rich Kirkuk region, but the area that encompasses Lalish is equally contentious. Both the Arab and Kurdish governments claim this land as their own.

While these authorities wrestle for control, the Yezidi have come to know increasingly severe sectarian violence. The worst incident occurred on August 14, 2007, when four coordinated truck bombs exploded in two Yezidi villages, killing at least 500 people and wounding more than 1,500. It was the second deadliest terrorist attack in world history after 9/11. “Under Hussein, the establishment regarded Yezidis as the most expendable Kurds, who could be ill-treated without fear of public protest,” said Philip G. Kreyenbroek, director of the Institute of Iranian Studies at University of Göttingen, Germany, and one of a few scholars who has published widely on the Yezidi. “The new enemy, the Islamists, are driven by a more active hatred and have proved themselves capable of even greater horrors.”

The attack, along with two smaller incidents earlier that year, is widely believed to be part of a wave of radical Sunni Arab violence sparked, at least in part, in retaliation for the honor killing of a 17-year-old Yezidi girl, Du’a Khalil Aswad, who was reportedly dating a Sunni and may have converted to Islam. In April 2007, she was stoned to death by men from her family and Yezidi religious hard-liners. The incident was caught on video and prompted both Amnesty International and Sunni extremists to demand justice.

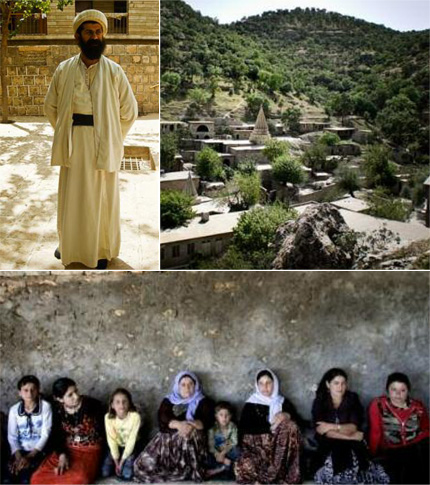

All of Lalish is considered sacred ground; a line of stone blocks prevents vehicles from entering the main portion of the valley, a moderately sized dale surrounded by rocky, scrub-spotted mountains. Other than the few people charged with upkeep and security, Lalish has no residents. It is a place purely for religious pilgrimage.

Lalish’s most distinctive feature is a set of three fluted, conical spires that rise high into the air and mark the Yezidis’ holiest site, the sanctuary and tomb of Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir. The historical origin of the Yezidi dates to the 11th century, when Adi arrived with the intention of founding the Adawiyya Sufi order. The central mystery of the early years is how a Sufi order morphed into Yezidism.

Several men greeted us at the walled entrance to the sanctuary. They led us into a courtyard and asked that we remove our shoes and socks, as custom prohibits footwear in the valley. We were then ushered into a modern room where tea was served. Among the men was Baba Sheikh, the current spiritual leader of the Yezidi. He was tall, with a long black beard, and was dressed in white robes. With Montana translating in Kurdish, I asked Baba Sheikh about Yezidism. He emphasized a belief in one God and focused on the core conviction that the Yezidi are the oldest people on Earth and descended solely from Adam. After Baba Sheikh finished, Montana, who is Muslim, turned to me and said, “I think he is afraid to say they worship the devil.”

We then toured Adi’s tomb. Inside, a long lamp-lit hallway contains an altar and a small spring-fed well, with whose water all Yezidi are expected to be baptized. The hall opens into the tomb of Sheikh Hasan, another Yezidi saint, which leads underground to the valley’s second sacred spring, one of the few places barred from nonbelievers. Past Hasan’s tomb, we entered the room of Sheikh Adi. Adi’s tomb stands against one wall of the room and is decorated in devotional cloths of many colors. The largest of Lalish’s spires serves as the ceiling.

We wandered freely through the rest of the valley, moving in and out of its many shrines. Scattered throughout were sacred spots carved into the stone where olive oil is ritually burned. I was told that there are 365 such spots, one for every day of the year. When we returned to the reception room, Baba Sheikh was still holding court. A voice in English asked, “Would you like me to take you up the mountain?”

This belonged to Mirza Dinnayi, a Yezidi who once served as an adviser on minority affairs to Jalal Talabani, president of Iraq’s central government. Dinnayi had resigned in protest over perceived inaction on minority issues and exiled himself to Germany. He’d returned with several German scholars, who accompanied us up the mountain. As we walked, Dinnayi gave me his version of Yezidism. The gist was the same as what I’d heard before, but he emphasized its sun worship and relationship to Mithraism, a mysterious cult popular with Roman soldiers. It seemed slightly different than what Baba Sheikh described.

This was true of every conversation I had about Yezidism, which is best understood as a religious culture rather than a doctrinal religion. Being Yezidi is a matter of birth rather than faith. There are no converts. There is no written scripture, no book of rules. It is, and has been, a shifting oral culture passed down through families—and like any oral culture, it hosts contradictory ideas. Everything is a matter of debate, even the meaning of Lalish’s rituals.

As we reached the top of the mountain, I could see out over Lalish’s spires. The valley appeared pristine, peaceful. I asked Dinnayi how he envisioned the future. “I am not very optimistic,” he said flatly. “With the Islamisation of society, there is a weekly exodus of 50 Yezidi from Iraq. The Kurdish government actively encourages anti-Yezidi policies, moving Muslims into Yezidi towns.”

Although sectarian violence remains an enormous challenge, the greatest threat to the Yezidi may be the land disagreement between the Kurds and Baghdad. The Kurdistan Regional Government passed a draft constitution last summer claiming large swaths of the disputed territories, prompting Vice President Joe Biden to visit the region in an attempt to calm the situation. A recent report by Human Rights Watch warns the conflict has grown dire enough that it “risks creating another full-blown human rights catastrophe for the small minority communities” caught in the crossfire. By virtue of location, the Yezidi are on the frontline.

As I left Lalish, it was hard not to feel a sense of futility. Life under Saddam Hussein had been brutal for the Yezidi, but life since has been equally, if not more, blood-soaked. My mind wandered back to a moment as we sat drinking tea with Baba Sheikh. A piercing wail erupted from the courtyard. Emotion rippled through the room. In the end, it was only that a bee had stung a child. But the shriek had revealed something in the faces of the men beside me: fear.

Being Yezidi is a matter of birth rather than faith. There are no converts.