Americana

This Music Is Your Music

Nora Guthrie resurrects her folk-legend father for a new generation of listeners

by David McKay Wilson

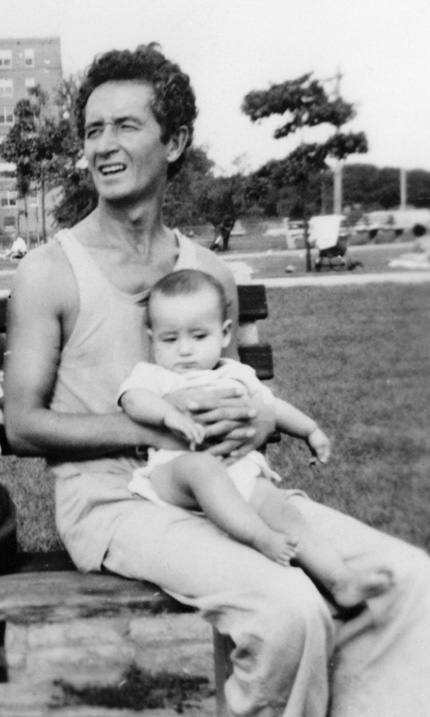

On Sundays as a child, Nora Guthrie (TSOA ’71) would often sit in the corner of her parents’ bedroom and marvel at the likes of Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger standing just a few feet away. Such stars would regularly trek to her family’s modest Howard Beach, Queens, home to visit with her dad, Woody, the father of American folk music. By then, Huntington’s disease—a progressive neurological disorder—had sapped his body and mind, but the well-wishers still gushed to him about their latest works and played his songs. “Dylan was the greatest,” recalls Nora, now 62. “He became the Woody jukebox. He wanted to go out into the world to serve him.”

More than three decades later, in 1994, Nora would also serve her father’s legacy by co-founding the Woody Guthrie Archives. And this year, she is helping to orchestrate the 2012 centennial of his birth, for which the archives has partnered with the Grammy Museum to put on festivals in both Berlin and Woody’s hometown of Okemah, Oklahoma, as well as a Kennedy Center gala in Washington, D.C. The anniversary will also herald the release of seven books and five CDs, including Note of Hope: A Celebration of Woody Guthrie, co-produced by Nora and bassist Rob Wasserman, and featuring Jackson Browne, Ani DiFranco, Lou Reed, and Studs Terkel, among others, who perform Woody’s lyrics in spoken prose, hip-hop, traditional acoustic folk, and rock ’n’ roll. The album illuminates Woody’s thoughts from New York during his final decades, offering views of the harsh life led by those on society’s margins, and the many joys of falling in love.

Dubbed the “Dust Bowl Troubadour” for his baleful paeans to the Oklahoma migrants of the 1930s, Woody Guthrie, who died in 1967, composed more than 3,000 songs—including the anthem “This Land Is Your Land.” His oeuvre ranges from traditional folk tunes to political ballads, from rambling blues to children’s ditties, and many are now archived in the Library of Congress. His spirit emboldened the music and activism of the early beatniks and youth in the 1950s and ’60s, and continues to inspire today’s artists, including the bands Wilco and the Indigo Girls, and rock legend Bruce Springsteen. Rage Against the Machine guitarist Tom Morello sang “This Land” at an Occupy Wall Street rally last October, and a year earlier, he recorded Woody’s “Deportee” as a protest against Arizona’s anti-immigrant law.

But to Nora, he was always, simply, “Dad.” She never actually knew the legendary Woody—the ever-vigilant artist with a passion for justice. His health and mental state continued to deteriorate throughout her childhood. And once the family could no longer care for him at home, Nora’s mother, Marjorie, would drive her and her brothers, Arlo and Joady, to visit their father at Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in Morristown, New Jersey. “Growing up with my dad was the hardest thing in my life,” says Nora, who also serves as president of Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc. “We’d visit him at the hospital, which was like a scene out of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. His clothes were dirty. He couldn’t control his bladder. He couldn’t walk. He could barely get a fork to his mouth.”

It was, in part, through founding the Guthrie Archives and becoming the curator of his words and music that Nora was finally able to grow closer to him. “Every aspect of his creative legacy evoked something different in me,” explains Nora, who this May will release My Name Is New York: Ramblin’ Around Woody Guthrie’s Town—A Walking Guide, authored by her and with archival material about the 27 years Woody lived in the Big Apple. It will include an audio CD of song clips, lyrics, and original interviews to accompany those who take the suggested walking tour. The Guthrie Archives will also soon relocate from her home in Mount Kisco, New York, to Tulsa, Oklahoma, to a facility created by the George Kaiser Family Foundation, which purchased the collection from Guthrie Publications for $3 million in December 2011. Nora, who had long sought a permanent home for the archives, will continue to license her father’s songs and recruit artists to record them.

Cultivating Woody’s legacy, however, wasn’t always Nora’s priority. With her DNA, it seemed inevitable that she would become an artist. Like her mother, who performed with the Martha Graham Dance Company, Nora fell in love with dance and studied it in the late ’60s at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. Those were heady days in New York, as modern dance blossomed around Greenwich Village, and she collaborated with director Robert Wilson, interned with lighting designer Jennifer Tipton, and performed with Meredith Monk in political street theater. She and classmate Ted Rotante (TSOA ’71) formed Guthrie-Rotante Dance Company, which flourished. They soon married and toured nationally with the company.

In the early 1980s, Nora put performing aside to raise her children, Cole, 25, and Anna, 33, who works as director of events and programs for Guthrie Publications, which does outreach in schools, and has conferences planned at four universities, including Brooklyn College and Penn State, in 2012. But by 1992, Nora had found her way back into show business, helping Harold Leventhal manage her father’s catalog of songs. In 1998, she was executive producer of Billy Bragg and Wilco’s Mermaid Avenue (named for the street Woody lived on in Coney Island). The punk rock interpretation of his music was not welcomed by all quarters. “It was considered blasphemy by some because it wasn’t folk,” Nora recalls, “but we got a Grammy nomination and great reviews. It gave me the courage to keep going.” A decade later she won a Grammy, as producer of The Live Wire: Woody Guthrie in Performance 1949.

Following this success, Nora has continued stretching her father’s appeal. Her maternal grandmother, the well-known Yiddish poet Aliza Greenblatt, lived across the street from the Guthries in the 1940s and became close with her son-in-law, as the two would often discuss each other’s work while sharing their common interests in culture and social justice. Woody was taken with Greenblatt’s heritage, which prompted him to write a number of Jewish-themed lyrics at the time. Upon discovering these songs, Nora asked the Klezmatics, a Jewish Klezmer band, to set them to music, and they soon recorded the critically acclaimed Woody Guthrie’s Happy Joyous Hanukkah, as well as Wonder Wheel: Lyrics by Woody Guthrie, which won a Grammy for Best Contemporary World Music Album in 2006. But the latest CD, Note of Hope, is perhaps the most personal for Nora because it offers insight into Woody’s last lucid and productive years. “His ideas from the heart never get old,” she says. “And his philosophy, his truths, are made accessible through music.”