Cutting-Edge Research

business

The Wisdom of Others

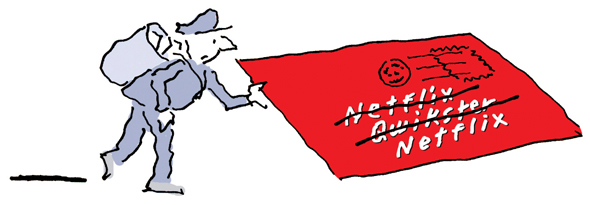

Last September, shortly after introducing a steep price hike, movie-rental giant Netflix unveiled a plan to separate its DVD delivery and online streaming into two distinct services—with two distinct fees. According to a New York Times article published last October, a friend of Netflix CEO Reed Hastings warned him that splitting the services was a terrible idea, but Hastings was undeterred. Customer outrage was so overwhelming that Hastings appeared in a rare video mea culpa and the company scrapped the plan within a month.

This may seem like an unusual incident, but it’s part of a noticeable trend of people in power ignoring advice from others, according to researchers Kelly See and Elizabeth Morrison. The two Leonard N. Stern School of Business professors co-authored a paper that shows powerful people—CEOs, high-level managers, and political figures—are less likely to heed advice from others. Published in the journal Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, the paper combined results from four studies, including one in which researchers asked participants general-knowledge questions (such as estimating the tuition at several universities), and then gave them advice from others before allowing them to submit a final answer.

The study revealed that people in power have higher levels of confidence in their own judgment, and a decreased willingness to incorporate input from others. “Part of what gets you promoted is being knowledgeable and confident,” says See, noting that this trait also has a downside. “Our studies showed that while powerful people were more confident in their judgment than lower-level people, they were also less accurate in their answers.”

This problem extends beyond the workplace, and See believes that our view on leadership needs to change at a societal level. “There’s a general feeling that a good leader is decisive at all times,” she explains. “That’s a wrong theory. A leader doesn’t always need to know the right answer, but they need to know how to find that answer.” In today’s information age, See argues that it’s more valuable for a leader to know where to seek reliable information and honest feedback, and how to synthesize those resources in order to make the best decisions. Her recommendation: “Identify members of your team who don’t agree with you, and promote people who aren’t afraid to challenge you.”

—Sally Lauckner

health care

Righting a Wrong RX

In 1999, a Congressional-sponsored study on U.S. health care turned up some disturbing results: Minority patients are less likely than whites to get organ transplants, to undergo bypass surgery, to receive kidney dialysis, and even to receive heart medication. Further, minorities face financial, geographical, and language barriers preventing them from accessing high-quality care. In response, in 2006, the state of Massachusetts passed a pioneering law attempting to drastically reduce these differences. Through the ambitious “pay-for-performance” initiative—part of the state’s Medicaid program—hospitals that showed a significant reduction in care disparities would become eligible for financial bonuses. Sounded like a win-win.

“They were just wrong about that,” says Jan Blustein, professor of health policy and medicine at the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, who examined hospital records for treatment patterns and spoke to government officials and hospital workers in response to the effort. Her study, published in the journal Health Affairs, revealed little evidence of race-based disparities.

Blustein (WAG ’93) explains that she believes racial disparities do exist, but that they’re quite difficult to pin down. “Legislators made the leap that people were being treated differently in hospitals in ways that could be demonstrated within the program,” she says. But Blustein adds that “the inequities aren’t measurable in a program like this.” Due in part to racial segregation within cities, nonwhite patients receive care from a subset of providers that tend to be of lower quality. Therefore, racial disparities are more likely to occur between different hospitals and not within single institutions as the pay-for-performance model assumed.

Blustein’s study showed that the policy could even end up hurting minority patients. Hospitals that treated a majority of nonwhite patients were penalized under the program because they provided a lower level of care across the board. “We want low-performing hospitals to improve, not to be punished,” she says. One viable solution would be to simply offer additional money to hospitals that most need it, but Blustein warns that this is harder than it sounds. “Politicians may not want to announce more money for hospitals that are doing poorly,” she explains. “[Voters] have this idea that we should reward those that do well. Rewarding hospitals that are struggling, even ones that serve mostly minority patients, is difficult to sell.”

—S.L.

education

Fundamental Questions

New lessons aim to inspire young scientists

Imagine a third-grade classroom in which students spend a full week exploring the origin of knowledge and certainty. They interview one another with questions such as, “What is something you know?” and “How do you prove it?” They analyze texts, identifying claims authors make and the evidence behind them. They pinpoint sources—books, movies, the Internet—and evaluate their validity. “The focus,” explains Susan Kirch, associate professor of science education at the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, “is on giving students the opportunity to learn to use the tools of a scientist.”

Most science curricula in the United States fail to do this, Kirch argues. Instead, they focus on presenting formulaic models that emphasize practical skills. For example, instead of showing kids how to use evidence to support or challenge a given scientific claim, many programs merely teach how to produce a report in the correct format. Instead of conveying the algorithms that underlie math problems, many lessons merely demonstrate how to “do” problems. No one is arguing that practical skills aren’t useful or necessary, but, Kirch says, “students have to understand the tool they’re using before they begin using it.”

With this in mind, Kirch and her colleagues at NYU’s STEME Education and Research Center, a new facility devoted to understanding how teachers learn to impart these subjects and how children grasp them, are seeking new ways of teaching science to young children.

Along with her co-principal investigators, Kirch has secured nearly $450,000 from the National Science Foundation for an initiative called the Scientific Thinker Project. The curriculum is based on the idea that evidence is a fundamental scientific tool and that children have the capacity to understand its nature—what it is, where it comes from, how to evaluate it.

Pamela Fraser-Abder, associate professor of science education at Steinhardt, also recently won a three-year, $2.1 million grant from the New York State Education Department, which funds a pilot program aimed at integrating new science teachers more deeply into the communities they serve and improving retention rates among them. “Gradually,” Fraser-Abder says, “participants take on greater responsibilities for teaching, so that by the end of a school year, they have gained solid practice. They are more likely to remain in the science education field because they become more invested in the work.”

There is often talk in this country of a crisis in science education. But, Kirch says, while American students may perform dismally on international standard exams, or avoid career paths in STEME fields altogether, the real problem is that, from the earliest years of schooling, curricula fail to instill a true understanding of how to think scientifically. While it’s not clear whether great science lessons translate into more biologists and engineers, the goal for now, Kirch says, is to help children realize “the scientific way of living is exciting, fun, and rewarding.” Once that happens, she hopes more students may just be inspired to explore a career in science.

—Amy Rosenberg