environment

The Sustain Game

NYU hits its green goals years ahead of schedule, but is that enough?

by Andrea Crawford

Five years ago, anyone taking a late-night, summertime stroll around NYU would have seen clear evidence of a city that never sleeps. No matter the hour, lights in most university buildings would have been ablaze and had one stepped inside, an icy blast of air-conditioning would have greeted them. Things have changed.

The moment NYU saw the light, as it were, dates to the fall of 2006 when the university launched a formal green initiative. The following spring, it hired Jonah “Cecil” Scheib, as its first director of sustainability and energy, and Jeremy Friedman, as manager of sustainability initiatives, and announced a bold mission. As part of New York City’s PlaNYC 2030, NYU took up the mayor’s challenge and pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 30 percent per square foot by 2017. Last fall—some six years ahead of schedule—NYU kept that promise to the city. “We’ve been enormously aggressive on reducing our energy use,” Scheib says. “I don’t know anyone else who’s cut 30 percent in five years.”

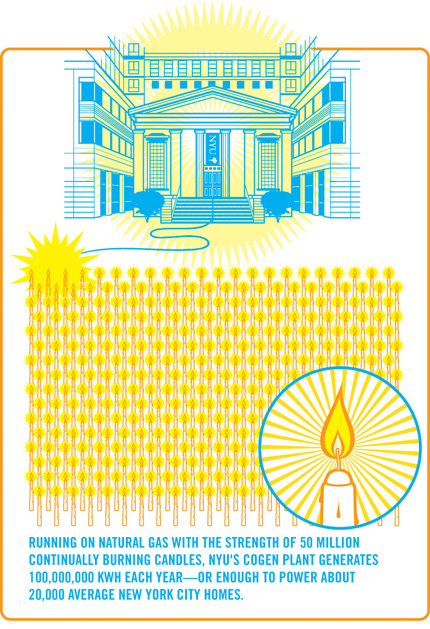

But Scheib and Friedman aren’t ready to accept any accolades on the university’s behalf; there’s plenty of work left to do. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, or the amount of carbon that’s released into the air, can be accomplished in two ways. The first is to use cleaner energy sources—more highly refined oil, natural gas, or renewable sources such as wind, geothermal, and solar power. In fact, to mark the launch of its sustainability initiative, NYU made one of the nation’s largest purchases of wind power in 2006 and ’07. More significant, the university invested $120 million to replace its 30-year-old, oil-fired power plant with a new natural gas-powered co-generation plant. This facility, which went online in 2010, now supplies electricity to 22 campus buildings, while using the steam it generates to supply heat and hot water to another 37.

The second way to lower emissions is to reduce energy usage, and when Scheib arrived at NYU, he was determined to focus first on consumption, and then supply. “There’s no point in putting solar panels on the roof to run a space heater in the summer because people are so cold in their office,” he notes. At first, NYU took the most straightforward steps. “You know how your mom told you to shut off the light when you leave the room?” Scheib asks. “We weren’t doing that.” Scaling heating or cooling and lighting of buildings back to a minimal level from midnight to 6 am, for example, reduces energy consumption by 25 percent. Even shutting it down for just a couple of hours a night still creates sizable cuts.

But turning off the lights also meant breaking electrical wiring apart, so that one out of every few lights in an office or hallway remains lit for safety purposes, or making light switches operable office by office, rather than a whole floor at a time, so janitorial staff can use only the specific light they need. NYU installed new, higher-efficiency lamps and ballasts, which alone can cut lighting loads 40 to 50 percent, and occupancy-based or daylight harvesting sensors, which means office lights grow dimmer when sunlight fills a room.

“It’s been a building-by-building approach to see what we can do,” says Dianne Anderson, manager of sustainable resources, who oversees these efforts. In student residences, for example, she and her staff installed some 4,000 individual “smart thermostats” in an occupancy-based system, which knows to scale back heating or cooling when no one is in a room. Another project involves making data centers, the rooms that store the university’s servers, more efficient because they must be kept very cool to offset the heat they generate. Based on the slew of projects planned, Scheib estimates that within the next three to five years, NYU will have cut energy consumption by 50 percent, a number he says is “not pie in the sky.”

Beyond this, the university is aggressively studying the potential of biofuel mixtures and requesting proposals for renewable energy alternatives. But harvesting such power in the middle of Greenwich Village poses many obstacles. “With tall buildings and skinny roofs and heavy loads all the way down, there’s literally not enough sun input, or wind input, or geothermal inputs to power [these] buildings,” Scheib says. “But it can help.” Also helping are innovations from students, faculty, and staff who have received nearly $400,000 in NYU Green Grants for some 61 original projects since 2007. The aim is to engage the community in devising sustainability efforts—and the program has yielded many now-institutionalized projects, including a campus bike share and an initiative that uses overflow food in dining halls to feed the homeless. Scheib says that NYU embraces the challenge of pursuing clean energy in an urban setting: “If we can do this in Lower Manhattan, we’ve shown that you can do it anywhere.”

This progress has not gone unnoticed. Last year, the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education, or AASHE, gave NYU its highest rating, one of only 23 colleges and universities in the country to receive a “gold” distinction. This system, an independent program called STARS (the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System), considers broad criteria, measuring an institution’s entire educational, cultural, and operational approach to sustainability. In the operations category, NYU ranked highest among all 122 schools assessed. AASHE also presents individual national awards, and last fall its top prize for student research went to Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development graduate student Annie Bezbatchenko for her dissertation on student behavior and sustainability.

Meeting its pledge to New York City so far ahead of schedule will be a significant accomplishment, but Scheib suggests that the philosophy of “cuts” may already be outdated. Instead, he and others are asking new questions: Should the university simply pick an arbitrary number to aim for? Or is there a better way to create new targets? In essence, how much energy does a building actually require? In 2007, President John Sexton signed the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment to reach “climate neutrality”—or net-zero carbon emissions—which NYU estimates it can achieve by 2040; engineering studies are now under way to help make that happen. Scheib says: “Right now we’re driving 80, and I don’t know if the speed limit is 65 or 35.”

Dumpster Detectives

Once a year, Jonah “Cecil” Scheib and the rest of NYU’s sustainability staff can be found roaming campus and snatching trash bags off the sidewalks. They’re not looking for thrown-out treasures, but rather are attempting to “characterize our waste.”

The staff gathers garbage and recycling from a representative sample of NYU buildings and brings them back to the facilities plant, where they tear open the bags, sort and weigh the contents. From this, they have determined that NYU is diverting just above 30 percent of its waste from landfills. The team estimates that another 60 percent of what’s in the trash is actually compostable material. “Only about 10 percent of what we’re actually throwing away needs to go into the landfill,” Scheib explains.

To improve these numbers, NYU has launched composting pilot projects in a few locations, primarily in dining halls and student residences. It recently started a techno-scrap program, and brown bins to collect dead keyboards, CDs, tapes, and other media now stand on nearly every floor. It also plans to investigate composting paper towels from bathrooms, which account for a large amount of waste.

So what was the most significant discovery lurking in the garbage? Perhaps not surprising for denizens of the city that never sleeps: lots and lots of disposable coffee cups. In fact, in some buildings, cups accounted for almost all of the trash.

As a result, students on the green committee at the Leonard N. Stern School of Business are now working with neighborhood coffee providers to lower the price of beverages for customers who bring their own cups—hoping that a financial incentive will wean students, faculty, and staff off disposable ones.

The goal for landfill diversion, which Scheib believes is well within reach, is 90 percent. Once NYU gets to that level, it will be worth looking at the last bit. Then, for example, the sustainability staff might work with the purchasing department and its suppliers, perhaps lobbying a computer manufacturer not to install the one plastic piece in its keyboards that prevent them from being recycled. “But right now,” Scheib says, “there’s no point in fighting that battle when I’m swimming in coffee cups.”

Jonah Scheib projects that within the next three to five years, NYU will have cut energy consumption by 50 percent.