Unraveling artist Maira Kalman’s favorite things

by Jason Hollander / GAL ’07

Maira Kalman headed to JFK last May and boarded a flight to Dublin. Like most people on holiday, she was full of verve, and some jitters.After a few days of sightseeing in the capital city, she drove for several hours on winding roads to reach her real destination: a Gothic-style castle located along Ireland’s green and mountainous southern coast. It’s a place where any tourist could indulge, wandering in the cultivated gardens or lounging in the drawing room, awaiting afternoon tea and scones.

Kalman did neither. She had come, at age 62, to spend nine days inside the castle working as a maid. Working. Polishing, pressing, sweeping, scraping, straightening, scrubbing, dusting, and degreasing.

It’s not typically the occupation of an artist who draws covers for The New Yorker, designs products for Kate Spade and Isaac Mizrahi, had a New York Times column, helped create album covers for the Talking Heads, was a guest on The Colbert Report, exhibits her work across the globe, and has illustrated or authored 22 books, including The Principles of Uncertainty, And the Pursuit of Happiness, Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, Michael Pollan’s Food Rules, and Lemony Snicket’s 13 Words.

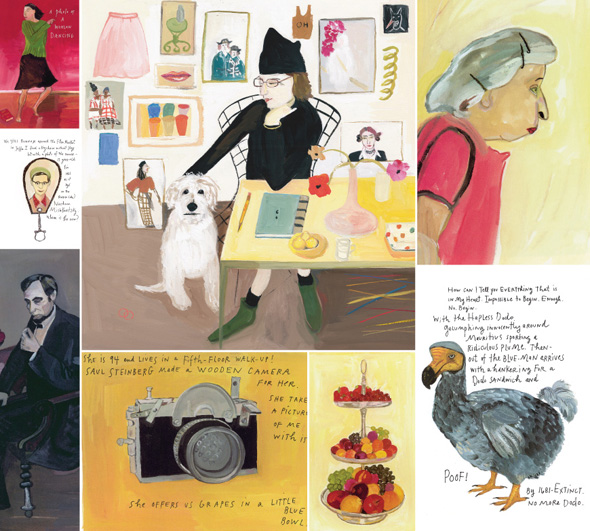

But don’t be fooled—her employment wasn’t a publicity stunt or research for a new book. It was, rather, fulfillment of a childhood dream. “I love objects, and I love taking care of objects,” explains Kalman (WSC non-grad alum), who bunked in the former butler’s quarters. “I love to iron and make things neat and put them in order. It’s an occupation of a very honorable sort.”

Castles are indeed grand places, but they require massive upkeep. And inherent in all the effort to produce all the splendor is a grace that few people on the planet appreciate more than Maira Kalman.

Kalman was born in Tel Aviv in 1949, when Israel was still brand-new. Many of the earliest citizens—including her father—were among the last of their family, the rest having been wiped away by the Holocaust. Those narratives were everywhere then, and being surrounded by them colored her thinking. “The idea that things can be destroyed in a heartbeat,” she says, “that really insinuates itself into your being.”

She moved with her family at the age of 4 and settled in Riverdale in the Bronx, quickly becoming a city kid. Her parents, especially her mother, Sara, impressed on her the courage to embrace New York without self-consciousness or fear. This also applied to any friends, clothes, hairstyles, hobbies, or music she was drawn to. “To use the term unconditional love, that’s something very extraordinary,” says Kalman of her mother. “But she had that.” And so Kalman discovered lifelong enchantments with aimless walks, and objects of character (a tired rubber band, a noble matchbook), and Lewis Carroll, and J.S. Bach, and sponge cake, and the smell of fresh citrus, and Kay Thompson, and Henri Matisse, and then, intensely, the works of Vladimir Nabokov.

It was the Russian author—and his autobiography Speak, Memory—who whispered into her a desire to write. She studied literature at NYU for several years before dropping out in 1971, with no judgment from her parents. They trusted her, even though she was only a handful of classes short of graduating. Things were radical then. “We thought we were going to do something ‘other,’ and a degree wasn’t going to mean anything,” Kalman says. “It turned out to be true for us but, you know, that’s taking a leap.” Part of the “us” refers to her late husband, Tibor Kalman, the legendary graphic designer and founder of the pioneering M&Co, which the two ran until his death in 1999, at 49, of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Tibor provided inspiration after college when Maira, frustrated with her writing, started to put ideas on paper in a new way. She found that shapes and colors were so much more freeing than typed words. And she waded in with no formal training: “I needed to find out who I was without really knowing how to do it.”

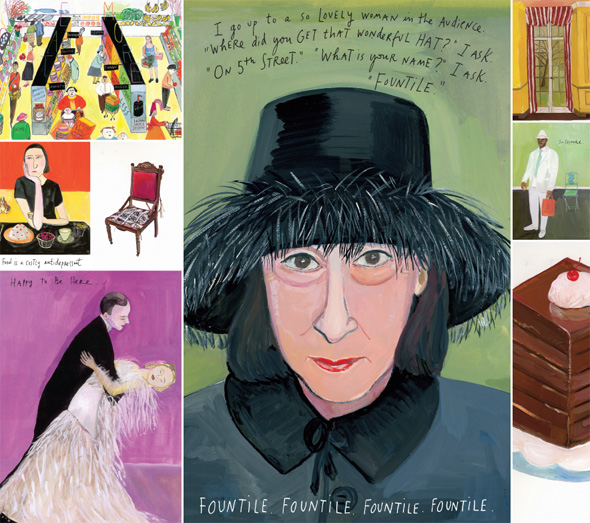

Finding that meant tapping into her earliest lessons of perception. Life as a child with her mother, Kalman says, often felt “free-floating and dreamlike” as they made their way around the city, attuned to the smallest details one could see and hear. “The real world felt completely—and still does—like the unreal world,” she explains. “It wasn’t that she was crazy, it was just this ability to focus on something else.” Kalman channeled that into her art and the words she handwrites as a sort of narration. So the red-footed pigeon on the Avenue U subway platform struts proudly as a man shoos it with his newspaper. The painting of young Nabokov staring so innocently at the reader carries the lament that his life will be forever in upheaval once his family flees Russia. The portrait of a poor-postured, slow-stepping old woman contains a note from Kalman: “Soon enough it will be me struggling (valiantly?) to walk… How are we all so brave as to take step after step? Day after day?”

Others that get the royal treatment include fruit platters, balls of string, curbside couches, radiators, garbage cans, a bathroom sink that “speaks the truth,” and a “tough-as-nails” waitress slicing giant radishes. Yet Kalman also loves fine things—indulgent, delicious, paper-wrapped, fragrant, frilly, bursting-with-color things. She’s drawn to the energy that goes into them, and the sad notion of how quickly they may become part of the weekly trash. To describe her illustration almost demands that you use the word “whimsical,” but there are too many layers for an explanation so simple. The loss of her father (in 1994) and her mother (in 2004), and Tibor, and so many others is inherently tied to her personal works, where even the sparest pictures can feel like collages of memory and emotion. She often weaves in her ever-present fear of death. But the next page usually offers the happiness of fresh yellow and red flowers or a tall slice of chocolate cake.

She’s almost always at work, and prefers it that way. In fact, aside from strolling the city and being with loved ones—especially her daughter, Lulu, who is an executive sous chef for Danny Meyer’s Union Square Events, and her filmmaker son, Alexander—Kalman is happiest when she has a project of some kind. This includes the time she was assigned to scrub the toilets at a Zen monastery she went to for her 50th birthday, an experience—just like her stint in the Irish castle—she calls “hilarious and fabulous and not horrible at all.” It’s just the sort of real-life moment that finds its way into her art, and encompasses all she’s been trying to communicate. “I would love to be able to say that the body of work I have speaks of someone who is very human and has a sense of the joy in life and the beauty,” she says, “and who is heartbroken some of the time.”

Maira Kalman’s next show opens May 10 at the Julie Saul Gallery in Chelsea (www.saulgallery.com).

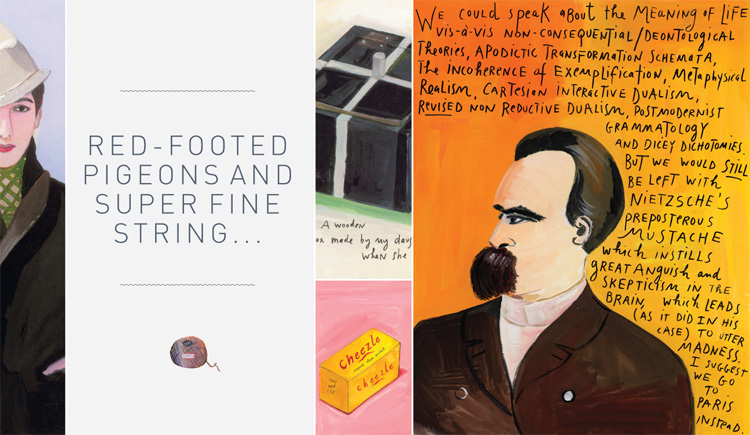

ABove (LEFT): Kalman’s son, Alexander.

Above (MIDDLE): A wooden box made by Kalman’s daughter, Lulu, when she was little (top); Cheezle cheese product (bottom). Above (RIGHT): Some thoughts on Friedrich Nietzche’s philosophy—and moustache.