fiction

A Howl and a Hoot

Maryrose Wood’s novels offer wit and wisdom to young readers

by Amy Rosenberg

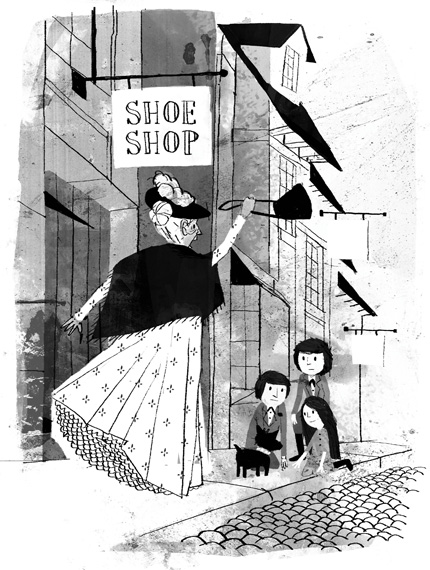

These days, there are few penniless 15-year-olds who leave school to become governesses at extravagant mansions in the English countryside. But there is Penelope Lumley, protagonist of The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place (HarperCollins), a hilarious series of novels for young readers. A Victorian-era orphan who has spent her life at Agatha Swanburne’s Academy for Poor Bright Females, Penelope is told one day by her beloved headmistress that she must leave to make room for another bright girl in need. She finds an appointment at, yes, an extravagant mansion, where the job description calls for, among other skills, a love of animals. When she arrives, she discovers why: Her three new charges have been raised in the woods by wolves. Penelope’s mission is to educate them—after teaching them to speak instead of howl and to wear clothing.

It will come as no surprise that Maryrose Wood (GAL ’96), creator of The Incorrigible Children, was inspired partly by Jane Eyre, her favorite book when she was a child. Like Jane, Penelope must make her way through an oppressive world, drawing on great inner strength to propel herself to security and happiness. But while Jane Eyre attended a school run by sadists who starved their pupils both physically and mentally, Penelope’s strength derives in part from the nurturing aphorisms said to have originated with her alma mater’s founder: “One can board one’s train only after it arrives at the station,” for example; “All books are judged by their covers until they are read”; “There is no alarm clock like embarrassment.” These “Swanburnisms,” as Wood calls them, help to guide Penelope through a series of adventures with the children, and eventually to uncover a great mystery surrounding their origins—and her own as well.

Reading the books (three have been published so far; Wood anticipates six in the series altogether), it’s easy to imagine Wood as something like Agatha Swanburne herself—wise, optimistic, gently authoritative, cheerfully hardworking—and that’s a fairly accurate portrayal. Before writing the Incorrigible series, Wood, 50, wrote seven novels for teenagers, all acclaimed by the major children’s book review publications for their humor and “pitch-perfect narration.” But she came to this career late in life; her first book was published only in 2006. That means that, with the publication of the latest Incorrigible volume, she’ll have written 10 books in six years. “It took me a long time,” she says, “but I finally understood that what I was interested in—critical questions about audience and meaning, and the techniques used to solve narrative problems—was the work of a writer.”

Her first calling was the stage. A Long Island native, Wood had harbored dreams of acting on Broadway since adolescence, and spent much of her teenagehood stealing into the city to see any show she could get last-minute tickets for on the weekends. (Her 2008 book, My Life: The Musical [Delacorte], draws from those experiences.) She enrolled at NYU as an acting major, and before the end of her sophomore year had landed a role in the Stephen Sondheim musical Merrily We Roll Along. It was a “legendary flop,” Wood recalls; nonetheless she dropped out of school in order to devote herself wholly to acting. It took nearly another decade before she realized that she was actually a writer at heart. So she reenrolled at NYU, and four years later, in her mid-thirties and a young mother, she had in hand a BA from the Gallatin School of Individualized Study.

For a while Wood stuck to screenplays and musicals, including The Tutor, which won the Richard Rodgers Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters three years in a row. But when a friend convinced her to compose a novel for teenagers—her highly praised 2006 debut, Sex Kittens and Horn Dawgs Fall in Love (Delacorte)—she felt she’d found her true calling. “Teens and children have very little control over their lives,” she says. “Novels allow them to explore the possibilities of lives totally unlike their own—not so much to escape their situations, but to give them knowledge.” Wood, who now also imparts knowledge to would-be authors by teaching fiction writing at Lehman College in the Bronx, believes in the power of guiding her young audience with literature. “It’s a way of helping to prepare them for the adult world,” she says. “It’s one thing Jane Eyre did for me.”

“Novels allow [children] to explore the possibilities of lives unlike their own—not to escape but to give them knowledge.”