Research has brought us closer than ever to understanding—and ending—homelessness. The elusive first step is housing.

by Nicole Pezold / GSAS ’04

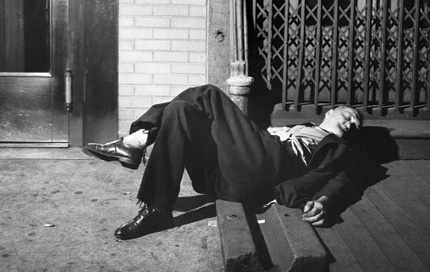

For much of its existence, the Bowery was the ultimate skid row. The mile-long strip in Lower Manhattan, just a few minutes walk from Washington Square, devolved from a raucous shopping and entertainment district in the mid-1800s to a den of 10-cent-a-night flophouses by that century’s end. Men—and it was usually only men—languished in doorways and along the cracked pavement, hassling passersby for change. They smelled of drink, sweat, and often urine or feces, as their lodging rarely had adequate washing facilities, if any. As the rest of the world marched on in the 20th century, little changed there. “It was sad and scary,” says Beth Weitzman, vice dean of the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, who recalls driving through the Bowery as a child in the 1960s. “It was dramatically different from anything one would encounter anywhere else in New York at that time.”Only two decades later, the specter of “street people” would creep out of the Bowery and into neighborhoods across the city. Vagrants could be found sprawled on the stoops of the Upper West Side. Squeegee-men camped out at intersections across Midtown. Panhandlers roamed the subways and public squares. A problem that had once seemed quarantined was suddenly—and literally—on New Yorkers’ doorsteps.

The early-1980s recession saw the number of homeless in the city’s shelters essentially double to more than 28,000 people on any given night. Adding to the alarm, women and children accounted for much of this new business. From 1982 to 1992, the number of homeless families in the city increased by 500 percent. “They likened it to a funnel,” says Weitzman, who was among a team of researchers contracted by the New York City Human Resources Administration to study the crisis in 1988. “The number of families coming into the system was much greater than the numbers [the city] was able to get out.”

Fast-forward to today, and the Bowery, like much of the rest of New York, presents a shinier face. The Bowery Mission still ministers to the down and out, but it’s now flanked by the gleaming hulk of the New Museum, and is neighbor to a Whole Foods Market and $625-a-night suites at the Bowery Hotel. But don’t be mislead: The number of homeless people in the five boroughs has climbed to an historic high not seen since the Great Depression, when the tents of “Hoovervilles” dotted Central Park. On any given night, more than 40,000 New Yorkers—including nearly 17,000 children—will sleep in a shelter, and another 2,000 to 3,000 people will sleep right on the street, according to the Coalition for the Homeless. That’s a population larger than the entire city of Burlington, Vermont. And the rest of the country is faring no better, with possibly two million—or the whole population of Houston—homeless at some point during any given year.

And yet, in many ways, this is a heady time in the struggle to house our fellow citizens. After more than two decades of rigorous study—much of it based at NYU, thanks to the university’s proximity to the original “epicenter” of American homelessness—the problem is no longer an enigma. Research has revealed that our old assumptions, namely that addiction or mental illness lead to homelessness, are inaccurate. Instead the most common denominator is, quite simply, extreme poverty. And the fix, also quite simply, is housing. The challenge now is how to channel the considerable resources that we spend toward the most promising solutions.

This year, New York City has budgeted about $788 million for homeless services. However, the true bill is harder to calculate because of the volatile nature of the problem itself. “Families don’t just go from their own apartment into a shelter,” explains Mary McKay, McSilver Professor of Poverty Studies and director of the new McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy and Research at the Silver School of Social Work. “They tend to move in with relatives or friends first, or go from apartment to apartment, so that by the time they get to a shelter, they’ve been on quite a destabilizing journey.” The descent is so insidious that it taxes every public good, from hospitals and schools to parks and police precincts.

Until researchers turned a critical eye to the crisis in the 1980s, most studies of the homeless had been descriptive—what did they look or act like and how many were we dealing with. They also tended to oversample the “chronically homeless,” those who suffer from severe psychiatric problems, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, and addiction. These are perhaps the most visible of the homeless—the “Bowery types” who set up house on subway grates or have memorized the hours at the church’s basement soup kitchen.

Weitzman and her colleagues wondered whether the families seeking shelter in the late ’80s were beset by the same problems. In 1988, as part of their study for the city, they interviewed more than 550 families on welfare, half of whom sought shelter, to see whether psychiatric disorders or substance abuse caused homelessness. They found that neither was a factor for the vast majority; something else was going on. Five years later, in a study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, they followed up with the same families. By then, four-fifths of respondents had their own apartment, and three-fifths had been there for at least a year—the average being three years. Homelessness, they discovered, was not a permanent state. People were capable of moving on, and what had made the greatest impact was subsidized housing.

“Whereas there had been much more of a tilt toward emphasizing the individual’s deficits, we, among others, helped to shift the lens to say, ‘Wait a second, this is probably more about the fact that poor people can’t get housing,’ ” Weitzman says. In the 1990s, study after study confirmed that while an addiction or illness or domestic violence may hasten the descent into homelessness, or aggravate the climb out, it was not the cause. A man of means, after all, may run a media empire and still abuse prescription painkillers. A mother with a supportive family may get laid off or leave her partner without necessarily losing her home.

History confirms this idea that homelessness is tied to economics. Though we did not officially start counting the homeless until the 1970 census, they have always lived among us. In 1788, soon-to-be New York City Mayor Richard Varick noted, “Vagrants multiply on our Hands to an amazing Degree.” Almost a decade later, the city was forced to build a new four-story almshouse to deal with the growing problem. It’s impossible to calculate homeless statistics through history, but the number has, predictably, fluctuated with the financial tides. The population surged after the American Revolution and Civil War. It grew in the late 19th century, as newly industrialized cities were flooded with workers. And it spiked during the depressions of the 1870s and 1930s. More recently, the deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals in the 1960s and ’70s accounted for a rise among the chronically homeless, and the ’80s recession hit just as entitlement programs were being devalued for the first time. It was a perfect storm, from which we still hadn’t recovered when the financial and mortgage crashes occurred in 2008. In New York, this new crisis meant that stably employed parents could, in an instant, find their family evicted if the landlord went underwater.

Through the years, society has generally responded with mounting charity. A 2007 Public Agenda report noted that 85 percent of New Yorkers approve of spending their tax dollars on housing the homeless—and 62 percent would even pay more. However, for all our do-good instinct, there remains an undercurrent of distrust. Kenneth L. Kusmer, author of Down and Out, On the Road: The Homeless in American History (Oxford University Press), suggests that this could be a legacy of the Puritans. The flip side of a society that values individual industry is that it also tends to be unforgiving of those who cannot or do not work. The 16th-century Calvinist theologian William Perkins warned that “wandering beggars and rogues” should “bee taken as ennemies [sic],” and at our country’s founding, whipping, branding, ear cropping, and stockades were standard practice for curbing homelessness. A New York Times editorial in 1886 called “the tramp” a “victim of a violent dislike to [sic] labor and a violent thirst for rum.”

We’ve come a long way since then, but even in the late 20th century, New York mayors frequently relied on police to “clean up” neighborhoods plagued by “bums.” In 1964, NYU persuaded the local precinct to sweep up the homeless men wandering through campus. And the same 2007 Public Agenda report on New Yorkers’altruism found that three-quarters of residents believe that the homeless lack motivation and are gaming the system for better housing. The truth is that we’ve never quite shaken the suspicion that homeless people may be untrustworthy, lazy, dangerous—and directly to blame for their situation. And so, as a show of trust, we generally demand that they help themselves first, if they want our aid. Ironically, the most effective—and cost-effective—program for the chronically homeless turns this whole notion on its head.

Around the same time that Beth Weitzman was working with homeless families, a young psychologist, Sam Tsemberis (GSAS ’85), was striking out in his attempts to lure mentally ill street dwellers into treatment. It was difficult to sustain a therapeutic conversation with someone preoccupied with where they were going to find lunch that day or bed down that night. “People would often say, ‘I need a place to live,’ ” Tsemberis says. And he would try to oblige them, offering to take them to Bellevue Hospital, where he directed an outreach program. But those beds were just a place to crash, and came with conditions. One of the hallmarks of American charity is that housing should be earned by getting sober, or staying on medication, in the case of those with mental disorders. Pushed to frustration, Tsember is thought: Why not just remove the housing hurdle?

In 1992, Tsemberis founded the nonprofit Pathways to Housing, which provided the mentally disabled homeless with their own private apartments, often in less expensive neighborhoods in the Bronx. The units are usually one-bedrooms or studios, and Pathways “clients,” as they are called, may comprise up to 10 percent of one building’s tenants. Pathways withholds one-third of a client’s monthly disability check—those with diagnosed disorders may receive Social Security income as a result of deinstitutionalization—which goes toward rent. There’s no probationary period, nor is the client required to stay sober, take medication, or even meet with clinicians. There are no urine tests or threats of expulsion. If there’s a problem with the landlord or a neighbor, Pathways intercedes. If the client is thrown in jail or rehab, Pathways holds the apartment for them. If they’re evicted, Pathways finds them a new one.

It worked astoundingly well. A randomized trial, funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, showed that some 88 percent of Pathways clients stayed off the streets during the five-year period studied, compared to just 47 percent in programs that required treatment first. It was as if the client had won the lottery, Tsemberis explains. “ ‘Look at this! This is incredible!’ they think. ‘I’m going to do whatever I can to keep this place,’ ” he says. “So the motivation to deal with the illness or addiction is actually activated after the housing. Nobody thinks of incentives that way.”

Indeed, once housing was removed from the jumble of daily worries, most clients were willing to attend to other problems. A measure of control and security had returned to their lives. In 2004, Deborah Padgett and Victoria Stanhope, both professors at the Silver School of Social Work, led a team of researchers to further compare Pathways to traditional programs. In a $1.4 million qualitative study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, or NIMH, the team found that more than half of those in traditional treatment went AWOL during the course of a year. But only 11 percent of Pathways clients left the program during the same time—and, notably, it was to return to their families. “If you don’t engage people, they leave,” Padgett says. “So the backdrop to this is a really high dropout rate, what’s called the ‘institutional circuit,’ where people go from jail to hospital to shelter, and all of those options are more expensive than an apartment.”

Almost as compelling is that Pathways clients were three times more likely to abstain from heavy drinking or drug use, even though it was never required of them. “That to me was the missing piece,” Padgett says.

Of course, just because someone is finally off the streets, and may even be managing their disorder and staying clean, doesn’t mean all of their troubles go away. The chronically homeless typically live 25 years less than the average American. They’ve often accumulated an array of serious health conditions—HIV, tuberculosis, heart and liver diseases. Some have been physically or sexually abused. And they remain pariahs, which can set up barriers to jobs and friends, and the social wealth they bring. With the support of a new $1.9 million grant, also from NIMH, Padgett and Stanhope are now investigating how the homeless recover from their panoply of problems over time, and what role housing plays in this.

In the mid-2000s, the Pathways model caught the eye of author Malcolm Gladwell, whose New Yorker article provided a “celebrity boost,” in Padgett’s words, to what has become known as the “housing first” (versus “treatment first”) approach. He also eloquently discussed the one hang-up with programs like this: They aren’t fair. “Thousands of people…no doubt live day to day, work two or three jobs, and are eminently deserving of a helping hand—and no one offers them a key to a new apartment,” he writes. But even if it isn’t ideal, housing the chronically homeless is by far the least expensive and the most effective solution. As the protagonist of Gladwell’s story, “Million-Dollar Murray,” careened through public services, he ate tens upon thousands of public dollars. To keep someone in a New York City psychiatric hospital for one year costs $433,000; a state psychiatric hospital is $170,000; jail is $60,000; a shelter is $27,000. It costs only $21,000 a year to give that same person a Pathways apartment. This is about efficiency, Gladwell notes.

Pathways now operates in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Burlington, and similar programs have sprung up across the country, thanks in part to a one-time $35 million infusion from the Bush administration in 2002. The model—and its efficiency—had also caught the eye of Republican Philip Mangano, who ran the Interagency Council on Homelessness from 2002-09 and convinced the Bush administration it was a worthwhile investment.

Efficiency is a favorite word of New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg. And, indeed, his administration has delivered a new order to the Department of Homeless Services by streamlining the shelter application process from days to hours, and creating a preventive program for those at risk of losing their apartments. He also vowed to reduce homelessness by two-thirds.

That never happened. Though there was a slight dip in homeless New Yorkers in 2006, their ranks have climbed steadily. Blame the economy, and years of budget cuts. But also blame how we connect poor people to housing. We simply don’t have enough cheap apartments, or an efficient way to get people into them. As the system works now, only about one-quarter of New Yorkers who need housing assistance get it, says Ingrid Gould Ellen, professor of public policy and urban planning at the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. “It’s this crazy lottery system,” she says, where applicants are randomly chosen for city- and state-subsidized apartments. And if you don’t win, there’s always the city’s eight-year-long waiting list for federal Section 8 housing.

One of the few entries to affordable housing is through a shelter, which, in theory, should operate like an emergency room but more often functions as a long-term care center, where some families wait in limbo for a year or longer for a permanent home.

“The trick or challenge is to house people more cheaply,” says Ellen, who co-directs NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, has been an adviser for HUD, and chaired candidate Barack Obama’s transition team on housing policy from 2007-08. Ellen suggests that communities find new ways to divvy up what they’ve already got: split current subsidies four ways, vary the amounts, enact time limits. We might, she suggests, even loosen building and occupancy codes. Many of these are local regulations, such as requirements that each unit must be a certain size and have a private bathroom, or limit the number of people per square foot, which, as they accumulate, can substantially inflate the cost of housing. Ellen suspects that New Yorkers in particular might reembrace dorm-style buildings, with a bathroom down the hall or a shared kitchen and other communal spaces. “I’m not advocating slums,” she says. “We can live in smaller spaces; we can live more cheaply.”

The question remains which of these innovations, or which balance of them, could empty the shelters. But for the first time in the history of homelessness, we have embarked on a course of action informed by research. Pathways director Tsemberis notes the greatest obstacle now is mustering the political will. As it stands, he says, “We have the solution.”