history

The People’s Gift

An historian uncovers lady liberty’s little-known past

by John Bringardner / GSAS ’03

The journey to the top of the Statue of Liberty is like a trip abroad. You need a ticket and an ID, and when you finally make it to your destination—after a boat ride, extensive security checkpoints, and a strenuous hike—everyone speaks a foreign language.

For historian Edward Berenson, director of NYU’s Institute of French Studies, the visit was the rare research mission that didn’t require a passport. In his latest book, The Statue of Liberty: A Transatlantic Story (Yale University Press), Berenson unpacks the largely misunderstood story behind the statue’s French origins, and traces its path as one of America’s most famous symbols.

When the statue was first conceived of in 1865, France had experienced nearly a century of revolution and counterrevolution. In the midst of Napoleon III’s authoritarian regime, a small group of liberal Frenchmen imagined a monument to the United States—which had just emerged from the Civil War a battered but still-united, democratic republic—that would also serve as a rebuke to their own dictatorial government.

By the time the statue was dedicated in 1886, Napoleon III was gone, replaced by the moderate French Third Republic. Lady Liberty quickly settled into her role as an American icon, one whose meaning has continued to shift with the tides of culture and history.

Berenson spoke with NYU Alumni Magazine about the copper colossus, and his own re-education in American history.

Your book is part of the “Icons of America” series, but much of it takes place

beyond our shores.

It’s amazing how little most Americans know about the French history

of the Statue of Liberty. Basically they think it was a gift from France, which it wasn’t.

It was a gift from certain French people to the American people—the governments were not

involved.

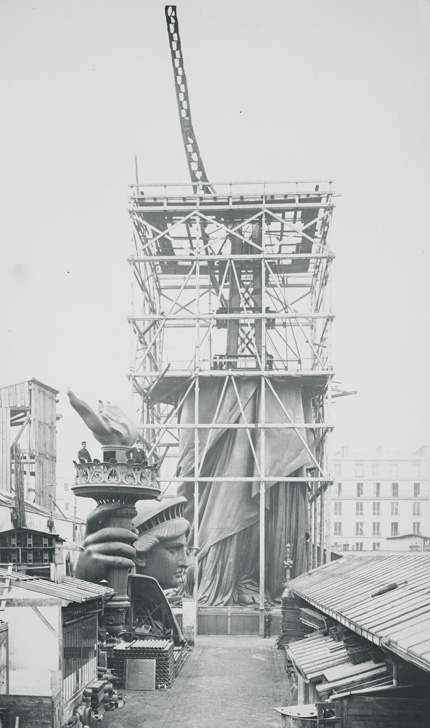

None of the editors I worked with, for example, knew that Gustave Eiffel had built the skeleton. Nobody knew there was an Eiffel tower inside the Statue of Liberty.

Were you familiar with the statue’s history when you took on the project?

I knew a lot about the French iconography, the history of Marianne, [their national] symbol of liberty, and all that kind of thing, so what I had to do in order to write this book was learn about the American side of the story.

What was the American reception like? Had there ever been such a gift from one people to another?

It’s pretty unusual. There were a few skeptics in the U.S. who referred to the statue as a Trojan Horse, but most of the opposition wasn’t that explicit. It was more like: Why should we want this? We don’t have classical Greek and Roman statuary; that’s not who we are as 19th-century Americans. So when [French sculptor Frédéric Auguste] Bartholdi first tried to sell the idea, a lot of Americans were befuddled.

One of the other things I learned is just how decentralized the United States was at the time, and so people from Philadelphia, much less San Francisco, couldn’t possibly see why they should care about a statue that’s going to go up in New York Harbor.

The statue was proposed at the end of the Civil War. Were the French making a specific

statement?

It’s completely fascinating. Emperor Napoleon III wanted the South

to win the Civil War because he wanted to see a weak and divided U.S.—he had designs

on Mexico.

So there’s a whole geopolitical thing, and that’s why it’s really important to specify that it wasn’t a gift from the French government, because that government was pretty hostile to the U.S., and certainly hostile to its democratic values.

What was your research process like?

There was a lot to do. Bartholdi’s wife, who outlived him by a decade, deposited his papers in the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, which is the training institute for technology. It’s mainly a massive archive of press clippings—from French papers and American papers, from German papers—and that was phenomenal. I had free rein, so I could follow the public opinion about it, and then I found all kinds of images.

And one of the things I discovered is that, because of all the drawings of the Statue of Liberty, the illustrated press, [it] was a reality before it even went up—and not just a reality, but a celebrity.

One of the reasons why this foreign import, which didn’t really have any intrinsic meaning here, could get accepted in this country, and then embraced, is because the mass media of the time made the statue so much of a reality that by 1880 or so, most Americans couldn’t imagine not accepting it.

How do you think the book will be received in France?

It has a different meaning, but there’s a real pride that a lot of French people feel about the Statue of Liberty. There are 13 replicas in France, three in Paris and the rest sprinkled around the countryside. Once Bartholdi made the model, it made sense to run off some copies. And the foundry ran off a lot of copies.

Now there’s an entrepreneur who just created another dozen because he was able to make a digital mold from the original plaster model. He’s selling them for more than a million dollars apiece.